1. Indian philosophical systems give a far better explanation of life, the world around us, and God better than the majority of western philosophies.

2. Indian philosophies were pushed away by western universities into the realm of ‘religion’ because they either did not understand it or they wanted to ward off the challenge posed to them as they were potentially providing far clearer answers on the nature of reality.

3. Indian philosophies has an intense power to transform a person leading to moksha , something non-existent in western philosophies.

4. The subservience to science leads to failure in western philosophies. Indian philosophies acknowledge science without the so called clash between ‘religion’ and ‘science’ of the western world. But it does not let scientific achievements come in the way of its ideas.

5. Our successive governments have failed completely to remove this colonial narrative that Indian philosophies are religious, esoteric and thus non secular and non scientific. It is is the greatest tragedy of post independent India.

6. Indian philosophies have no need either of science or even God in its explanation of reality or the world around us.

7. Drawing heavily from various authors, especially Chittaranjan Naik and without claiming any primary scholarship, here is a 5 part series summarising the essentials of Indian philosophies and how different and perhaps even better they are from Western philosophies.

I hope you enjoy them. I would like you to share them too in your circles if possible so that some awareness can be created regarding the richness, depth , and the sheer profundity of Indian philosophies or Darshanas.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN PRAGYATA ONLINE MAGAZINE AS A 5-PART SERIES

Philosophical Systems Of India – A Primer – Part 1

Philosophical Systems Of India – A Primer – Part 2

Philosophical Systems Of India – A Primer – Part 3

Philosophical Systems Of India – A Primer – Part 4

Philosophical Systems Of India – A Primer – Part 5

PART 1

Philosophy in India has been the intellectual canaliser of spiritual knowledge and experience, but the philosophical intellect has not as yet decidedly begun the work of new creation; it has been rather busy with the restatement of its past gains than with any new statement which would visibly and rapidly enlarge the boundaries of its thought and aspiration. The contact of European philosophy has not been fruitful of any creative reaction; first, because the past philosophies of Europe have very little that could be of any utility in this direction, nothing of the first importance in fact which India has not already stated in forms better suited to her own spiritual temper and genius, and though the thought of Nietzsche, of Bergson and of James has recently touched more vitally just a few minds here and there, their drift is much too externally pragmatic and vitalistic to be genuinely assimilable by the Indian spirit. But, principally, a real Indian philosophy can only be evolved out of spiritual experience and as the fruit of the spiritual seeking which all the religious movements of the past century have helped to generalise. It cannot spring, as in Europe, out of the critical intellect solely or as the fruit of scientific thought and knowledge. SRI AUROBINDO

INTRODUCTION

This 5-part series aims to introduce the ideas of the great Indian philosophical systems to the uninitiated. The author claims no expertise or primary scholarship in the subject matter but attempts to disseminate some of the readings he has had in a summary form to some of the curious but ignorant. The books of Ramakrishna Puligandla (Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy), Karl Potter (Presuppositions of Indian Philosophies) and Chittaranjan Naik (Natural Realism and the Contact Theory of Perception) form the core basis of these essays. Hopefully, this should stimulate the readers to explore further and understand how rich and brilliant the Indian systems are and how they significantly compare and contrast with western philosophies in dealing with basic existential questions.

A strictly materialistic or ‘scientific’ view of the process of perception has caused deep troubles for the western philosophical world to date. Indian thinkers and philosophers had a different and perhaps a better understanding of the process of perception which they covered in their treatises almost a thousand years back. It is the most unfortunate debacle of our education systems after independence, a continuation of the colonial legacy, that they ignored teaching the growing generations the richness, depth, antiquity, and sophistication of Indian philosophy.

Philosophy deals with the most engaging questions for humanity: the purpose of life and Universe; reality status of the world; the presence and role of God; the matter-mind relation; and so on. Philosophers equate philosophy with only western thought which, in turn, is either ignorant or dismissive of Indian thought. This is surprising, because any person, irrespective of time and place, can have philosophical insights applicable to the whole of humanity. Thinking about some basic questions concerning humans cannot be the sole prerogative of a narrow group of people (mainly the White Europeans of the West) looking only through certain lenses (either Christian theological or its social sciences which is many times a secularized theology) developed in their cultural milieu.

The West puts philosophy between theology and science. As Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) says (History of Western Philosophy), like theology, it speculates on matters of indefinite knowledge; like science, it appeals to human reason rather than to the authority of a tradition. The separation of theology and philosophy did not happen in Europe until the Reformation (16th century CE). When we accuse Indian philosophy of being ‘religion,’ it is an application of a post-Reformation prejudice (religion – a matter of faith; philosophy – for self-reflection or critique but nothing about God or the soul). Hegel (1770-1831), the German philosopher originated this prejudice and largely fashioned the Western image of India. As Adluri and Bagchee say (The Nay Science), the standard themes were: India only developed an abstract Absolute; it lacks a historical sense; it does not know of concrete individuality; and so on. Once Hegel sent Indian systems to departments of Religion and Indology, Philosophy never reclaimed it.

Indic philosophy has an overriding concern for its ‘soteriological’ power; an insight leading to intense individual transformation from bondage to freedom. There is no sacrifice to reason and experience, but characteristically, Indian philosophy (or Darshanas) does not have an extreme reverence for science. Indian Darshanas, unfortunately, disappeared from popular discourses because its paradigms seemed absurd to the dominant Western discourses. Additionally, western universities (especially German) aggressively pushed Indian philosophical systems as ‘religions’ and hence lacking any validity in a ‘secular’ world.

INDIC PHILOSOPHICAL SYSTEMS: BASIC FRAMEWORK AND THE ROLE OF PRAMANAS

Each of the four Vedas (Rig, Sama, Yajur, and Atharva), the earliest source of Indian thought, consist of four parts – Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, Upanishads; the first three related to rituals and the last to philosophical speculations. They are either successive stages of Vedic literature or suggest parallel ideas. In the Brahmanas portion, ideas of monism start coming when a single supreme principle of both an immanent and transcendent power through all gods, individual souls, and nature takes hold. The Upanishidic teaching (the Vedanta portion or the ‘end of Vedas’) crystallises the notion of absolute monism which calls the Brahman as the all comprehensive only reality, the ultimate cosmic principle, the source and destination of the whole universe, and accounting for individual selves too as Atman.

The core classification of Indian systems as orthodox and non-orthodox is on the acceptance or rejection respectively of the Vedas as a reliable authority. The non-orthodox systems are Charvaka (materialism), Buddhism, and Jainism. The orthodox systems include the six systems called Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisesika, Mimansa, and Vedanta. The orthodox schools come in pairs; broadly, the first pertains to practice, the second element to theory: Yoga-Samkhya; Nyaya-Vaisesika; and Mimansa-Vedanta.

