Hindu scriptures divide broadly into the srutis (that which is heard) and smrtis (that which is remembered). Vedas constitutes an important part of Indic culture and civilization, but by no means the only one. Also, a belief or disbelief in the Vedas does not in any way reflect upon the status of a being a Hindu or belonging to the Indian civilizational heritage.

Five groups of texts – Veda, Upaveda, Vedanga, Purana, and Darsana – lay the foundation for the knowledge and the wisdom of our heritage and cover the concrete and the abstract, the secular and the spiritual.

Vedas

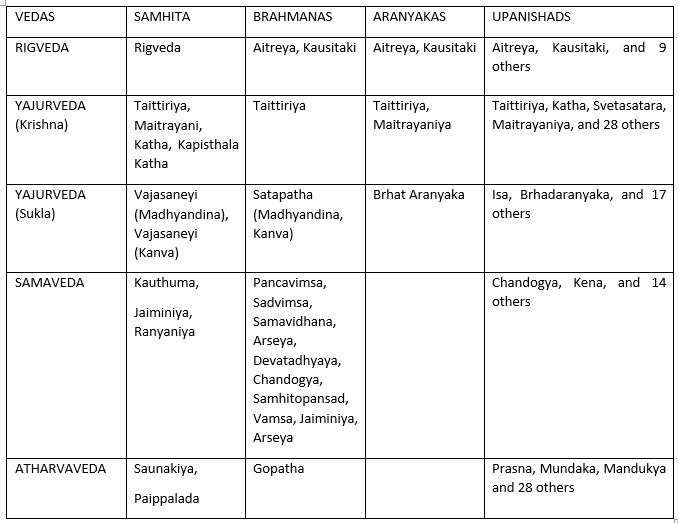

There are four Vedas which are the core sruti texts: Rigveda (rks or verses), Yajurveda (yajus or prose), Samaveda (samans or songs), and Atharvaveda (Sage Atharvan’s compositions).

Each Veda further sub-divides into four sections: Samhita, Brahmana, Aranyaka, and Upanishad. The Samhitas deal with bhakti (devotion), the Brahmanas with karma (work, action, ritual), and the Aranyakas with dhyana (meditation). These three dealing with rituals and devotional activities form the Karma kanda.

The Upanishads (or Vedanta, the final portion of Vedas) form the Jnana kanda– treatises on the philosophical aspects and deep discussions on the body, mind, soul, nature, consciousness, and the universe. Of the several Upanishads (at least 108 of them), ten are most important: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, and Brhadaranyaka.

Loosely, the Vedic divisions also associate with the ashramas or stages of life: the Samhitas to brahmacarya (student); the Brahmanas correspond to grhasta (householder); the Aranyakas correspond to vanaprastha (forest dweller), and the Upanishads correspond to sanyasa (the ascetic).

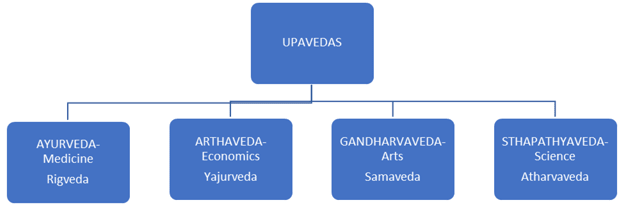

Upavedas

Upavedas (upa or ‘secondary’ to Vedas) are bodies of secular knowledge though still intimately linked to spiritual insights. Each Upaveda corresponds to one Veda.

The Upavedas and Vedas also support the classical concept of Purusartha, the four objectives of life: dharma (duty), artha (material wealth), kama (intellectual desires), and moksa (liberation, freedom).The Upavedas concern mainly with artha and kama (‘pravrtti’ or practice in the outer world); while the Vedas are about dharma and moksa (‘nivrtti’ or practices for the inner world of Self-realization). However, these are not at all strict as there is an expected overlap in the purposes in the huge corpus of literature.

