PART 1

Introduction

Chittaranjan Naik reminds one of the Vamana Avatara of Sri Vishnu. He is an unusual genius who strides the three huge worlds of modern science, Indian traditional philosophy, and Western philosophy with aplomb. The graduate and post-graduate degrees in Aeronautical Engineering and Industrial Engineering respectively from IIT-Madras followed by a career as a technocrat in various organizations gives him more than adequate scientific authority. He resigned from his job and devoted himself full-time to the study of both Indian traditional and Western philosophies for more than a decade, which again should give him some authority.

He shows in this book, like in his previous book Natural Realism and Contact Theory of Perception, how lucid has been the development of the theme of the Self or Consciousness in Indian darshanas or philosophies. The understanding of reality and consciousness has been in clear terms for thousands of years and it is an unfortunate fallacy of our educational systems that most of us are not even remotely aware of it. It is a tragedy that an average Indian who wants to explore philosophy would pick up a Bertrand Russell or a Will Durant. Not to take away anything from them, but nobody even thinks or knows about books by Ramakrishna Puligandla or Hiriyanna on Indian philosophy.

Consciousness has been the trickiest problem in philosophy. Western philosophers and neuroscientists continuously indulge in never-ending discussions and debates on consciousness. Indian philosophy has taken a uniform stand on consciousness without change for centuries, much before even Greek philosophy (Western philosophy appropriates itself as heirs to the latter). The most crucial difference between Western and Indian philosophy has been the importance of the study of philosophy. For the former, philosophy is still mostly a dry intellectual exercise lying somewhere between where religion ends and science begins. The tool of logic also gives importance to the form of arguments (syntax) irrespective of whether they explain the reality or not, rather than the meaning of arguments (semantics).

Indian philosophy does not work with such artificial paradigms. It is never a dry intellectual exercise and has a deep purpose of not only explaining reality but also as a major tool in personal liberation or moksha, the foremost Purushartha. In the first book, which is perhaps a necessary background to this book- though not mandatory, Naik explains the perception of the reality around us through the idea of the Self-existent in Indian traditions. However, the author incorporates the relevant aspects of the first book into this second book where he proves the existence of the Self. It is a paradox, Naik says, that scientific progress and the inability to question scientific ideas prevents the understanding of reality in western traditions.

What follows is a four-part summary of Chittaranjan Naik’s book, On the Existence of the Self, with the permission of the author himself. The book broadly divides into two parts. In the first part, Naik proves the existence of the self by demonstrating that goal-oriented actions emanate from a unique power of the self (also known as kriya shakti). This power is from beyond the laws of physics and thus Naik dismantles the idea that the physical universe forms a causal closure (a strict cause and effect working purely at a physical level).

In the second part, he shows how mistaken their reasonings were for the influential western philosophers like Hume and Kant who buried the idea of the soul in western traditions. Similarly, Naik shows how Socratic and Descartes’ dualism are more in line with Indian traditional philosophy. The rejection of Cartesian dualism led to increasing confusion in western philosophy continuing till date, says Naik. The summary does not replace the book. It only provides the salient features of the book so that reader may have a better understanding while reading the book itself. The fantastic book needs careful reading and it is a promise that the reader will confront many striking and illuminating ideas at regular intervals throughout the book. The language is surprisingly easy for a layperson and this makes it more interesting.

The Self (consciousness) and its powers

In contemporary philosophy, the overwhelming belief is that consciousness (or awareness) does not have the power to cause anything. It is the subjective texture of experience leftover after the provision of all functional explanations. For most philosophers, consciousness is a secondary outcome or emerges as an epiphenomenon of physical matter. Even the few like David Chalmers who attribute a primary nature to consciousness agree that the latter has no functional role. Indian traditional philosophy challenges this view which not only ascribes a primary nature to consciousness but also to its causal power over certain aspects of reality.

Socrates and Plato held the belief, like Indian traditions, of a distinct indestructible and eternal soul separate from the destructible matter. However presently, the conception of self, being an emergent property of matter, disappear at death. Western philosophy treats the ‘self’, ‘soul’, ‘consciousness’, and ‘mind’ as the same arising from some part in the brain. The indiscriminate mixing of categories leads to muddling up many issues in philosophy especially the mind-matter problem. Does the mind give rise to matter or does matter give rise to the mind?

Indian philosophy makes a clear distinction between the self and mind-matter as two distinct identities. Mind and matter belong to the same category. In Indian traditions, the category of the cognizer is the self (or Purusha) whose characteristic feature is consciousness. Hence, self, consciousness, cognizer, and Purusha belong to the same category of sentience. Mind-matter, also known as prakriti and always insentient (inert or having jadatva), are one only belonging to the distinct category of the cognized.

The self, as the cognizer, can never be cognized as an object. However, the self is either known by its reflection on the cognized objects (like the hidden sun inferred from the light reflecting on the moon) or most importantly, by its self-luminous nature. A robot, Artificial Intelligence, or a computer also knows, sees, listens, or converses with a living or non-living object. But additionally, we also know that we know the object. I am seeing something but I also know that I am seeing something. This is the self-luminosity of the cognizer.

In the Western tradition, the power assigned to the soul (or the mind) is the power of thinking and reasoning which strictly stays within the ambit of cause and effect arising from matter. However, in Indian traditions, the self has three powers and effects independent of matter and physical laws of cause and effect:

- Iccha shakti (the power of willing)

- Jnana shakti (the power of knowing)

- Kriya shakti (the power of acting)

The exercise of these powers would not reflect in the unmoving and immutable self. They reflect in the mind and the inner instruments of the self while inhabiting the physical body as a being-in-the-world. The self exercises these powers by its mere presence and not by any exertion. It is an unmoved mover.

Iccha shakti is the power of exhibiting a desire for something. Jnana shakti is the consciousness about an object itself that becomes the knowledge about that object. In Indian philosophy, there is no fundamental difference between consciousness and knowledge. Consciousness is responsible for both immediate knowledge arising from direct perception and inferential knowledge arising in a mental mode as an ideated object.

Finally, Kriya shakti is the power by which the soul (or the self) can act upon external matter. The unimpeded self can act on all matter but the embodied self can only act on certain domains of the physical matter like the motor organs of the body it inhabits. It can act on other matters of the world only by channelizing its motor organs to act. All living beings having the soul possess these three characteristics in varying degrees.

THE PROOF FROM JNANA SHAKTI

Western Traditions in Explaining Reality and Perception

Any attempt to explain perception through a set of purely physical processes fails. When it comes to perceiving objects in the external world, the standard Western paradigm is that light falls on an object first. This reflected light enters the eyes, falls onto the retina from where neural impulses travel via the nerves to a region of the brain. The reconstruction of the image leads to ‘seeing’ the object. The same is true for all the other senses.

This is the ‘stimulus-response theory of perception’- a stimulus evoking a response inside our brains through an intermediate causal chain. Of course, there is a difficulty in explaining how an internal image projects to the outside world. Since the external world is the interpretation in our brains depending on our endowed senses, the reality is indirect- a Representationalism. This contemporary scientific view, forming the basis of both philosophy and neuroscience, gets the term ‘Scientific Realism’ or ‘Indirect Realism’.