Any knowledge must have certain ‘means’ of acquiring it. Pramana (proof or a valid ‘means of true knowledge’) plays an important role in Indian philosophical traditions. Ancient texts identify six pramanas whose variable acceptance and rejection form a basis for classifying the thought systems. These are:

- Perception or direct sensory experience (pratyaksha)

- Inference (anumana)

- Testimony of reliable authorities (sabda)

- Comparison and analogy (upamana)

- Postulation and derivation from circumstances (arthapatti)

- Non-perceptive negative proof (anupalabdhi).

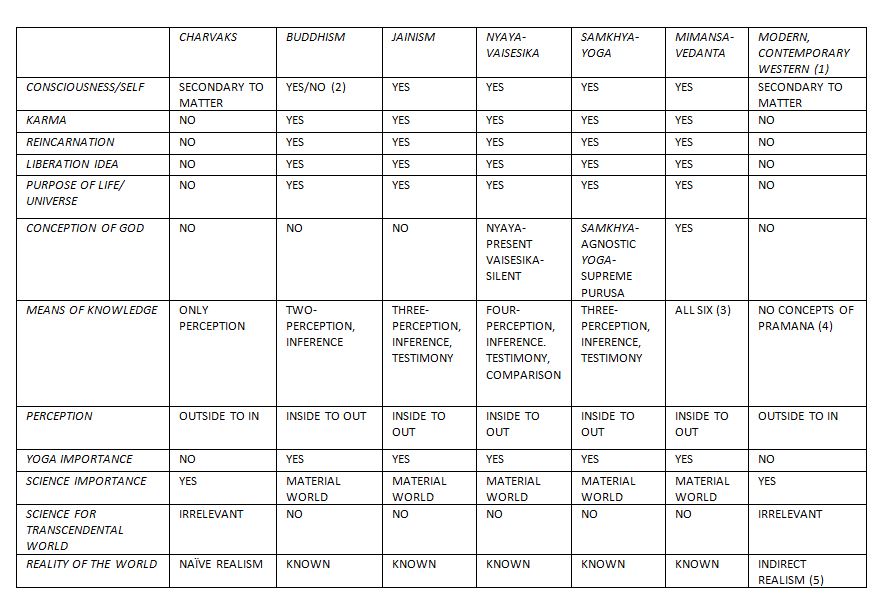

Materialism (Lokayata or Charvaka) holds only perception as a valid pramana; Buddhism: perception and inference; and Jainism: perception, inference, and testimony. Mimamsa and Advaita Vedanta hold all six as useful means to knowledge.

Apart from materialism, both non-orthodox and orthodox schools have certain core ideas of commonality. Most important is that explanation of reality should not sacrifice reasoning and experience. Philosophy, never a dry intellectual exercise, carries a soteriological power – the power of intense individual transformation from ignorance and bondage to freedom and wisdom. There is no original sin but original ignorance. In all systems (except Charvakism), Karma is a central doctrine of cause and effect at the levels of body, mind, and intellect. Whatever one does, it has consequences, if not in this birth, then in a future birth. Karma thus intricately links to the idea of reincarnation in all systems. Moksha, a common theme for all, is the final state of enlightenment with no further births, in stark contrast to western focus for an eternal life. Almost all Indian philosophies accept perfect happiness as a state of no further births.

The practical aspects of Yoga and meditation are acceptable routes in all systems to reach the state of liberation. All stress the inability of senses or intellect to understand reality. Reality is an intuitive, non-perceptual, and non-conceptual experience. All are initially pessimistic in that they speak of ignorance and misery, but ultimately become optimistic as they give immense hope in gaining the state of eternal happiness. All focus on individual effort, if necessary, across many births to liberate from ignorance. The role of a teacher or books is only as a guide on the path, but finally, the individual’s effort is responsible for one’s own moksha, achievable in the present life.

The goal of human life in Indic philosophies firmly remains moksha or enlightenment. The journey starts from an intellectual apprehension of this goal to finally attain moksha through various routes. This is the basic framework of Indian Darshanas. The differences mainly are in the nature of the routes taken to reach there. The multiple routes are all valid like ‘various rivers merging into one ocean.’ The distinguishing feature of the varied paths is ‘an indifference to differences’ with each taking its view as the valid one (‘I am true, but you are not false’). The concept of truth stays robust in Indian traditions. There have been debates, interactions, and assimilation of ideas from across philosophies giving a richness and diversity of thought without fear of persecution. Religious clashes of the European world based on ‘truth values’ (I am true and you are false) are almost unknown in India. ‘Philosophy is dead,’ declared scientist Stephen Hawking. In the Indic context, it is relevant perennially ending only with total human freedom.

TRADITIONAL INDIAN PHILOSOPHIES ARE DARSHANAS, NOT SPECULATIVE PHILOSOPHIES

Indian Philosophy often gets the label of ‘speculative philosophy.’ Unlike in science, wherein the scientific proposition has a criterion of physical verifiability, philosophy in the West had a different criterion. It is for this reason that philosophy earned a notoriously bad name in the early years of the twentieth century when the entire field of metaphysics became ‘nonsense.’ The attack against philosophy came from the ‘Analytical Philosophers.’ Hence, in the absence of either empirically verifiable propositions or derivation out of already defined terms, metaphysical statements became meaningless.

Since metaphysics, philosophy, ethics, religion, and aesthetics are all of this nature, the only task that remained for philosophy was that of clarification and analysis. They concluded that the propositions of philosophy are linguistic, not factual, and philosophy was a department of logic. Based on such assertions, Analytical Philosophy swept aside two millennia of lofty human thought into the dustbin of ‘emotive’ thinking. Western philosophy had failed to provide a sound basis for epistemology (theory of knowledge) and it became a complex maze of verbiage that ultimately led to the discrediting of everything metaphysical and of philosophy herself, says Chittaranjan Naik (Apaurusheyatva of the Vedas).

In traditional Indian Philosophy, assertions about the objects of the world ground either in perception or in inference. Hence, there is no scope for these assertions to stray into speculative thought. If they do stray, it is only due to the incorrect application of the pramanas and not due to the nature of the philosophy itself. And when it comes to assertions about things that lie beyond the range of the senses, the assertions ground in Scriptural sentences (Shabda) and in inferences that depend entirely on these scriptural sentences. If they do stray here too, it is again due to an incorrect understanding of the scriptural sentences or the inferences drawn from them. There is a lot of misconception about Indian Philosophy that comes from modern authors, both Indian as well as Western.