Ayurveda is the medical and surgical science and some foundational texts include Susruta Samhita, Caraka Samhita, Astanga Hrdaya, Vagbhata Sangraha, and Bhavaprakasa.

Arthaveda is the wisdom of not only economics but also political science, law, ethics, constitutional studies, defence, management, sociology, trade and commerce, civil and military engineering. Some of the renowned Arthaveda tests are: Arthasastra (Kautilya), Pancatantra, Yuktikalpataru, Nitikalpataru, Nitisara, Hitopadesa, Nitisutra, Nitivakyamrta, Vyavaharamayukha, Rajanitimayukha, and Rajanitiratnakara.

Sthapatyaveda forms the wisdom of engineering. Sthapati was a head engineer under whom were sutradharas (design engineers), silpis (sculptors), karukas (artisans), taksas (carpenters), karmaras (blacksmiths), kaladas (goldsmiths, silversmiths), kulalas (potters), tantuvayas (weavers), and so on. Sthapatyaveda includes basic sciences physics, mathematics, and chemistry and their applied forms like mechanical engineering, civil engineering, chemical engineering, hydraulics, mechanics, and dynamics. Texts of Sthapatyaveda included Manasara, Mayamatam, Visvarupam, Aparajitaprccha, Samaranganasutradhara, and Rupavastumandana.

Gandharvaveda is the wisdom of arts and crafts. The Yajurveda mentions twenty-eight types of arts and crafts. The number of arts and crafts increased over time and later literature mentions the famous sixty-four arts (chatursasti kala). This includes not just the fundamental arts like poetry, music, dance, theatre, painting, and sculpture but also secondary arts like flower arrangement, magic, juggling, carpentry, and so on. Some of the important texts are: Kamasutra, Naṭyasastra, Kavyalankara, Kavyadarsa, Dhvanyaloka, Srngaraprakasa, Sarasvatikanthabharana, Vakrokti Jivita, Vyakti Viveka, and Kavyaprakasa.

The famous Kamasutra (Sage Vatsyayana- period between 400 BCE to 200 CE) discusses love and love-making with an overall awareness towards a person’s life and society and includes discussion on sociology, aesthetics, ethics, medicine, anthropology, and psychology.

Natyasastra (Sage Bharata- period between 200 BCE and 200 CE) is a comprehensive encyclopedia of all performing arts as well as literature and architecture. It deals with the emotions, sentiments, and moods of theatrical communication. It deals with methods of presentation; creativity; vocal and instrumental music; lyrics; grammar and figures of speech; stage construction, building sets and architecture; costumes, jewellery, and make-up; and the education of the actors, dancers, and connoisseurs.

Some scholars include Dhanurveda, the science of archery, as one of the Upavedas. However, there are no foundational texts specifically under Dhanurveda.

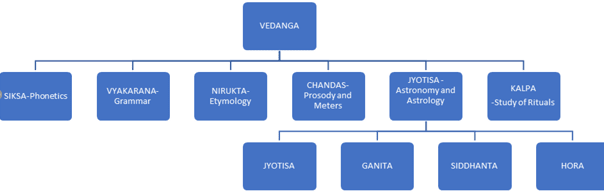

Vedangas

Vedangas are the limbs (angas) of knowledge (veda). They are the six auxiliary disciplines essential to the study of the Vedas – phonetics, grammar, prosody, etymology, astrology/astronomy, and ritual.

Siksa (phonetics, phonology) is the study of pronunciation of language. Siksa reveals the sophistication of the Sanskrit language and of the Vedas. The texts on Siksa include: Rigveda Pratisakya (Sakala Sakha), Sukla Yajurveda-Pratisakhya, Taittiriya Pratisakya, Atharvaveda-Pratisakya (Saunakiya Sakha), Saunakiya Caturadhyayika, Yajnavalkyasiksa, Naradasiksa, Mandukisiksa, Paniniyasiksa, and Siksasangraha.