The real world (noumenon) is always beyond our capacity of comprehension. The ‘phenomenon’ is always a construction by the senses of the real world. The stimulus-response system is incoherent in explaining the ontological status or reality of the world. If there is an unknown ‘noumenon’ and a representative ‘phenomenon’, then every object in the causal chain from the external world to the perceiver, including the intervening medium is unknowable. Even the brain has a noumenon and it is a representation of something else. What are the true status of our body and the sense organs? This logical extension of the current thinking leads to various conundrums and inconsistencies. The main problem with the stimulus-response theory of perception is the problem of consciousness. It is impossible to perceive an object without there being consciousness of the object. Assuming a stimulus-response model of perception, consciousness would logically belong to noumena which we can never know. Hence, the conundrum is knowing unknowable objects by an unknowable subject too.

There have been some attempts to develop a Direct Realism theory in western traditions saying that there is somehow no transformation by the intervening medium. However, these positions do not reject the scientific principle of reflected light on matter reaching our senses and the brain converting the neural data. Problematically, this scientific paradigm is perfectly incompatible with Direct Realism. One either rejects science or rejects Direct realism finally in the western philosophical traditions.

Reality and Perception in Indian Traditions

In contrast, Indian philosophy stands on a robust ‘Natural Realism’ (or ‘Direct Realism’). The perceiver goes out and reaches the object in the world. This is the ‘contact-theory of perception’. Contact with the object gives direct information of the world as it exists. Hence, the external world as seen or heard is an actual world in its reality and not a construction. This establishes the role of pratyaksha or direct perception as a valid pramaana (means of knowledge). Perception obviously is not a valid source of knowledge in western traditions.

In the Indian tradition, the cognizer (purusha) and the cognized (prakriti) belong to two distinct categories with essential characteristics of sentience (awareness or chaitanya) and insentience (inertness or jadatva) respectively. The sentient self is the cognizer; the inert mind-matter is the cognized. Mind and matter are the two different modes of cognitive presentations (mind-matter equivalence) in which objects appear and reveal the furniture of objective reality. An idea in the mind is the same as the body apprehended in the world of matter. In Indian traditions, a conceived object cannot be unknowable; and if it is unknowable, there is no conceiving.

The self or consciousness is self-effulgent but the absence of ubiquitous perception indicates some primal covering over the self, obstructing its natural revealing power. This obstruction is the three-layered body: mula-sharira (seed-body), sukshuma-sharira (subtle-body), and sthula-sharira (gross body). The most primal covering layer is the nature of sleep. The middle layer is the layer of ideation, the realm of mind. The outermost layer is the layer of the gross physical body through which the embodied-self comes as a being in the world.

The instruments of perception are in this three-fold embodiment. Even though the self has the capacity to reveal objects by its intrinsic effulgence, maya obstructs its power of revealing. A clearing appears in the innermost covering of maya; the middle layer actively reaches out to the object helped by the instruments of perception; and the outermost layer comprising the physical body is the seat of experience. Perception, direct and immediate, is an inside to outside process.

The Embodiments, Reincarnation, and Liberation (Moksha)

The paradox is that the embodiment of the Self does not, in truth, exist which comes not through a physical process but through a cognitive condition whereby the Self morphs as the body and erroneously believes the body to be the self. By its true nature, the Self (with a capital ‘S’), being all-pervasive, has no containment. Only an erroneous cognition generates a certain psycho-physical bodily structure. Self’s embodiment through a cognitive condition forms a core tenet in all the six systems of Indian philosophy with slight variations.

Even when the physical body undergoes destruction, the idea of the body persists in the realm of the mind. The self, still equipped with the power of thinking, considering the body destruction as a loss, craves for a body. In the Indian tradition, this craving, along with the law of causation related to the embodied self’s moral actions in its past births, results in reincarnation of the self in another body.

Embodiment persists so long as the erroneous cognitive condition persists; hence, right-knowledge confers liberation. Thus, when the erroneous cognition dispels, one is set free from the shackles of bondage (to the body) and to the cycles of birth and death. This is the idea of embodiment and liberation that is central to the Indian tradition.

Perception

Perception is by the removal of the covering of maya (avidya or nescience) over the individual self (with a small ‘s’), allowing the conscious light of the Self to reveal external objects. The mind, in a process called vrtti, assumes the form of the target object during a conceptual act. The mind forms a vrtti both when it mentally constructs an object or when it contacts an external object to assume its form. Perception is thus a composite process in which the Self, the mind, and the sense organs together establish a contact with the object.

In the Indian theory of perception, there is no transformation of the object. Once the mind and sense organs contact the object and assume the form of the object by forming a vrtti, there would be a conjunction of the mind, the sense organ, and the object at the very location of the object. There would be nothing in between the self and the object to hinder revealing the object in its true form. Perception is direct and reveals the object in its actual form. Contact is instantaneous since the all-pervasive consciousness that appears within the body is the same consciousness that exists everywhere. Hence, perception is nothing more than the removal of the covering of maya over the individual consciousness to reveal the conjunction that already exists with the object.

The Time-Lag Objection and The Simultaneity Experiment

Light travels at a finite velocity, and so there is always some time interval between the reflection or emission of light from a physical object and the light’s reaching our eyes. When the light of a star reaches our eyes, the star may no longer exist. Hence, Direct Realism is false say the objectors. Naik says that all the premises are theory-laden with the assumptions of the theoretical framework of science: (i) light travels with respect to a sentient observer, and (ii) we perceive objects because of a stimulus-response process.

The time lags observed are the time intervals for light to travel from one observed object- the source of light, to another observed object, namely the object illuminated. It is not for light to travel from the object to the observer. Naik offers an ingenious experiment called the ‘Simultaneity Experiment’ to address the major objection of time lag against direct perception. The author explains the mathematics of the experiment in detail.

Briefly, the measurement of the speed of light has always been from the source of light to another object, but never from the source of light to the sentient observer. A sentient observer would observe the light instantaneously. A nuclear explosion at 44,000 miles or so from Earth; instruments for measuring the speed of light from the event to a space station above Earth; and sentient observers recording the event on their watches on the same station are the paraphernalia for the experiment. If the Indian thinking is correct, the sentient observer would detect the nuclear explosion much earlier than the instruments. Such instantaneous perception of the explosion would be inexplicable through the laws of physics. This is a challenge for any future experiments which can change the present scientific-philosophical paradigms.

Irrespective of whether the Simultaneity Experiment is feasible or not, it would be unreasonable to continue to accept the physicalist theory of perception with all its logical inconsistencies. Thus, the primary cause of perception is not something that belongs to the domain of physical objects (the kshetra). The kshetra and the kshetrajna (consciousness or the conscious percipient) are two separate and distinct components of reality with the latter possessing as part of its nature the power of illuminating objects. If there should be some aspect of reality that defies explanation when considered through purely physical causes and admits to a coherent explanation by the acceptance of consciousness as a separate entity, then it is reasonable to hold that consciousness exists as a substance distinct from material bodies.

In Part 2 of this essay, we see Naik’s proof for the existence of Self through its power of Kriya Shakti.

PART 2

In the previous part, the author shows how perception is a valid and the most important pramaana for gaining knowledge in Indian traditions. He suggests an experiment to show that perception is instantaneous and that such instantaneousness of perception is not explicable without the self. In the present part, Naik presents his proof for the existence of the Self from its Kriya Shakti using probabilities, correlations, and causations.

THE EXISTENCE OF THE SELF – THE PROOF FROM KRIYA SHAKTI

The Evidence Is Ubiquitous

The prior existence of consciousness is necessary for the universe to make its presence known to us. Kriya shakti is the power of consciousness that can cause movement and effect changes in physical bodies. This power is ubiquitous and we are all familiar with it. It is the power we exercise when we move to do anything or to speak. In materialism, this power has its source in the mechanisms of the physical body and the brain. Indian traditions ascribe this power to an intangible incorporeal substance existing within the body.