Traditional Indian Darshanas are not something derived from basic principles to finally arrive at a conclusion. As Naik says: A Darshana is a Single Vision in which all its elements including epistemology, ontology, metaphysics, the practice, and the fruits of sadhana are like various organs that form a single integral whole. Each of the traditional philosophies or Darshanas is eternal and is part of the Vedic structure. That is why they constitute one of the fourteen branches of learning (vidhyasthanas) known as Chaturdasa Vidyas. ‘Darshana’ strictly is not synonymous with ‘philosophy.’ However, to avoid confusion and when seen as intellectual activity contemplating the world around us, one can broadly consider them as equivalent terms.

NON-VEDIC SCHOOLS

Charvakism or Lokayata: Materialism

Sage Charvak’s ancient Indian tradition, pre-Buddhist and post-Upanishadic, are known mainly from its criticism in later works. For a materialist, only pratyaksha (perception) is the single valid criteria for knowledge. The major criticism against materialism is that despite rejecting inference, implying rejecting generalizations, their own practice in dealing with the world (a generalization that ‘perception and only perception’ is reliable) contradicts that stand. For them, God, souls, heaven, hell, and immortality are non-existent. Matter is the only reality and the world forms by a combination of primordial elements- earth, air, fire, and water; it rejects akasa (ether) as an element. Consciousness is secondary to matter. Nature is enough to explain creation, sustenance, and destruction. Death is the final annihilation with no further births. Of the four Purusharthas, the ends of human life – dharma (right conduct in the broadest sense), artha (wealth), kama (desire), and moksha (liberation), only the pursuit of pleasure and enjoyment of possessions remain sensible ends to life.

Importantly, Charvakism or Lokayata is not the crude hedonism we tend to associate with the materialists. There were certain ethics in that pleasure should not be at the cost of pain and misery. It was also altruistic. They recognized the need for society, law, and order and certainly did not advocate an anarchic society based on an unbridled catering to the senses. The philosophy tempered with self-discipline, intelligence, refined taste, and a genuine capacity for friendship, says Ramakrishna Puligundla (Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy). Amazingly, in Indian society, Charvaks since antiquity had no issues of persecution by the non-Charvaks of any kind.

Jainism

Prince Vardhaman (540 BCE- 468 BCE), twenty-fourth in the line of perfect souls (Tirthamkaras), popularised Jainism and was not its founder. Unlike Buddhism, Jainism stayed in India where it is still a thriving tradition. There are minor doctrinal differences between the two main sects of Jains – the Svetambaras and the Digambaras. The seven principles of Jainism are: Jiva (soul), Ajiva (matter), Asrava (movement of Karma), Bandha (bondage), Samvara (karma-check), Nirjara (falling off Karma), and Moksa (liberation). Jainism is dualistic-pluralism. The two distinct categories of substances- animate (jivas or souls) and inanimate (ajivas or non-souls), make up for its dualism. Pluralism is the infinite number of substances.

The substance (dravya) has either ‘essential’ gunas (eternal and unchanging) or ‘accidental’ paryayas (allowing for impermanence). Hence, both change and permanence are real features of all existence. For example, the ‘soul’ in Jain conception has the essential feature of consciousness and the accidental feature of pain and pleasure. All substances (souls, matter, space, dharma, adharma, and so on) except Time (kala) extend into space. Time is the only ajiva which is infinite and all-pervasive where all things and changes take place. The universe has no beginning or end; it is an endless cycle of creation and destruction.

Souls grade on the sense organs they possess. Plants have only touch and are the lowest; the soul of man has six, including the mind, and is most evolved. The whole universe is thus throbbing with souls. Jiva, the eternal substance with the essential properties of consciousness and knowledge, is atomic and capable of change in magnitude. The sense organs and material body, attaching as karmic particles, are obstacles for the soul (Jiva) to gain primordial omniscience. The goal of life is to remove the limitations of matter and reach the state of pure, perfect, and all-encompassing knowledge. Jainism upholds karma, rebirth, and transmigration of souls. Any soul can achieve liberation by self-effort, discipline, prayer, worship, austerity, simple life, extreme non-violence, compassion, and truthfulness. Jainism rejects God as a creator believing nature is enough to account for the universe. Jainism rejects both the unchanging Brahman of Upanishads or the ‘absolute change’ devoid of anything permanent (Buddhism).

Buddhism

Prince Gautama (563 BCE-486 BCE) following his enlightenment became the Buddha. His teachings form the basis of Buddhist tradition. The rich and vast Buddhist literature divides into many traditions but two are important: the Hinayana in Pali language and the Mahayana in Sanskrit. The core of the former is the Pali Canon, the original teachings of Buddha after his enlightenment. The Four Noble Truths formed the subject of the first sermon Buddha delivered at Benares:

- Life is evil and full of pain and suffering

- The origin of all evil is ignorance (avidya) – not knowing the true nature of the self. The feeling of self as apart from the body-mind complex is false and it is undergoing constant change. Nirvana is cessation of this change. The clinging to the false self is the reason for all misery in life.

- There are twelve links in the ‘chain of causation’ of evil. This chain starts with ignorance leading to a craving. The unfulfilled cravings lead to repeated cycles of rebirth and deaths. Breaking from this karmic chain of repeated lives, one attains a state of serene composure – Nirvana.

- Right knowledge (prajna) is the means of removing evil. Right conduct was a means to right knowledge in the original teaching.

The recommended middle path of Buddha for everyone was devoid of severe austerities. Right conduct (sila), right knowledge (prajna), and right concentration (samadhi) are the most important. The rest five of the ‘Eight-Fold Path’ is for those entering the order of ascetics. Buddhism, spreading to other countries broke up into many schools of thought. Common to the main two creeds is the most important doctrine of momentariness. Everything continues as a series for any length of time giving the illusion of continuity. Regarding differences, Hinayana school was atheistic looking at the Buddha as a human being but divinely gifted; the Mahayana deified Buddha with elaborate worship rituals.

The Mahayana school in turn has two doctrines: the Yogachara and the Madhyamika. The former, akin to the modern subjective idealism, reduces all reality to only thought with no external objective counterpart. Madhyamika is nihilism which denies reality of both the external world and the self too. The Madhyamika school hence maintains the important doctrine of sunya-vada -the ultimate reality is the void or vacuity-in-itself. Hinayana Buddhism and the Yogachara doctrine of Mahayana Buddhism admit to an Absolute Consciousness, a positive ground for all experience. The goal of life would be to merge in this Absolute. The Madhyamika doctrine rejects any positive ground and the goal is annihilation of all illusion into a void. However, the enlightened person (Bodhisattva) still works for the good of society.