Vyakarana is the most important study of grammar. Sanskrit grammar, especially the system of Panini, is known for its perfection, richness, depth, and beauty. Texts on grammar include: Astadhyayi (Panini), Vartika (Vararuci), Mahabhasya (Patanjali), Vakyapadiya (Bhartrhari), Madhaviyadhatuvrtti (Sayana), and Siddhantakaumidi (Bhattojidiksita).

Nirukta, the study of etymology, is auxiliary to the study of grammar. Grammar tries to develop a word while etymology tries to analyze it. The texts are: Nighantu (Yaska), Nirukta (Yaska), Amarakosa (Amarasimha), Trikandasesa, and Vaijayanti kosa (Yadavaprakasa).

Chandas, the study of prosody and rich poetical meters of Sanskrit, is extremely crucial to understand the verbal utterances of hymns from the Veda. The texts include: Chandas Sastra (Pingala), Vrtta Ratnakara (Kedarabhatta), Chandonusasana (Hemacandra), and Chandanusasana (Jayakriti).

Jyotisa includes astronomy and astrology. The former is the factual description of celestial bodies and their behaviours. Astronomical observations, mathematics, and calendar making were the highly interlinked deepest skills of ancient Indians. Astrology, a probabilistic system, based on the above three got prominence in the narratives of a superstitious India unfortunately.

Four sub-sections that come Jyotisa group are: Jyotisa (astronomical observations), Ganita (mathematics), Siddhanta, and Hora (astrology). The texts are: Vedanga Jyotisa (Raladha), BrhadSamhita (Varahamihira), Brhadjataka (Varahamihira), Aryabhatiyam (Aryabhatta), Suryasiddhanta (Bhaskara), and Siddhanta Siromani (Bhaskara).

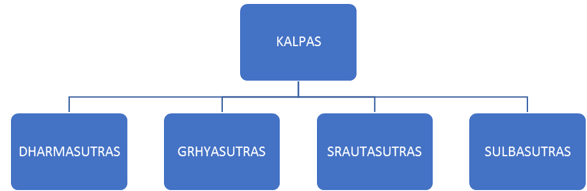

Kalpa, the study of rituals, covers a vast expanse of knowledge including ethics, sociology, polity, traditions, and worship. It has again four main sub-groups of texts: Dharmasutras (rituals, duties, and responsibilities at a societal level); Grhyasutras (household rituals and duties); Srautasutras (rituals and worship of the Vedas); and Sulbasutras (construction of the altar for Vedic fire ritual).

The Dharmasutras include Vasistha, Apastamba, Baudhayana, Visnu, and Gautama.

The Grhyasutras include: Asvalayana, Kausitaki, Sankhayana associated with Rigveda; Gobhila, Khadira, Jaiminiya, Kauthuma associated with Samaveda; Baudhayana, Hiranyakesi, Manava, Bharadvaja, Apastamba, Vadhula, Kapisthala Katha associated with Krsna Yajurveda; Paraskara, Katyayana, associated with Sukla Yajurveda; and Kausika associated with Atharvaveda.

The Srautasutras include texts like Asvalayana, Sankhayana, Latyayana, Drahyayana, Jaiminiya, Baudhayana, Hiranyakesi, Bharadvaja, Apastamba, Katyayana, and Vaitana.

Finally, the Sulbasutra Kalpa texts include Baudhayana, Manava, Apastamba, and Katyayana.

Consolidation and Further Expansion of Kalpas

A consolidation and further expansion of Dharmasutras and Grhyasutras of Kalpa are a group of eighteen primary texts called Smrtis and eighteen secondary texts called Upasmrtis. The smrtis include the texts of: Manu, Yajnavalkya, Parasara, Visnu, Vyasa, Daksa, Likhita, Atri, and many others.

Agamas are consolidation and further expansion of the Srautasutras and Sulbasutras of Kalpa. They include numerous and voluminous texts dealing with the temple tradition- construction, art and architecture, iconography of the images, as well as the daily, fortnightly, monthly, and annual rituals and festivals observed in the temples. Above all, they discuss the underlying philosophy of the entire system.