Socrates was one of the few Western philosophers who recognized the presence of this power in living beings. Physicalists tend to dismiss both free-will and any substance (soul or mind) exercising this free will over physical objects. Physicalism entails that the objects we perceive are all subjective phenomena, a kind of virtual reality as it were, and not real physical objects. However, the physicalist account of perception brings into question the very existence of physical objects.

In Indian philosophy, the perceived world is the real world. Even for Advaita Vedanta with a provisional acceptance of such realism, the perceived world is still the real world. It is not some imperceptible world existing beyond the limits of speech and cognition as held by Indirect Realists. Indian philosophy considers knowability and nameability to be the common characteristics of all objects. A world that can be neither cognized nor referred to by language is an incongruity.

‘Order’ and Verifiability Criteria

In thermodynamics, the terms ‘order’ and ’disorder’ are closely related to entropy which is a measure of the thermal energy in a system that is unavailable for doing useful work. All physical processes within a closed system involve an increase in entropy or decrease in order; this is an inviolable law of physics.

According to some people, entropy can decrease in pockets, apparently defying the second law, but is extremely unlikely (like the odds of shaking the parts of a watch and have them fall into place as a working timepiece). Evolutionists attempt to show how ordered complexity can indeed arise from natural phenomena over long periods of time, occurring one small step after another. However, whether a clock comes into existence or disintegrates, the thermodynamic entropy of the system always increases. Even in evolution, the thermodynamic law of entropy stays intact. Obviously, scholars confuse the notions of entropy and order as defined in thermodynamics with the common sense notion of order.

The author looks at the phenomenon of ‘order’ as a change in spatial dispersions of matter from an initial chaotic (or random) state to a final state of a spatially ordered configuration. This creates a sense of order in our minds. The author comes with the strong hypothesis that order of this kind would never come about through the operations of physical laws alone. This ‘order’ has nothing to do with thermodynamic entropy or thermodynamic order. People arguing against physicalism have rather thoughtlessly used thermodynamic terms and weakened their own cases, says the author.

There are many million instances of such ordered complexity every second arising from disordered dispersals of matter. Brand new cars, clocks, beehives, microchips, aircraft, and giant buildings come into existence all over the planet every second. Order comes out of disorder on a regular basis, yet we fail to notice it amazingly. In all the examples above, there is one thing common: the creation of order out of disorder springs from the presence of living beings. Clearly, life tends to disrupt the operations of the physical universe.

Any hypothesis in Indian traditions needs verifiability for acceptance (unlike the falsifiability criterion of science). The verification criterion that the author chooses to employ uses difference in probabilities between the following two cases:

- Case 1: The probability of the creation of an ordered spatial configuration when they are subject purely to physical laws.

- Case 2: The probability of the creation of an ordered spatial configuration when there is the intervention of living beings.

If there should be a significant difference between the probabilities in the two cases, we may infer that the intervention of living beings introduces into the system something over and above the operation of the physical laws. Living beings consist of an extra-corporeal element possessing the power to act upon and influence the spatial configurations of physical bodies.

The Proof

Obviously, in real-life situations, it would hardly be possible to formulate the probability functions for evaluating the exact probabilities in the two cases due to the great number of variables, events and possibilities involved in them. Unlike a simple case like the tossing of a coin, in cases like assembling a clock or an aeroplane, there are thousands of components each of which would give rise to an event space comprising almost infinite possibilities in terms of their locations and their attitudinal orientations in space.

Fortunately, it is not necessary to evaluate the exact values of the probabilities; it is enough for us to show that the probability would invariably be tending towards zero in one case and to a value tending towards one in the other case. The author then derives the probabilities using an idealized situation. Briefly, if m and n represent the outcome of a component in terms of its spatial location and attitudinal orientation respectively and k represents the number of components, the author derives the probability of a product by random mixing of the parts, without any human intervention, as:

[(1/m) x (1/n)] k-1

As a vivid example, if one divides the space within the boundaries of the system into 1000 spatial locations and 1000 attitudinal orientations and if the number of components is 100, then the probability of the product to arise would be:

[(1/1000) x (1/1000)]100-1 = [(1/10)6]99 = (1/10)105

The probability value is a decimal point followed by a hundred and five zeroes and a one- a very small number. In a real-life situation, the probability value would be much lower than this number because there would be no ready-made component parts and we would have to compute the probabilities of each of the components arising through nothing more than the operations of the natural laws alone. That alone would be very insignificant numbers. Not surprising that the real-life probability would be such a small number that it may take millions or billions of years for the product to fall in place. The probability thus tends to zero in Case 1 scenario- creation of an ordered spatial configuration of matter from random dispersions of the matter when subject purely to the physical laws.

But now consider what would happen if a human being possessed with an intent to assemble the product were to enter the scene. All the components would suddenly, and magically as it were, obtain 100% biases to be in the exact spatial locations and exact attitudinal orientations as required for them to fall into place as a working product. In other words, the probability of the product production will be 1 or, making some allowance for human error, we may say that it will tend to be 1.

When matter is subject purely to physical laws, the probability of the material parts coming together in some ordered configuration tends to zero. But in the presence of human intent, suddenly the probability of the material parts coalescing into some ordered configuration begins to approach the value 1. Thus, one will have to presuppose the presence of some extra-corporeal entity acting in a goal-directed manner to explain the kind of outcome that obtains in this case; and it is the presence of human beings that brings about such an outcome. Thus, the human being cannot be merely an aggregate of the physical bodily parts but also consists of an incorporeal (intangible) substance possessing the capacity for intentional action.

What Does This Proof Achieve?

Everybody knows that the probability of clocks arising by chance is very low and that when human beings with the intent to create them enter the scene these artefacts do come into existence. What does mathematical proof of a common sense event try to achieve?

Firstly, the mere fact that the phenomena in the arguments are commonplace does not make the reasoning faulty. Some of the most famous discoveries of science (like gravity) were by recognizing the most commonplace phenomena staring at us all along. Similarly, we are looking at a power of the self, or of intentional action, right in its face and are not recognizing it.

Secondly, in presenting this proof, there is the setting up of a verifiability criterion by which the truth of the proposition can become verifiable. Indian philosophy stresses on verifiability criteria and not falsifiability for validity. Thirdly, the proof is the establishment of a correlation between the presence of intention and the outcomes of ordered dispersions of matter happening repeatedly, millions of times every year, in the form of the production of cars, beehives, microchips, aeroplanes, buildings and a million more things. In each case, there is the presence of intention and actions directed towards the material components which acquire 100% biases to be in exactly the required spaces and the required orientations to fall in place. There is a case to establish a definite causal connection between the intention and the results of ordered configurations of matter.

This correlation, or vyapti in Indian logic, enables one to infer the presence of the soul from the presence of goal-oriented actions. For, where there is an intentional action, there is always a soul present as the source. Yet, in contemporary discourse, intention does not have the pride of place as an ontological principle. It simply is a manifestation of some underlying physical state in the brain or body. The ‘explaining away’ is not through a logical elucidation but by asserting a dogma.