VEDIC OR ORTHODOX SCHOOLS

Nyaya-Vaisesika

Nyaya system is the most systematic application of logic in the acquisition of knowledge (epistemology). Vaisesika is an explanation of the reality around us (ontology), beginning with the description of the indestructible atoms as the basis of all reality. Though arising independently, gradually they merged for common study. In its classical form, Nyaya accepted four sources of valid knowledge (perception, inference, comparison, and testimony); the Vaisesika, only two (perception and inference). Gautama (not to be confused with Buddha) founded the Nyaya school in 3rd century BCE; later modifications resulted in the modern school – Navya Nyaya, by Gangesa in 1200 CE.

As the shortest description, Nyaya is logical realism and atomic pluralism. Logic and critical thinking can defend that the physical reality is independent of our awareness not requiring belief, faith, or intuition. Atoms constitute matter and the pluralism stems from the idea there is not one but many entities (material and spiritual) as ultimate constituents of the universe. Nyaya studies philosophy under sixteen categories (padarthas), which includes objects for knowledge (prameyas), the means for knowledge (pramanas), and the purpose of such knowledge.

Thus, the Nyaya system studies the Self; the body; the senses; the objects of the senses; the mind, knowledge, and activity; mental imperfections; rebirth; pleasure and suffering; freedom from suffering; substance; quality; motions; universals (samanya); particulars (visesa); inherence (samavaya); and non-existence (abhava).

Nyaya develops the most elaborate rules of logic for acquisition of knowledge. Indian logic is an instrument for the understanding and discovery of reality quite unlike Western logic- a formal structural inquiry unrelated to the world. The Self is an individual substance- eternal, all pervading, and non-physical; pure consciousness is only an accidental attribute of the Self (unlike Advaita). The aim of Nyaya is liberation of the Self from the bondage and suffering due to its association with the body. Knowledge arising from listening (sravana), intellectual comprehension (manana), and Yogic meditation (nidhidhyasana) leads to cessation of all activity related to the body and thus to liberation. Though there was no focus on God initially, later Nyaya works, especially Udayana’s Nyayakusumanjali, offers proofs for the existence of God from different perspectives including atomism.

Kanada was the founder of Vaisesika system and later authors like Prasastapada and Sridhara wrote commentaries. As old as Jainism and Buddhism, it is also known as the ‘atomistic school’ because of its elaborate atomic theory to explain the universe. However, Vaisesika has a central tenet of particulars (vaisesas) constituting all of existence, out of which some are atomic and some are non-atomic.

Vaisesika, as a philosophy for ontology (explanation of universe), is pluralistic realism. Pluralism, because it holds the universe consisting of a combination of a variety and diversity of irreducible elements. Realism, because it holds reality as independent of our perceptions. Vaisesika recognizes seven padarthas or categories (included in the sixteen of Nyaya) to comprehend the objects making up the world.

Substance (dravya) is the substratum in which qualities and action exist. There are nine ultimate substances in total: five material (earth, water, fire, air, and akasa) and four non-material (space, time, soul, and mind). Material substances except akasa exist as indivisibles called paramanus (atoms), known only through inference. Two atoms combine to form a dyad; three dyads combine to form a triad, the smallest perceptible object. Everything material in the universe is a combination of these triads. Akasa (ether) is non-atomic, all-pervading, and infinite. Only composites made of different combinations of earth, air, fire, and water atoms are perceivable; and being a composite, are transient and impermanent.

The non-material substances – time, space, mind, and soul are indivisible, all-pervading, and eternal. All the non-material substances are known by inference only except the soul known only by direct perception. The most important idea of Vaisesika is the property of ‘particularity’ (or vaisesas) of the indivisible and eternal substances- atoms, akasa, space, time, souls, and minds. This particularity does not extend to composite objects like tables and chairs. Vaisesika also focusses on samayoga and samvaya between two conjoint objects. Samayoga (a book on a table) is temporary, mechanical, external relation between objects coming together when there is no destruction of the components on separation. Samavaya is a conjoint existence of objects, where separation implies destruction of the component objects. Thus, samavaya is necessary, eternal, and internal relation.

Vaisesika maintains the asatkaryavada view of causation- the effect does not pre-exist in the cause. God is co-existent with the eternal atoms and becomes only a designer of the universe by giving a push to these atoms. Hence, atoms and other substances are the material cause of the universe; and God is its efficient cause. Existence is bondage and ignorance where the soul falls prey to desire and passion to identify itself with the non-soul. Like in all other schools, knowledge is the means to freedom and liberation; and the way to break the karmic chain is cessation of action. In contrast to Advaita, the Vaisesika conception of liberation is a state beyond both pleasure and happiness, a substance devoid of any attributes including consciousness. The points of criticism in Vaisesika are its conception of God and the state of the liberated soul.

Samkhya-Yoga

Samkhya, one of the oldest schools pre-dating Buddha, founded by Sage Kapila, influenced all other orthodox and non-orthodox Indian schools significantly. The earliest of the many commentaries is Samkhya-Karika of the 5th century CE. Samkhya philosophy, summarized as dualistic realism, has two equal and ultimate realities: Purusa (Self or spirit), the eternal experiencing subject and Prakriti (matter), the eternal experienced object. Both Samkhya and Yoga recognise three sources of knowledge: perception, inference, and testimony.

Prakriti is the first cause of all objects of the universe including the body, senses, mind, and the intellect. It is uncaused, eternal, all-pervading, and being subtlest – unperceivable; inferred only by its effects. Prakriti, a dynamic mix of three component essences called sattva (purity), rajas (action), and tamas (ignorance and heaviness), manifests as objects of experience (gross or material) for Purusa. Change and activity are the essence of prakriti.

Samkhya holds the satkaryavada theory of causation where the effect is identical with the cause. The three components sattva, rajas, and tamas are present in each object producing pleasure, pain, or indifference in us depending on the relative amount of each component. Dissolution into the primordial cause following evolution of matter leads to cosmic cycles of creation and destruction. The intellect (mahat), ego (ahamkara), and mind (manas) arise in succession from sattva first. This complex is the internal organ or antah-karana, the basis of our mental life.