The Agamas literature divides into Saiva (pertaining to Siva); Vaisnava (pertaining to Vishnu); Sakta (pertaining to goddess Shakti); Bauddha; and Jaina Agamas.

The Saiva Agamas are Raurava, Mukuta, Karmika and Vatula. The Vaisnava agamas are Pacaratra Agamas, Sattvata Samhita, Ahirbudhnya Samhita, and Laksmi Tantra. The Sakta Agamas are Saradatilaka, Tripurarahasya, and Varivasyarahasya. These Agamas are by no means exhaustive.

Puranas and Itihasa

Amarasimha (fifth or sixth century CE) defined a Purana as having five characteristic topics (pancalaksana): the creation of the universe; its destruction and renovation; the genealogy of gods and patriarchs; the reigns of the Manus, forming the periods called Manvantaras; the history of the Solar and Lunar races of kings.

Puranas consist of stories to educate ordinary people on many topics like famous people, rituals, pilgrimages, festivals, arts, sciences, and so on. They deal with geography, local traditions, history, and folklore with great spiritual insight. There are eighteen Mahapuranas and eighteen Upapuranas.

The Purana literature also includes Sthalapuranas that pertain to local traditions in different places, taking elements from the local folklore and from traditional stories of the Puranas.

The Mahapuranas include Brahma Puranas (Brahma, Brahmanda, Brahma Vaivarta, Markendeya, Bhavisya); Vaishnava Puranas (Visnu, Bhagvata, Naradeya, Garuda, Padma, Varaha, Vamana, Kurma, Matsya); and Saiva Puranas (Siva, Linga, Skanda, Agni).

The Itihasas are the famous epics of India- the Ramayana of Valmiki and the Mahabharata of Vyasa. These literally translate into our ‘history’ but are stories finally with metaphysical, allegorical, and philosophical insights targeting individual liberation. The spirit of Upanishidic message and the four purposes of life especially Dharma runs throughout the two most important Itihasas. The Bhagvad Gita forms one component of the huge corpus of Mahabharata.

Darsana

Darsana, or ‘point of view’ is the English equivalent of philosophy though with different connotations. There are six classical schools of Indian philosophy and three atheistic schools (Jaina, Bauddha, Lokayata/Carvaka).

Nyaya (epistemology) and Vaisesika (ontology) systems largely deal with the physical level; Sankhya(method of reasoning) and Yoga (union of body, mind, and soul) systems largely deal with the spiritual level; Purva Mimamsa deals with the preparation for philosophical pursuits and explains the philosophy of rituals; and the system of Uttara Mimamsa deals with philosophical pursuit and gives means for transcending rituals. Each of the darshanas has a huge number of treatises and authors.

What Represents Hindu religion and to Whom These Texts belong?

These knowledge traditions are not the exclusive hold of any single country, faith, or community. It belongs to anybody identifying as a human being and more so as an Indian. The knowledge base of Indian scriptures and texts is accessible to everyone.

Knowledge always is the supreme divine in Indian traditions and the story of villainous Brahmins withholding this knowledge is simply a colonial narrative which we internalised.

Anti-Brahminism has a relentless story since the 17th century European reports of missionaries and travellers. No evidence seems to change this core narrative even as the auxiliary hypotheses and explanations undergo modifications as pointed out elegantly by Jakob De Roover.

Every research program consists of three elements: a “hard core” of basic theses and assumptions; a “protective belt” of auxiliary hypotheses that surrounds this core; and a “heuristic” or problem-solving machinery consisting of sophisticated techniques.

Scientists regularly encounter observations that conflict with a theory’s predictions and other types of problems. However, there is no discarding of a research program simply because it faces some set of anomalies; instead, its protective belt allows the scientists to cope with these problems by immunizing its hard core against falsification by generating new auxiliary hypotheses.