The dogma lulls the mind into thinking that the phenomenon cited for the inference of the self is a mere appearance leaving the reader confused regarding the nature of the proof. Thus, it is imperative to undertake a philosophical investigation of the belief that goal-oriented actions are nothing more than manifestations of underlying physical processes and show it to be a mere dogma. This refutation of the dogma forms the second part of the proof for the establishment of the existence of the self.

Refutation of The Dogmas: Inexplicability from Physical Causes

The author considers four major objections to his thesis that proceed from the dogma and show them as unsustainable.

Objection 1: Intentional Action Is A Result of The Body Mechanism

The objection states that human intention, or intention in living beings in general, is a phenomenal appearance of underlying physical states or processes in the body. The author says that this is merely the proposition itself posturing to be an argument. It simply is the overarching assumption of physicalism, namely that natural or physical causes alone can explain all things, disguised as an argument. This proposition needs proof as being universally true and not on a hope that things will work out in favour of the proposition at some future time. Science is yet to account for the outcome of life through physical processes.

All the various phenomena for which science has been able to offer satisfactory explanations so far are phenomena that belong wholly to the domain of the perceptible world (kshetra). One can justify extrapolation for other yet-to-be-explained phenomena in this domain. However, the phenomenon of goal-oriented actions proceeding from living beings is not in the domain of the kshetra. The extrapolation becomes unjustified and unwarranted when it defines the relationship between the two different domains- kshetra and the kshetrajna (the field and the perceiver of the field).

The scientific theory of perception and the modern investigation into the nature of consciousness has many inconsistencies and logical conundrums. It is a known fact that aspects of reality pertaining to the relation between the observed and the observer are exclusions to the general rule. In which case, how can we use the general rule to derive conclusions about those that are exclusions to the general rule? One can thus ignore or discard the conclusion derived from the extrapolation, namely that science will one day be able to explain the goal-oriented actions of living beings solely through the mechanics of physical causes.

The purely physicalist explanation for certain aspects of reality, such as the phenomenal texture of experience, the possibility of perceiving the external objects of the world, the presence of goal-directed actions in living beings, have met with limited success. But the conceptions of soul, mind, and matter as held in the Indian philosophical tradition removes many difficulties and harmonizes the relationships between these entities. In contemporary culture, it is not reason but a hegemonic approach that dictates the way. The great successes of the physical sciences have given these sciences an authority that is paradoxically coming in the way of understanding reality.

Objection 2: The Actions Performed by Computer-Controlled Machines Disprove That Goal-Oriented Actions Require the Presence of a Soul

Even computers, or more specifically computer-controlled machines such as robots, should possess souls since they too exhibit such goal-oriented actions. If we deny souls for them, we should logically deny the presence of a soul in human beings too merely on the yardstick of goal-oriented behaviour. Naik says that the fault lies with the way the opponent has understood the invariable concomitance relationship.

When goal-oriented actions point to the presence of a soul, it does not imply that the soul should be present in the immediate vicinity of the goal-oriented actions nor does it mean that the soul should be present within the object exhibiting the goal-oriented actions. The goal-oriented actions have their origin in an incorporeal soul and not in a material thing. All the goal-oriented actions these machines perform have their source and origin in human beings. It is not really the computer or the computer-controlled machine that imparts goal-orientation to the actions exhibited; human beings alone impart the goal-orientation to the machine. Yet, what is it that provides philosophers and scientists with the ground to maintain such a brazen denial of a soul? It is only through certain dogma that has gained enormous currency in the contemporary world.

Objection 3: It Is Possible for All Kinds of Objects to Get Created by Accident

The physicalist now comes up with his prized argument. It is solely the physical constitution and configuration that provides a machine to perform these goal-oriented actions. Just like any configuration, the human body too can come into existence by accident even though the probability of such an occurrence may be extremely low. Such an event would mark the beginning of a new epoch; for the human being that comes into existence would be a self-replicating being, entirely physical and soul-less, but goal-oriented. Thus: a) a purely physical being can be a source of goal-oriented actions and, b) all kinds of things, including inanimate things like clocks and animate things like human beings, can come into existence purely by accidents of nature.

These two influential ideas are nothing more than products of flawed and unsound reasoning which believes that like machines, goal-oriented actions of human beings should also be a property of the physical human body alone. The basic flaw in the reasoning adopted by the physicalist is the conflation of the capacity for performing goal-oriented actions for being a source of goal-oriented actions. The originator of the goal-oriented actions is the human being alone.

The legitimate conclusion is that the physical human body can perform goal-oriented actions just as a computer-controlled machine does, but the conclusion cannot overstep its legitimate limit and conclude that the physical human body can thus be the source or originator of these goal-oriented actions. A human being must possess something over and above the physical body – an extra-corporeal element or soul – by which it obtains the capacity to be the originator of goal-oriented actions.

The second point that the physicalist seeks to drive home is that it is possible for any kind of object- simple or complex; inanimate or animate, as an accident of nature. It is all a matter of probability. The incredulity of the proposition that clocks and aeroplanes can be accidental is just a personal attitude and not a legitimate argument to disprove the proposition, say the physicalists. The evolutionists and atheists propagate this idea passionately that it has come to acquire the status of ‘an established truth’.

According to the evolutionists like Dawkins, complexity is the property of an object that has a very slim probability of existing in nature but which still does. Mountains are not complex because their components are in a wide variety of configurations and the aggregate would still be a mountain. Only an object conforming to an archetypal plan (like a clock, aeroplane, humans) would get its respective name and become a complex object.

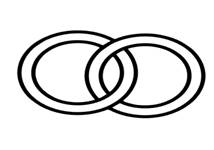

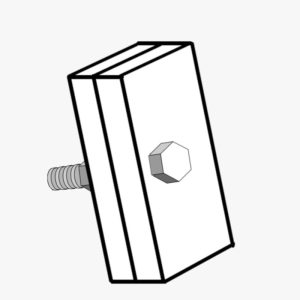

The author holds that most complex objects would never come by chance. That a clock or a Boeing 747 aircraft, can emerge by throwing pieces of junk around at random is a cavalier attitude not befitting a philosopher. The author takes the examples of the possibility by random mixing or spontaneous transformation of two independent rings into an interlocking pattern and two plates coming together by a nut and bolt as shown below:

The author then shows in detail that there are three primary factors that would prevent such complex object formations by accident of nature. The author examines them in depth in the fourth chapter of the book and in summary, they are:

- Certain Laws of nature: Laws of nature such as Pauli’s exclusion principle prevent certain kinds of spatial configurations of matter from occurring in nature. For this discussion, we can ignore them because such laws are applicable at the particulate level of the universe and not at the level of compounded macro objects.

- The presence of interlocking parts: Complex objects like clocks and aeroplanes will never form by accident because they have interlocking parts that pose obstructions for accidental assembly.

- The phenomenon of decay and decomposition: The phenomenon of decay and decomposition, which is universally applicable to all material things, will prevent the accidental production of the parts of the complex product from ever happening. If the parts themselves cannot come into existence, the possibility of the product by accidents of nature gets occluded.

These factors perpetually close the possibility of the spontaneous emergence of complex objects. And the regularity and repeatability of such occurrences occurring in the presence of living beings would be inexplicable unless one accepts the presence of something over and above the physical configuration of the body.

Objection 4: Complex Objects Can Get Created by Natural Selection

Now, the physicalist takes the help of mutation. Some complex objects of the biological or organic world do come accidentally through natural selection. These appear over extended periods of time through the accumulation of incremental changes by mutation. A specific mutant of the parent gene passes on to its progeny which gives it more ability to survive than those who do not have the mutation. There is no intention or design involved in natural selection; it is a blind and natural process. The accumulation of changes by successive mutations over a great many generations results in the manifestation of a complex organism.