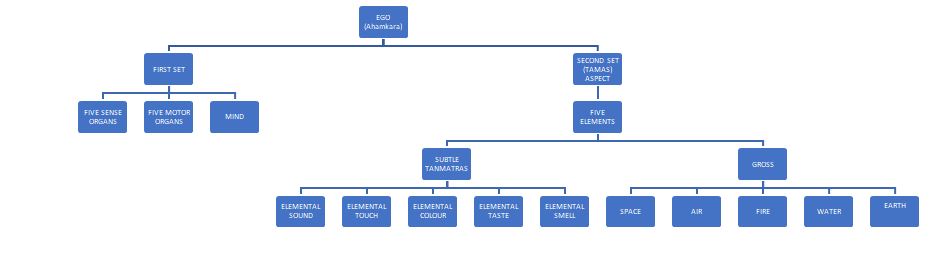

Ahamkara or ego, from which two sets of objects emanate, is the central reason for the entire world. The first set consists of the five sense organs, the five motor organs, and the mind. The second set, emanating from the tamas aspect, comprises five elements that again exist in two forms – subtle and gross. The five subtle elements (tanmatras) give rise to the five gross elements by combinations. The five tanmatras are elemental sound, elemental touch, elemental colour, elemental taste, and elemental smell. Elemental sound gives rise to space; sound and touch combine to form air; sound, touch, and colour combine to form fire; sound, touch, colour, and taste give rise to water; and all five combine to form earth. Depending on the constituent tanmatras, the gross acquires its properties. Evolution and dissolution go on constantly.

Purusa (the Self within), the second ultimate reality, is pure consciousness or sentience separate from the insentient prakriti. Purusa is a pure subject, never an object of our intellect or mind, and whose existence is only by inference. The important argument for the existence of the Self is the most indubitable and incontrovertible experience of one’s own existence. Samkhya believes in the plurality of purusas- a spiritual pluralism. No two humans are mentally and morally identical. Regarding purposes, Samkhya explains by saying that it is ignorance on part of the purusa to get attachment to prakriti; and liberation consists in the knowledge of its absolute and eternal independence from the latter. The liberating knowledge is total independence of the self from the non-self, a state beyond joy and sorrow. Moral perfection is a necessity to achieve this salvation or a state of absolute freedom (kaivalya) from further births. The means of achieving this is through Yoga.

Yoga, as a system of philosophy, closely attaches to Samkhya. Amazingly, despite theoretical differences, all Indian schools, except Charvaka, recommend and recognize Yoga as important means to attain liberation. Yoga differs from Samkhya importantly in the consideration of a Supreme Purusa (or Ishwara, God or the Self) above all the individual selves of Samkhya. The Supreme Purusa guides contact of individual purusa and prakriti to help in the evolution of varying degrees of perfection of purusa. The upper limit of perfection is the Supreme Purusa. Patanjali, not particularly recognizing God in his scheme, however, taught devotion to God for surrendering egoism, the biggest obstacle in the realization of Truth.

Yoga aims for knowledge to free an individual from the shackles of prakriti, most importantly the intellect, mind, and senses. The Yoga-sutras of Patanjali, the first authoritative exposition laying the theoretical and practical foundations, has had many important commentaries later. Yoga has an eight-fold (Astanga-Yoga) path on the route to perfection of an individual. The first five limbs are yama, niyama (control of desires and emotions), asana, pranayama (physical and breath exercises to have a healthy body), and pratyahara (detaching sense organs from the mind). These five are pre-requisites for the further stages of dharana (concentrated focus on limited objects), dhyana (total focus of the mind on a single object). The final stage is Samadhi- the state of pure consciousness where the mind completely dissolves with disappearance of brain-bound intellect.

Can the intuitive knowledge so obtained be a basis for intellectual knowledge, such as that of science? There are two stages again of Samadhi- the savitarka (with its three knowledge components of sabda, artha, and jnana) and the nirvitarka. In the jnana state of the former, knowledge based on perception and reasoning can build conceptual knowledge. In the nirvitarka, the complete Yogi has an instantaneous cognition and complete knowledge of the manifested universe. The state of pure subjectivity is kaivalya or liberation. Yoga is thus a wonderful whole much more than the physical exercises.

There is a needless discussion on whether Yoga is Indian or is it universal like the law of gravity by prominent personalities on both sides of the fence. The confusion mainly arises from the universal application of the asanas and pranayama in achieving the physical health of the human body. In that respect of a narrow domain understanding of a purely physical aspect Yoga definitely is universal and applicable to any human being. But Yoga as a comprehensive philosophy is definitely Indian where its application leads to moksha or liberation. As regards the origin, Yoga is Indian without any compromise and to give examples like gravity is misleading. There is no confusion, the circles of modern western science, about Newton being the one who discovered gravity.

In the next part, we shall review the most important Darshanas- Mimansa and Vedanta, which dominates Indian traditional thinking. We shall also see some important ideas in Indian philosophy and how the so-called antagonism between the orthodox and non-orthodox schools is a figment of overworked imagination arising especially in the western academia.

PART 2

In the first part we saw the basic structure of Indian philosophical systems and how the individual Darshanas compare and contrast with each other. Despite the differences, some points like belief in karma and reincarnation binds all the Darshanas (both the orthodox and non-orthodox) except Charvakism. In this part we shall look at Mimansa and Vedanta which forms the most important component of Indian Darshanas and also discuss the general features of the latter.

Purva-Mimansa and Uttara-Mimansa (Vedanta)

Vedanta, the pinnacle of Indian philosophical thought, literally means the ‘the culmination of the teachings and wisdom of Vedas.’ In terms of historical progression, the earlier schools dealing with rituals (karmakanda) is Purva-Mimansa or simply Mimansa. The later schools with philosophical aspects and speculative thinking (jnanakanda) were Uttara-Mimansa or Vedanta. Purva-Mimansa lays the basis for the pramanas for valid knowledge which Vedanta strictly follows:

- Perception

- Inference

- Testimony

- Comparison

- Postulation

- Non-cognition.

Initially, Vedanta meant only the Upanishads, but later interpretations saw emergence of the three distinct schools of Vedanta. The three main schools of Vedanta are: Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta (most prominent and popular); Ramanuja’s Vishishtadvaita Vedanta; and Madhava’s Dvaita Vedanta.

The Vedas are the oldest scriptures in the history of humanity and may even stretch to before 10,000 BCE according to some scholars. Western Indologists tend to date it much later (mostly after 1500 BCE). Each of the four Vedas (Rig, Sama, Yajur, and Atharva) consist of four parts-Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads. There are 108 known Upanishads of which ten are ‘major’ only because of detailed commentaries on them. It is again a big mistake to describe the later portions as more ‘evolved philosophy’ and the ritualistic early portions as primitive with terms like polytheism, animism, nature worship, or the faulty ‘henotheism’ of Max Mueller.