The basic assumptions about the religion of the Brahmin and its hold over society and education are part of this program’s hard core, whereas other claims concerning Aryan invasion, racial superiority, and the varna ideology are part of its protective belt. The latter ideas form a more flexible set of auxiliary hypotheses, which scholars can modify and revise in the face of anomalies, to protect the research program from refutation.

Indeed, this has happened regularly, not only during the past decades, but also in the centuries before. Between the 17th and the 21st centuries, in the face of empirical and conceptual problems, the auxiliary hypotheses moved, as an example, from an Aryan invasion and conquest to peaceful migration and contact. But the hard core of assumptions concerning stories of a tyrannical priesthood and closing off the knowledge to other people in society remained immune against falsification.

Anyway, in this extraordinary corpus of literature dealing with hundreds and thousands of topics what comes to represent the frozen nature of ‘Hinduism’? A corrupted interpretation of Purusasukta hymn and some selected passages from Manu smrti. Except the Vedas to some extent, none of the smrtis have the status of a wide-ranging powerful truth, normative and prescriptive, across time and space. No political, secular, or religious power enforced these on entire populations.

These traditional texts also inculcate the concept of Yuga Dharma, the changes in societal practices according to time without any change in the basic principles. This allows all the social changes without any violent revolutions. New traditions like Sikhism evolved without disrupting the fabric of society or going against any tyranny of priests and scriptures.

Sadly, the colonial scholars made shoddy translations of a few texts using Sanskrit dictionaries sitting miles away from the traditional learning systems requiring huge amounts of auxiliary grounding even to start learning the Vedas. It takes at least eight years of rigorous training to learn one Veda and westerners became experts in a matter of few years to make their own interpretations. They interpreted what they wanted to see; and our post-independent scholars simply continued this practice by reading the translations.

This was the biggest intellectual violence to our entire civilizational heritage and cultural-literary heritage standing miles ahead of any existing or prior civilizations. But, as scholars have pointed across centuries including Dr SN Balagangadhara, is there a ‘core book’ as the foundational basis for Hinduism? The answer is a resounding no.

Michel Danino quotes David Pingree that India has at least 30 million surviving ancient manuscripts in Indian libraries, repositories, and private collections. They deal with every topic under the Indian sun: philosophies, systems of yoga, grammar, language, logic, debate, poetics, aesthetics, cosmology, mythology, ethics, literature of all genres from poetry to historical tradition, performing and non-performing arts, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, chemistry, metallurgy, botany, zoology, geology, medical systems, governance, administration, water management, town planning, civil engineering, ship making, agriculture, polity, martial arts, games, brain teasers, omens, ghosts, accounting, and much more — there are even manuscripts on how to preserve manuscripts! The production was colossal and in almost every regional language.

Unfortunately, ‘colonial consciousness’ takes hold of many Indian intellectuals, a great consequence of Macaulay’s educational policies. Deracinated and derooted from the ethos of India, these intellectuals, many times holding a dominant power in deciding the narratives, simply believe that a 5000 years old civilization (at the very least) simply had nothing to offer to humanity and were waiting with folded hands for the colonials to come and give us education and other positive values.

All histories are elaborate efforts at myth-making, says Claude Alvares (Introduction to Dharampal’s writings). He says that, therefore, when we submit to histories about us written by others, we submit to their myths about us as well. If we must continue to live by myths, however, it is far better we choose to live by those of our own making rather than by those invented by others. That much at least we owe ourselves as an independent society and nation.

India has a deep intellectual history. It would be far better for sensitizing students to this rather than filling our narratives and textbooks with blanket proclamations of an ‘unscientific, primitive, superstitious India before the colonials came combined with of course stupid fanatics today talking about airplanes and genetic cloning’. Ideas which fix in the minds for a lifetime. Time to change the narratives.

(The author is grateful to Dr Shatavadhani Ganesh on whose series of articles Understanding Hinduism this article is based upon)