Chittaranjan Naik says that had mutation been a universal phenomenon present both in the inorganic and organic worlds, then the physicalist’s assertion that mutation is a blind process would have been true. But its absence in the inorganic world and presence solely in the organic world indicates that it has a binding relationship with the factor that makes a thing a living thing. Now, we have seen that goal-oriented actions originate in an incorporeal substance in the body (soul) beyond the laws of physics. How can we assume then that the phenomenon of mutation itself is free from influence, either directly or indirectly, by the presence of this incorporeal substance?

There are two sources of intelligence associated with the body of a living being:

- The intelligence that belongs to the soul and which has the capacity of willing the motor organs of the body into goal-oriented activity

- The intelligence that has designed and architected the body and which provides superintendence of the activities that enable it to perform its various activities in a coordinated manner

These two intelligences are analogous to the two intelligences that are involved in the acceleration of a car, the first intelligence being the intelligence of the driver who presses his feet on the pedal of the accelerator and the second intelligence being the intelligence of the designer of the car who has provided the car with the capability to respond to the pressing of the accelerator pedal with an increase in the speed.

The motor organ responds to the will of the first intelligence by springing into activity and performing the actions willed by it. The second consists of the various supplementary functions not directly willed by the first intelligence but enable the motor organ to function. These include the functioning of the bones, the muscles, and so on for the proper functioning of the motor organ. Such a coordinated activity is an engineering feat only achieved by an intelligent entity, and these activities pertain to the second intelligence.

Admittedly, a mutation would result in the production of new genes which pass on from parent to progeny during the process of reproduction. Now, the reproductive act – at least in those species of living beings that propagate through the sexual union – is one of the five motor functions of the body. While the sexual act is itself driven for experiencing pleasure or for begetting progeny, the support functions that enable the entire reproduction process could not have come into existence without the superintendence of an intelligent agent.

Just as there is necessarily some intelligence behind the coordinated functioning of the various parts of a motor car, likewise it needs admission that there is necessarily some intelligence behind the coordinated functioning of the various parts of the human body including mutation itself. Like each function in a motor car has a purpose or a telos, each part and each function in a human body has a purpose. The presence of phenomena such as cell multiplication, copying of genetic information, and mutation is evidence of the presence of a Supreme Being who not only controls the functioning of the bodies of all living beings but also of there being a purpose behind each of these processes and functions of the body.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, scientists such as J.S Haldane, watched with dismay while physicalism began to take over the field of biology. He wrote that the phenomena of life imply a fundamental conception different from those of physical science. Haldane stated that the widely spread popular belief that the physical and chemical structure of a living organism accounts for its specific behaviour was baseless.

Cell replication and gene mutation within the context of cell replication is not phenomena determined by physical processes alone. Evolutionists like Richard Dawkins attempt to use mutation to show how it can lead to cumulative selection and evolution over very long periods of time. But Naik says, they are demonstrating, contrary to what they had set out to demonstrate, that evolution, if true, cannot be a blind process. It would necessarily be dependent on a mutation engineered by an incorporeal intelligence.

While evolutionists try to portray processes such as cell multiplication and mutation as blind processes, they are, at the same time, unable to explain how these processes began to manifest in living organisms in the first place. As seen before, a very complex object like a living organism capable of performing cell division and cell replication cannot be done by accident. There is occlusion of its creation firstly, by interlocking parts which prevent their assembly by accident and, secondly, by the universal phenomenon of decay and decomposition which prevents the formation of parts of the complex object from the chaotic conditions of matter. The creation of the bodies of living organisms is not the result of a set of physical processes but is the handiwork of an Intelligent Being, says Chittaranjan Naik.

QED

Random dispersions of matter do not rearrange themselves into ordered dispersions of matter when left to themselves and to the laws of physics. The probability of it occurring would be so minuscule that it would likely take a million years or a billion years for the result to actualize in the world. Yet, when human beings with the intent to produce such ordered dispersions of matter are present, these events do occur many times over; even millions of such ordered dispersions every month or every year. There is a correlation along with temporality of the highest order (when A comes before B, the correlation is near 1; when B comes before A, the correlation is near zero). Such correlations prove A causing B; in this case the soul causing ordered physical matter from disorder.

Evidently, the presence of human beings introduces something more into the situation than the behaviour of material objects operating solely under the physical laws. One needs to presuppose the presence of some entity, namely the self or soul, as a resident within the body of the human being. Ordinarily, this would suffice to prove the existence of the self because it constitutes a valid inference.

Yet, the contemporary world views intentional or goal-oriented action as a manifestation of some underlying physical process in the body or brain. Therefore, a thorough examination of all the objections raised by the physicalist shows them as mere dogmas. As a corollary, the invariable correlation between goal-oriented actions and the presence of living beings (the origin of the goal-oriented actions) points to the existence of an element, namely the soul, within living beings. Thus, purely physical causes and physical processes cannot explain goal-oriented actions. It follows then that the physical world does not form a causal closure.

In the next part, the author distils the Indian traditional view of the Self or the soul. He also lays the logical basis for refuting the Western criticisms of the conception of the soul.

PART 3

In part 1 and part 2, we saw the author’s proof of the self’s existence through its power of jnana shakti and kriya shakti. He also sets the verifiability criteria for his proof. In this section, the author describes the Indian traditional view of the Self and the issues related to the non-Self. He also lays the foundational basis of the logic which sets to refute the western criticisms of the notion of the soul in the final part.

THE NATURE OF THE SELF- ETERNAL AND INDESTRUCTIBLE

The author now elucidates in detail the nature of the Self in Indian philosophical traditions. The self is not an object; it is the subject that cognizes objects. That which is cognized is the object. Material things are objects cognized through the senses. Thus, because it is not a material thing, the senses can never perceive the self. The self is also not an object of thought. Anything thought in the mind would stand known to the self, the cognizer, as a cognized thing and would thus not be the self. Thus, none of the qualities or attributes perceived belong to it. Thus, describing the self can only be in negative terms as being entirely devoid of any kind of form, parts, and attributes.

Without form, it cannot change from one form to another form; without parts, there is no change of any internal configuration; and without attributes, there is no difference between what it was, what it is, and what it will be in the future. Destruction entails a change from being existent to non-existent. That which is changeless cannot change from one condition of existence to another. The self is therefore unchanging and indestructible.

Consciousness Is the Self, The Subject, The Referent of The Word ‘I’

Consciousness accompanies every experience. In every experience, the expression “I know” denotes the state of being conscious. In the sentence “I know a cow”, “I know” denotes the state of being conscious and the latter part of the expression- “a cow”, denotes the object that the subject ‘I’ is conscious of. Even those experiences in the form ‘I am happy”, “I feel pain”, and so on, are cognitive states as a knowledge of being happy or in pain that accompanies the mental state of being happy or in pain. This is because consciousness is self-revealing and a consciousness accompanies not only the things experienced but also of the experience itself. In a certain sense, it may be that even a robot or AI is ‘seeing’ or ‘hearing’ something like a human being but it is only the latter that has a self-awareness that says ‘I know that I see or hear.’ Consciousness’s own special power of self-luminosity or self-consciousness reveals to us its presence in every experience we undergo.