The Rig Veda conceptualises clearly all existence as a manifestation of a single ultimate reality – indescribable, indeterminate, and absolute; beyond thought and words; and beyond names and forms. The philosophy was well in place right from the beginning; the later Upanishads crystallised and articulated these thoughts. The various interpretations gave rise to many schools over time but with some basic unity in the foundations.

All Upanishads distinguish between a higher knowledge (paravidya) and lower knowledge (aparavidya). The lower knowledge is that of Vedas, phonetics, ceremonials, grammar, etymology, meter, astronomy, and in fact everything in realm of the senses, brain, and intellect. The higher knowledge is non-perceptual, non-conceptual, and intuitive– transcending all three categories of empirical experience; the knower, knowledge, and the known. Moksa, or freedom from ignorance is attainable here and now, where one attains the immortality of no further births. Such an immortality is the state of sat-chit-ananda (pure being, pure consciousness, pure bliss).

Advaita declares Brahman as the sole reality, immanent and transcendent to all creation, as the untiring message of all Upanishads. It is unborn, eternal, and uncreated. The innermost self of every being is Atman; and this is also unborn, uncreated, and eternal. This Atman is separate from the ‘empirical ego’- the idea of the ‘I’ we normally identify ourselves with. The greatest insight of the Advaita is that Atman and Brahman are the same. The Upanishadic wisdom reaches the pinnacle in the mahavakyas or the great statements: tat tvam asi (That thou art), aham brahmasmi (I am Brahman), ayam atma brahma (This Self is Brahman), Prajnanam Brahma (Pure Consciousness is Brahman).

For Advaita, the entire material world is only a superimposition arising out of ignorance (avidya or maya). Maya is the creative power of reality through which the world of variety and multiplicity comes into existence. The phenomenal world is an illusion no doubt, says Shankara, but it is not non-existent nor unreal. The example of the rope and the snake illustrates Shankara’s idea of superimposition. In the darkness of ignorance, the rope is a snake by mistake of the mind; when light flashes, ignorance goes and the rope is immediately recognized in a flash and the snake disappears. Liberating knowledge reveals the true nature of the world as only Brahman (just as light reveals the true nature of the rope).

Brahman and the Atman are the unchanging realities underlying the changing external world and internal appearances respectively. Where all distinctions between the external and internal vanish, the distinction between the Self and the non-Self vanishes and there is an experience of Pure Consciousness. One who does not realise this goes through repeated cycles of births and deaths till the point of realisation. Hence, crucially the illusory world is at the same time real and non-real. Advaita never can degenerate into the false narrative of denying the reality of the world in its entirety and thus stop doing any activity.

God exists in two forms: God with qualities (Saguna-Brahman or Ishwara) and God without qualities (Nirguna Brahman). The former is a personal God while the latter is beyond form and names and is Pure Being, Pure Consciousness, and Pure Bliss. Saguna Brahman is a stepping stone to reach Nirguna Brahman.

Vishishtadvaita (qualified non-dualism) holds three categorical distinctions:

- The support (adhara) and the supported (adheya)

- The controller (niyamaka) and the controlled (niyamya)

- The Lord (shesin) and the servant (sesa).

The first refers to Brahman; the second refers to world. Hence, there are multiple selves in the form of sesas. Reality is like a person; the various selves and material objects are the body, and Brahman its soul. Individual selves and material objects are related to Brahman as parts to a whole. The selves and objects are thus real as parts of an ultimate reality but cannot exist independently of it. The world of phenomena, in contrast to Advaita, is as real as Brahman. God is the Saguna Brahman of Advaita. There are other subtle differences in the schools, but it becomes clear that the individual self of Ramanuja’s Vedanta is not the atman but the empirical ‘I’ of the ego. Liberation, according to Ramanuja, implies an eternal union of a jiva (who has eradicated ignorance) with Brahman to enjoy the highest bliss and infinite glory. The individual identity and consciousness stay intact in this communion, unlike the idea in Advaita.

Dvaita Vedanta, the third school of Madhava, is ‘unqualified dualism.’ Both Brahman and the world are equally and irreducibly different. In Vishishtadvaita Vedanta, selves and material objects are distinctions within Brahman; in contrast, Dvaita Advaita claims the distinction of individual selves and material objects as different from Brahman.

For Shankara,

- Maya manifests Brahman as the world

- It is responsible for the illusory nature of the world

- It is the cause of ignorance in the jiva about his true nature.

Ramanuja treats the world as real but agrees with the first and last positions. Madhava categorically rejects Maya in Dvaita Vedanta. Nirguna Brahman is an absurd idea for both Ramanuja and Madhava. Only the Saguna Brahman, a perfect personality with positive attributes, is the final reality with the power to create, sustain, and destroy the world. Jnana or knowledge is a means to achieve liberation and reach the Brahman state for Shankara; both Ramanuja and Madhava however place bhakti or devotion with total surrender to the divine as the sole means of liberation and uniting with Brahman.

In Advaita, there is loss of individuality in the final state of Moksha. Both Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita disagree by saying that individual consciousness as an independent jiva remains while enjoying the eternal bliss of Brahman. Madhava, in the entire Indian tradition, teaches that God condemns some selves to eternal damnation; and some see similarities with Christian ideas in the propagation of his doctrines.

Vedanta thus has three main schools, but it is generally Advaita Vedanta that is most popular. The philosophy of Shankara has stood the test of time and many Indian savants and saints like Sri Ramana Maharishi, Sri Ramakrishna Paramhansa, Sri Chandrasekhar Saraswati, and Swami Vivekananda generally conform to Advaitic ideas. The three schools are descriptions of the routes of enlightenment and perspectives on the nature of the individual (jiva) with respect to Brahman. There are no differences amongst these three ideas neither on the goal of human life nor in the final state of enlightenment. All flourished with strong individual proponents without any violent frictions.

The gurus stressed that individuals have different temperaments, and hence, the need and evolution of different methods. The goal of Self-realization stays the same. David Frawley says that the simplest definition of Sanatana Dharma is the science and art of Self-Realization. Dvaita philosophies with a personal god as a representation of Brahman and efforts to unite with that god have their echoes in the Abrahamic religions. Hence, generally, Indic traditional systems never had problems with accepting the Christian and Muslim thought. It just added to the diversity.