Change pertains to objects of consciousness only. The changeless consciousness cognizes the change. Expressions such as “presence of consciousness” and “absence of consciousness” refers to the presence or absence of objects on which consciousness shines and not consciousness itself. Deep sleep and death are therefore not conditions in which there is the absence of consciousness; they are states with no objects to reflect consciousness. The unchanging, eternal, and indestructible self has neither birth nor death.

The Self and The Non-Self

In the tradition of Western philosophy, the distinction between the self and the non-self is unclear and hazy. The soul (or the self) often conflates with the mind. Resultantly, consciousness and mind mean the same leading to confusion to define the ‘relationship between mind and matter’. The confusion between the terms ‘soul’ and ‘mind’ prevails unto this day. Western tradition’s attempts to grasp the true nature of the relationships between soul and mind, on the one hand, and between mind and matter, on the other has been only that of confusion. The treatment of these two different relations conflates into one single confusing ‘mind-matter’ relationship.

Indian traditions are clear on the conception of the self or the soul. The self is neither mind nor matter; it is pure spirit, formless, imperceptible, and inconceivable. Everything else, including the mind, is the non-self. While the self is a single entity bereft of parts or attributes, the non-self consists of three layers or domains of existence.

The Three Layers of The Non-Self

The first and most familiar layer is the domain of gross physical objects; objects known by means of perception. In Western philosophy, it has become problematic to maintain that perceived objects are physical objects on account of the stimulus-response theory of perception. The objects thus perceived would be subjective phenomenal objects and not external physical objects. Indian philosophical tradition espouses Direct Perception where the self directly perceives the external objects. The perceived world is a legitimate world of physical objects.

The second layer is the domain of ideas or ideated objects. The mind invokes the objects to appear by the mere exercise of an individual’s will. The relation between mind and matter refers to the relation between an object of ideation as it appears in the mind and the object, referred to by the same name, as it appears in the world of gross physical objects. The appearance of objects in these two layers does not pertain to two different objects but to two different conditions of existence of the same object. Thus, Indian thought resolves one of the most perplexing problems in the Western tradition- the relationship between mind and matter. In Indian philosophy, they are simply two existential conditions of an object denoted by a name.

The third layer is the domain of the unmanifest. This layer is the repository of all objects, albeit in their universal natures. Any physical or ideated object exists perennially in the layer of the unmanifest. It emerges into the world as a created object or in the mind as an imagined idea. There is no such thing as absolute non-existence of a legitimate object. Upon the destruction of any object, it simply becomes unmanifest and comes to abide in a state of formless rest. This layer is the region of universals wherein each object abides in its universal ‘form’; paradoxically, that universal form is formless. This layer is the nothing that is cognized in the state of deep sleep. Due to its formless nature, one mistakes the third layer as the self.

This objective reality, which consists of three layers of objects (triloka or three worlds), is the Prakriti. Purusha or the Self is the witness of the three worlds. Western philosophy does not make a clear distinction between the self and the three layers of objective reality. Thus, there is often a derailed reasoning for ascertaining the existence of the soul due to a lack of discrimination between consciousness and one of the three layers of objective reality.

On the Individual Self- Ego

The self is attributeless. That which is without attributes cannot exist as an individual thing. Therefore, in truth, there cannot be such a thing as an individual self. The individuality of the self does not derive from the intrinsic nature of the self; it is the result of an erroneous identification with the body. The notion of the individual self is parasitic upon the limited sphere of consciousness reflected off the intellect and the inner layers of the mind.

The limitedness of the sphere of reflected consciousness brings about the notion that the self is within the space of the body. The identification of the self with the intellect explains the notion of the limited self. However, this does not account for the unique individuality of the individual self. The uniqueness derives from the history of the soul’s actions and experiences in the passage of time.

The knowledge episodes of these experiences etch within the inner layers of the mind as a memory-repository. It is the uniqueness of this repository that provides the individual self with a unique identity. According to the philosophy of Vedanta, at a deeper level, the unique individuality of a soul derives from its adrshta, the balance of the effects of its past actions or karma. If there is no adrshta, there is no individual self.

The self is not the ego. The ego is the I-sense that appears in the mind and it belongs to the realm of the non-self. In the Indian tradition, it is known as the ahamkara, the form (akara) of the ‘I’ (aham). The ego is the medium through which the body gets appropriated as the self. It is the ego that sustains the facade of the self-being an actor in the world.

Will and The Arrows of Causality

The foremost question is about the existence of will. The question is whether there exists within living beings a power to exert extra-natural force to influence the behavior of physical objects. As the author shows previously, living beings do possess the power of exercising intentional force which not only invoke the motor organs into activity but organizes the motor organs for coordinated activity. This establishes the existence of the will.

In a purely physicalist framework, the arrow of causality would be from a physical body (or phenomenon) to another as both the cause and the effect would be attributes of physical bodies. The rejection of Cartesian dualism in contemporary culture has resulted in consciousness relegated to a position of an insubstantial non-entity. Thus, in the physicalist framework, the arrow of causality never originates in consciousness nor does it point to it. As an epiphenomenon, consciousness is an accompaniment of certain brain processes. Contemporary scientists and philosophers take the position of the physical causal closure argument – all phenomena in the universe have solely physical causes.

The existence of will in living beings dismantles the physical causal closure argument and establishes that the arrow of causality also points from consciousness to physical objects. Consciousness can exercise will and thereby cause changes to occur in physical objects unexplainable by physical causes alone. The notion of the physical world forming a causal closure is mere dogma.

The pernicious dogma needs to abandon to accept an incorporeal cause as a power that operates alongside the physical causes of the universe. The arrows of causality are not only from physical objects to other physical objects but also from the self to physical objects. It is important to understand that the presence of will as an extra-natural power does not impinge upon the validity of the physical laws. They both exist alongside each other.

On Free-Will and Determinism

Unfortunately, the debate on free-will verses determinism has characterized the presence of will and the presence of physical causality in terms of an either-or proposition. The problem thus lies not with the nature of the causes but by the postulation that the causes acting in nature can either be physical causes or a will exercising its freedom of action. The author calls it a mistake. They both exist together, interpenetrated with one another in reality. The exercise of will does not affect the validity of the physical laws any more than the presence of a magnetic force that causes a piece of iron to lift in the air affects the validity of the gravitational force that would be acting downward on the piece of iron.

The various forces act in accordance with the laws that are applicable to them, whether physical or incorporeal, but it is only the net effect of the forces that become obvious. The question of free will is towards knowing the extent to which it would be free in exercising its powers. Obviously, the will of a living being does not have unlimited power. The power of will limits to moving motor organs into activity, and the motor activities act on the external object in a manner that would serve the purpose of exercising the will.

The strength and vigor of the instrument (like the muscles or brain) limit the power of the will. In general, the freedom of will is like the freedom that an animal tethered to a pole by a rope has. Beyond the radius provided by the rope’s length, it finds its movement obstructed. A living being enjoys a certain radius of freedom beyond which there is a limiting of powers. The world and the external circumstances place constraints. There are also internal constraints in the form of mental predispositions whose forces and momentums have the potential “to carry off a person’s mind” and make it act along with the veneer of its desires rather than by the dictates of reason.

The force or impulse of desire caused by such internal mental tendencies can render the will a slave of its instincts and desires. Such a will is not free. It is the state of will that exists in animals and other lower beings which retain the power of exercising their wills but do so as driven by their instincts, desires, and mental tendencies rather than by the exercise of intellect. The forces exerted by mental dispositions and tendencies belong to the non-self, that is, to prakriti and not to the purusha or the self.

Thus, a will held hostage to the tendencies of the mind (forces from prakriti) cannot be free. Free will must consist of exercising its powers and abide by its own independent nature. External forces, residing both inside the body and outside, should not be able to influence its exercise. What is its own independent nature? The self is of the nature of pure consciousness or pure knowledge. Therefore, in acting freely, the directedness of the actions that proceed from the will would be determined solely by the nature of the self, that is, by knowledge and the power of discrimination (viveka) that comes from knowledge, and not by the impulses of desire or the forces of mental tendencies.

Thus, the actions that proceed out of free will would be actions determined solely by the knowledge of the factors involved and a determination of what constitutes right action in the situation. Mental tendencies and desires should not propel the actions. One who acts in this manner through the exercise of his free will instead of by the impulses of desire or mental tendencies is acting in a noble manner (an arya way) in Indian traditions.

THE LOST ARK OF THE LOGOI: INDIAN LOGIC AND CONTEMPORARY LOGIC IN THE UNDERSTANDING OF REALITY

Aristotle enumerated the categories- the most general kinds, into which entities in the world divide. The following are the highest ten categories of things that exist ‘without any combination.’ (source: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/categories/)

- Substance (e.g., man, horse)

- Quantity (e.g., four-foot, five-foot)

- Quality (e.g., white, grammatical)

- Relation (e.g., double, half)

- Place (e.g., in the marketplace)

- Date (e.g., yesterday, last year)

- Posture (e.g., is lying, is sitting)

- State (e.g., has shoes on, has armour on)

- Action (e.g., cutting, burning)

- Passion (e.g., being cut, being burned)

There are two sorts of substance: a primary substance is, for example, an individual man or horse; the secondary substances are the species (and genera) of these individuals (e.g., man, animal). While all the ten categories are all equally highest kinds, primary substances have a priority since without them the others do not exist.

Aristotle apparently arrived at his list by distinguishing “different questions which may be asked about something” and noting “that only a limited range of answers can be appropriately given to any particular question”. A categorial realist approach provides the most general sort of answer to questions of the form “What is this?”, and providing for narrower definitions and distinguishing from other things in the same category. Scholastic philosophy too used the categories in its arguments of logic. Categories defined the legitimate ways in which we may speak about objects.

In the Post-Cartesian period, however, when the very existence of external objects became doubtful by an Indirect Realism, categories as descriptions of the world objects lost their legitimacy. Contemporary philosophers have done away with the categories, the basic constitutive elements of objects. With the development of modern science and philosophy, scientists and philosophers sacked and destroyed the categories of the logoi, which had once been the stable ground for philosophy. Science had no use for the categories. Philosophy, following the scientific paradigms, rejected the categories. Berkeley, Hume, and Nietzsche completely buried the categories in their writings.

Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason, did restore some of the respect accorded to the categories but scientists were not much concerned with his ideas because what mattered to scientists was that the theories they constructed worked rather than that the philosophical justifications that made the principles they used possible. The author asks, what was the ground on which the categories became mere products of the fertile imagination? Was the inability to perceive an entity by itself an enough ground for its denial? This is a crucial point, but one which may not be obvious to a philosopher from the Western tradition because Western philosophy has never treated non-existence as an independent category.

But Indian logic has; and it has also provided the epistemic means to ascertain the non-existence of an object. In Indian logic, the mere absence of perception of an object is, by itself, an insufficient ground for denying the existence of the object. It needs another condition called the pratiyogin – its amenability to perception under the given condition. To declare that an object is non-existent on the ground of it being unperceived, it must have a prior possibility of perception if it were to exist.

A chair in front of me has the possibility of perception if it were to exist. The non-perception of a chair in front of me is a justifiable reason for me to claim that it is non-existent. But I cannot justifiably claim that a chair in the next room is non-existent on the ground that I do not perceive it because even if the chair were to be existent in the next room, the wall of the room would prevent me from perceiving it. Thus, to repeat, the claim of the non-existence of an object should therefore be based on the prior possibility of perception if it were to be existent. The capacity of perception if it were to exist is ‘pratiyogin’. And the means of obtaining knowledge of non-existence based on non-perception is ‘anupalabdi’. In western traditions, the non-perception of the soul simply translates into non-existence. In examining the refutations of the existence of the soul proffered by Post-Cartesian philosophers, the author abides by the principles of Indian logic.

As shown in ‘Natural Realism and Contact Theory of Perception’, in a veridical perception, the perception of the world and its objects are direct and transparent. Indian logic, which accepts perception as the first of the means of right knowledge (pramana), does not have the problems faced by the western traditions. In the latter, its locutions of the world divide into locutions of subjective phenomenal features of objects and locutions of external objects that cannot be known (noumenon) by first-hand experience. In Indian logic, there is no such division and one may legitimately speak about the perceived world as the real world.

There is thus no legitimate reason in Indian logic to dispense with the categories; rather, they form the bedrock of logic. The categories or padarthas as they are known in the Indian tradition are the irreducible word-objects that logically constitute the individual objects of the world, and they are held to be seven in number, namely dravya (substance), guna (attribute), samanya (universal), vishesha (particular), karma (action), samavaya (inherence) and abhava (non-existence). The predominant form of contemporary logic is formal logic in which it is the syntactical form (the proper construction) of the argument that determines validity rather than the semantic content (the meaning) of the argument (as in Indian logic).

In contemporary formal Logic, the goal is not truth; it is the preservation of truth-values from the parts to the whole. The goal of Indian Logic, on the other hand, is towards the right cognition of objects (yathartha-jnana) that linguistic expressions purport to speak about. Contemporary logic, standing on the topic-neutrality of logic, keeps itself free from ontology (the reality). Nyaya, or Indian Logic, rejects this hypothesis and holds that reasoning is impossible in the absence of knowledge of the padarthas or word-objects.

The padarthas are the generality (equivalent to the categories of Aristotle) present in the objects themselves in the form of the basic irreducible elements that linguistic expressions point to. The explicit knowledge of the padarthas- padartha-tattva-jnana (the knowledge of the categories as principles) is mandatory to prevent fallacious reasoning. Nyaya, or Indian logic, based on the padarthas- the most fundamental set of word-objects, thus obtains a sweeping universality lending to it the power to conduct discourses on every topic of human interest that language can express.

In the final part, the author refutes the influential western philosophers’ rejection of the notion of the soul. He also rejects the arguments against Descartes’ idea of the soul by some western philosophers.

PART 4

In the previous three parts, the author shows the existence of the soul through its powers of jnana shakti and kriya shakti. He also gives a clear idea regarding the Indian thought on the Self and reality. Further, he lays the foundational basis of Indian logic based on Nyaya with which he refutes western philosophers arguing against the concept of soul and substance in this last part. He also provides a defence to Descartes’ notions who has undergone an unwarranted rejection in contemporary philosophy.

An examination of Hume’s refutation of the existence of the soul

In his books and essays, Hume provides various arguments to reject that the soul is a substance and that it is immortal. Chittaranjan Naik examines each of the arguments in detail and shows that most of Hume’s arguments suffer from fallacious reasoning and a failure to consider alternative descriptions of ‘reality’ not only of the Indian philosophical traditions but also of the Scholastics. Hume considers the notion of substance to be a dogma born out of the fertile imaginations of Aristotelian and Scholastic philosophers. Naik shows that Hume also asserts from dogma.