UNDERSTANDING INDIAN PHILOSOPHIES

Advaita and Buddhism- The Creation of a Clash by The Best European Minds

Koenraad Elst shows that Buddha was every inch a Hindu and his so-called clash with Hinduism is later intellectuals’ fevered imagination. SN Balagangadhara (The Heathen in His Blindness) shows that the supposed clash between Hinduism and Buddhism was a European colonial project simply failing to understand the nature of Indian traditions. Unjustly transposing European ideas to the Indian soil, Buddha became a Martin Luther and Buddhism a Protestant-like attack on Hinduism. Writers after writers successfully made a ‘religion’ of Buddhism rebelling against the tyrannies of ‘Hinduism.’ There were deep flaws in their conceptualisation. As an example, Buddha tried to define the ideal ‘Brahmin’ in his discourses. While rejecting something, one does not try to define the ideal of the rejected. Buddhism had clearer texts and in a rapid time of seventy years in the 19th century, crystallised into a proper religion in Western libraries and institutes. A West, that alone knew what Buddhism was, started judging Buddhism that existed ‘out there.’ Shankara driving out Buddhism with his debates is ignorance on the part of believers of both.

Ignorance for Advaitins is thinking that our senses, intellect, and the phenomenal world is the ultimate reality; for Buddha, ignorance is absent knowledge about the impermanence of everything. Both believe that Karma is a state of bondage due to ignorance, generated by one’s own thoughts, words, and deeds leading to repeated births. Moksha or Nirvana is freedom from ignorance and bondage which one must strive to attain here and now. Most importantly, both agree that Knowledge and Truth are of two kinds – the higher and the lower. The lower is the product of our senses and the intellect applicable to the phenomenal world; and the higher is transcendental; non-conceptual, non-relative, and intuitive. The higher knowledge is soteriological – capable of intense transformation.

With so many common ideas, it is an ignorant notion that Advaita and Buddhism were in opposition. Buddhism spread to other countries due to many factors – royal patronage and the missionary zeal of its monks to name a few. It just receded in the country of origin as people might have continued with their regular traditions. The destruction of Buddhist libraries by invading Muslims helped its demise to some extent too. After the demise of Buddha, Buddhism was divided into many schools and teachings. Regarding some nuanced differences, Advaita claims Brahman to be the unchanging reality. Buddhism however believes there are no eternal entities. The final state of enlightenment is merging in the Brahman for Advaita, whereas Buddhism speaks of Sunyata – silence and nothingness. Hardly a reason for violent or unpleasant encounters with the background of Indian traditions. Finally, it was another tradition that grew in our country with the characteristic of indifference to differences.

Atheism, Time, and Historicity in Indian Philosophies

In Indian traditions, one’s enlightenment is the result of one’s own effort. The discovery that all there is to life is one life or body does not rob an Indian of anything, as Dr. Balagangadhara says. In Indian traditions, ‘atheism’ can also be a way of reaching enlightenment. There is no shock at the claim that ‘God is dead.’ Materialism and atheism were known in Indian traditions since ancient times as Charvakism or Lokayata. Kautilya’s Arthashastra makes a clear mention of this. Western atheism makes no sense to many Indian traditions. Jains, Buddhists, and even some orthodox traditions either reject God or do not demand a belief in God for enlightenment. Most of the Indian traditions are not even ‘theistic’ the way Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are. Indian asuras are not like the devil or his minions in the Bible. Not only do they seek ‘enlightenment’, but some of them are also the biggest bhaktas of our devatas, like a Ravana or a Bali. Indian ‘atheisms,’ ‘asuras,’ or the ‘immorality’ of the devas do not rob Indians of their traditions the way atheism robs a believer in the West. Consequently, without rejecting any piece of knowledge ever learnt, Indians can access the traditions and experiences in a profound way without a belief in God.

Similarly, Indic traditions place time and history as of secondary importance in the realm of the phenomenal world. The higher Truth and reality are beyond time and history and hence, this knowledge becomes timeless and eternal. It is thus futile to try and gain liberating knowledge through history which belongs to the phenomenal world. Thus Mahabharata, Ramayana, Vedas, Upanishads, and all our scriptures are messages permeating across time and generations. The truth about the existence of Rama or Krishna is irrelevant; a major point of divergence from other history-centric religions. Mahabharata and Ramayana may be just imaginations of a talented poet (or many poets as the Indologists would like to believe), but they are real for Indians which is incomprehensible to western culture. The problems arise when the West, rooted in a linear progression of history – from darkness to light, from primitiveness to advancement tries to understand Indian scriptures. History was important in documenting our kings, but it never played a role in dealing with the past; either for intellectuals or the public. From the Indic perspective, for both a theist believing history to be real, and an atheist believing only history to be God; reality will remain elusive.

The Clash Between ‘Science’ and ‘Religion’

The two exclusive features of Hindu traditions and thought are their acceptance of a higher knowledge and a lower knowledge; and that there are no falsehoods. The only purpose of life is the higher knowledge of Reality. The lower knowledge, that of the phenomenal world, in turn, is composed of the body, mind, intellect, space, time, matter, energy, cause, and effect – everything that science deals with. The clear-cut acceptance of the ‘higher’ (para vidya) and ‘lower’ (apara vidya) knowledge never allowed antagonism to science or arts; the latter hence progressed without any fear of persecution. In Indian culture, in one extended spectrum of arts, sciences, spiritual thought, tradition, and philosophy, nothing denied any other; and each was an expression of the others.

In medieval Europe, science was in constant clash with religion; and many times, the scientists compromised to avoid a clash. The clash subtly continues in the western world with an uncomfortable compromise; nowhere more prominent than in evolutionary science. Even today, despite being an educational heavyweight, the US has trouble with the teaching of evolution. Disturbing voices still want alternatives to Darwinism taught in schools – Intelligent design or its older form, God. As late as 1996, the Pope issued a statement in support of evolution, and scientists celebrated this as finally religion seeing reason.

On the other hand, in the last decade of the 19th century when Darwinism was peaking in controversy, Swami Vivekananda simply wondered what the fuss was all about. Evolution is in fact a necessity of matter, he said. There is hardly a western scientist-writer who has spoken about Sri Aurobindo’s deep thoughts on evolution. Indian traditions, temples, and the Brahmanical ‘priests’ never stood in the way of science, astronomy, or even depiction of the most elaborate expressions of sexuality.

Many scientists and physicists in the Western world turn to atheism to do their science. Of course, there were great priest-scientists like Gregor Mendel, but the overall picture is that of antagonism. There were never such issues in India in the so-called ‘secular fields’ of science, technology, medicine, engineering, and others. The divine Goddess could inspire the deepest poetry of Kalidas or the most profound mathematics of Ramanujam. There is also no dichotomy when the chairperson of ISRO breaks a coconut at Tirupati before the launch of high-technology rockets.