Hume’s fallacious arguments originate from his inability to apprehend the natures of substance and the relationship that abides between substance and attributes; it also stems from his inability to grasp the natures of ‘universals’ and ‘particulars’. Hume confuses between the soul and the mind in a manner that is characteristic of Western philosophers. He conflates the different changing states of the body and the mind to the unchanging self- a distinctly different substance. In effect, it amounts to nothing more than a dogmatic assertion of Hume’s own position restated as an argument. Briefly, the arguments of Hume and the responses of Naik are as follows:

- The soul is not a substance because:

- The idea of substance makes no sense.

- The definition of substance does not hold.

- The attributes it possesses cannot be related with one another in a meaningful way.

- We have no idea of anything except a perception.

- The idea of soul is not from an impression.

- No meaningful conception can form of its union with material objects.

The author examines each of these positions in the book and in each case, Hume’s arguments are shown to be untenable. Hume’s entire philosophy is based on the idea that there are only two kinds of things present in the universe: impressions (qualities) and ideas (derived from impressions). There is only one reason offered by Hume, namely that nothing else is in perception other than the impressions, i.e., the qualities such as colour, touch, sound, taste, and smell. And we have the power to contemplate upon these impressions in the form of ideas. These constitute the furniture of the world. All else is the power of imagination.

These notions intimately link to the belief in the stimulus-response theory of perception. If Hume had considered the alternative thesis, namely that perception is an active process in which the percipient reaches out to the object, and arrived at his conclusions after considering the merits and demerits of both positions, his thesis would have qualified to be a legitimate philosophical position. But the failure to question the premise, and to proceed to draw conclusions without taking into consideration the possible alternatives to the premise, reduces his entire thesis into a dogma.

There is a difference in the way Western and Indian traditions conceive of ‘substance’. The former holds substance the ‘thing’ leftover after abstracting its attributes. But conceiving substance in this manner leaves over a ‘bare individual’ bereft of any distinguishing feature. This gives it no identity to differentiate from others. Such a difficulty does not arise in the Indian tradition because substance (dravya) in the Indian tradition goes along with its attributes; and the essential attribute of substance is existence. Naik shows how Hume rejecting the notion of substance leads to all kinds of absurdities. Hume’s scepticism becomes merely a destructive tool and it leaves the original questions in a barren soil with no philosophical answers.

In the Indian logical tradition, non-existence is a padartha, an object. For an object to be non-existent on the ground of it being unperceived, it must have a prior possibility of it being perceived if it were to exist. If a chair is in front of me, I can perceive it. Hence, if I can perceive a chair it is existent; if I do not perceive the chair, it is non-existent. But I cannot justifiably claim that a chair in the next room is non-existent on the ground that I do not perceive it. Even if the chair were to be existent in the next room, the separating wall obstructs its perception. The very nature of the soul is that of the cognizing subject and not that of an object of cognition. How can one declare its non-existence on the ground that one cannot perceive it or that we possess no impression of it? Hume’s argument to show that the soul is non-existent is ineffective.

The self has a unique characteristic- self-luminosity. It reveals itself. The existence of self-luminosity would be evident if we consider that in every cognitive act, we know not only the object but we also know that we know the object. Thus, there is a kind of knowledge, namely self-knowledge, which reveals itself in every episode of knowledge. Hume fails to consider this aspect of human knowledge because it does not appear as a theme in the philosophical tradition of the West.

- The soul does not exist because one cannot fix a personal identity for it.

Hume’s arguments stem from the Western tradition’s unclear conception of the soul, mind, the world, and the process of perception unlike in the Indian philosophical traditions. Hume also does not believe that things such as universals exist just as he does not believe that substances exist. He takes each temporal instantiation of a changing object to be different object and proceeds to declare that there is nothing in the flux of change that conforms to the notion of identity.

Naik says that this kind of loose reasoning would result in the object presented in each instance of perception requiring a new name and such indiscriminate naming of objects would not only make language dysfunctional but would also result in ‘reality’ becoming amorphous and unrecognizable. Hume also denies sameness between an impression and an idea that corresponds to the impression thus making it impossible to sustain the position that an idea corresponds to a particular impression. Indian traditional philosophy denies this position. In the latter, it is the universal that accounts for the sameness and the difference in the modes of presentation that accounts for the difference. The ‘particular’ or individual is nothing but a crystallization of the universal into concrete form.

- Memory does not acquaint us with the continuity of a soul.

Hume asserts the absence of perception in deep sleep and after death as evidence for the absence of the soul. From another perspective, Indian traditions hold that it is not the absence of perception but the absence of objects of perception in the field of awareness that leads to the condition erroneously described as the absence of perception. The awareness of the sense of time in deep sleep is evidence for the persistence of self-luminosity even in deep sleep. To sum up, the absence of objects in the field of consciousness cannot be evidence for the absence of the self. Considering that Hume does not consider other possibilities for the non-perception of objects during deep sleep or death, his rejection of the existence of the self does not hold since it is based on insufficiency of reason.

Hume argues regarding a person who performed certain actions that the subsequent absence of memory would make the person a different person. This argument is fallacious. What ought to interest a worthy philosopher investigating the topic of the soul is not so much the absence of memory of certain events but an explanation for the recall of past experiences in memory. Unless there be a substrate, unique to every person, and which acts as a repository of the knowledge of the past experiences, such recall would not be possible. Personal identity is not from memory; it is from the fact that there is such a thing as memory at all and that such memory has consciousness as its necessary substrate.

- The soul is mortal because all things in nature are subject to change and decay. Also, the condition required for its existence does not exist after the dissolution of the body.

Hume says: ‘As the same material substance may successively compose the bodies of all animals, the same spiritual substance may compose their minds. Their consciousness, or that system of thought which they formed during life, may be continually dissolved by death.’ Hume illegitimately reasons to extend the properties of one category (material things) to a completely different category (the soul). Hume finally says that even if we should grant that the soul is immortal, immortality would not have any significance to us. This is obfuscation again since the subject matter of the discussion is the immortality of the soul and not about the implications of its existence.

An examination of Kant’s refutations of the soul as substance and its immortality

Emmanuel Kant describes the transcendental approach as a Copernican revolution in philosophy where he refutes both the existence of the soul as a substance and its immortality as Socrates had suggested. He says that the possibility of experience is by the paraphernalia that lies ready a priori within us. The discovery of such a priori principles which make experience possible was the goal of a new ‘Transcendental Philosophy’. One would expect that a philosopher who advocates such an approach would affirm the existence of the soul as the repository of paraphernalia. While Kant does not reject the existence of the soul as such, he says that reason is incapable of affirming its existence or its nature as a substance. The existence of a permanent or immortal soul is also indemonstrable.

According to Kant, the use of reason to demonstrate the existence of the self would result in a sophism, or a kind of illusion. Kant says that such reasonings constitute a transcendental paralogism in which the form of the argument may be correct but the conclusion is false and illusory.

The reasoning for the existence of the soul, says Kant, rests on the single conception ‘I think’. But such a science, says Kant, is only a pretended science as it rests solely on the statement ‘I think’ from which it must develop its entire science. It cannot rely upon even the smallest object of experience, for the presence of such empirical content would change the science from a rational science into an empirical science and would render it incompatible with its object, the soul.

Chittaranjan Naik examines the paralogisms in detail that Kant presents to show that the existence of the soul is a pretended science and that its arguments are sophisms.