INDIAN DARSHANAS: DIVERSE, RICH, AND YET IGNORED

Karl Potter (Presuppositions of India’s philosophies) says: ‘To understand the philosophy of a culture we must come to some understanding of its ultimate values.’ Greek and European philosophers affirm the view that morality, the highest value, lies in the exercise of reason and the subjugation of passions. In contrast, the ultimate value in Indian Darshanas is not morality but freedom and control. It is not rational self-control in the community’s interest, but complete control over one’s environment. Freedom consists of complete liberation from the karmic chains of cause and effect with the achievement of complete peace; and in this life. This freedom is possible for every human being and there is a route for every human, not necessarily the same route. The supreme practical value is renunciation as Krishna tells Arjuna; giving up the fruits of the acts that one is capable of performing successfully.

As Karl Potter notes, the broad classification of non-orthodox and the six orthodox schools is a simplistic division of the huge and rich traditions of India. There were many great philosophers and many individual schools, equally important, with many debates, expositions, commentaries, and criticisms of mainstream schools. Across different philosophies, there were common and differing ideas. Indian philosophical systems have sought answers to most of the existential questions much before western philosophy took its roots in the age of Enlightenment during the 16th to 18th centuries. Even by the time of the Greek philosophers, the basic framework of philosophical thought of India was in place and has remained without many modifications. The narrative of a linear progression of religion followed by its ‘reformation’ and then a rejection of religion itself by science and enlightenment values profoundly fails to make sense in the Indian context. Yet, the phenomenon of ‘colonial consciousness’ has allowed Indians to continue believing that developments particular to European culture could faithfully transpose to Indian soil and explain a completely different culture.

The pre-Socratic philosophers, Socrates, and the later Greeks (like Plato and Aristotle) showed many similar thoughts like Indian philosophers giving credence to the thought that there might have been an interaction. Western philosophy considers itself an inheritor of Greek philosophy but it might have just distorted the views to conform to scientific developments. Indian schools were never antithetical to science, logic, arts, literature, and metaphors when applied to the phenomenal world. The conflict between ‘priests or temples’ and intellectual thoughts is prominently and particularly missing in Indian culture.

Karma and reincarnation are an extremely integral part of Indian thought. The lower and higher truths are important in understanding Indian culture with its rich variety of customs, rituals, gods, and traditions. The greatest strength of Indian culture are the rituals. It was the great genius of our rishis and sages of the past who created a ritual-based society that fulfilled the need for a harmonious society. The entire corpus of Indian thought strives to tell human beings that freedom is possible for everyone; freedom comes by many routes; freedom does not involve stopping any ‘secular’ activity; and freedom never involves a pressure to convert any ‘other’.

Traditional cultures differ from the religious cultures of the west. As Balagangadhara Rao explains in detail (The Heathen In His Blindness), the former roots in ‘rituals’ that bring people together, and where the focus is on performative learning. A huge number of ideas grow in such a culture whose fundamental method of dealing with a differing opinion is indifference. Religious cultures rooted in ‘doctrines’ generally divide people. The focus is on theoretical learning in such cultures and the birth and growth of both atheism and science are on stronger footing here. In such a religious culture, the best it can do to deal with pluralism are ‘acceptances’ and ‘mutual respects.’ But, as Balagangadhara Rao insists, this is not to say one is superior or inferior but the West and the East have different ideas and they stand facing each other as equals. Each has the potential to learn from the other. It is not a one-way street.

Karl Potter says, ‘Very few practising philosophers in India nowadays know the details of the classical systems, and when they do, they know them by rote and not in such a way as to make them relevant to living problems. Yet this is strange, for the aims of classical Indian thought are such as to guarantee the relevance of philosophy to a human predicament and longing which does not change through the ages.’ Any human being with an unfinished purpose of total freedom points to the important fact of Indian traditions that philosophy can never ‘be dead.’

Unfortunately, our schools do not teach us about the rich Indian systems in a perverted application of secularism perhaps; an old European idea that everything related to philosophy in India is religious. Today, these systems have become an area of specialist knowledge for the few interested mostly by accident. Praising it is perceived as an unnecessary glorification of a dead past. As Potter says, it is time that Western professional philosophers – and Indians too, stopped ignoring the contributions of classical Indian thinkers to their pet problems.

APAURUSHEYATVA OF THE VEDAS: A NOTE

Vedic traditions, which have Veda as its central scripture are not based on the revelation of a single Prophet but on the Eternal Word seen by multiple sages – ‘rishis.’ The greatest hindrance we face in grasping the unauthored-ness of the Vedas (apaurusheyatva) is the inability of the mind to form such a conception. Chittaranjan Naik, in a meticulous essay (Apaurusheyatva of the Vedas), discusses the misconception that the Vedas are ‘unauthored’ because there is a failure to know the author. However, tradition says that the Vedas are known to have no human author. The former indicates a failure to know the author, whereas the latter asserts knowledge about its unauthored-ness.

Authoredness, by its nature, is perceptible to the senses whereas unauthored-ness is not. Perception is the wrong means of knowledge (pramana) to know about unauthored-ness. There is a separate pramana in Advaita Vedanta called ‘anupalabdi’ for ascertaining the non-existence of an object. The correct articulation of the traditional position is that the unauthored-ness of Vedas is an object of knowledge and not an absence of knowledge of its author. This knowledge arises from the fact that no author is known despite a beginningless tradition in which the memory of an author would have been known had there been an author.

Naik explains the deep Vedantic idea of words in all forms (from the unmanifest to manifest). Words can exist even if there be no human present in the universe because the principle in which words reside and from which they arise as speech is the eternally existent Consciousness. Just as in a stringed musical instrument where the musical note exists as the ‘unstruck’ note, the ground for the existence of words is the all-pervading and eternal Consciousness.

There are two kinds of proof offered in the Vedic tradition to show that the Vedas are apaurusheya. One is philosophical proof based on Mimamsa. The tradition also offers an alternate proof that does not depend on knowledge of Mimamsa. At first sight, the proof may not appear to be proof at all: it is simply the fact that there happens to be an unbroken tradition that holds the Vedas to be unauthored. But despite its seeming naivety, it is incontrovertible proof. Of course, whether scripture is paurusheya or apaurusheya would make no sense to a person who does not believe in scriptures.

There are three aspects that holds the Vedas to be unauthored.

- Unbrokenness of the tradition

- Etymology of the word ‘rishi’ (‘Rishi’ comes from ‘being a seer’: ‘rishi Darshanath’). So, the very word ‘rishi’ has its origin in the event of ‘seeing,’ of being a drshta (seer) and not a creator of mantra.

- Existence of multiple rishis for the same mantra. The multiplicity of rishis for the same mantras forms the core immune system that guards the tradition of unauthored-ness against counter-claims.

The idea of apaurusheyatva of the Vedas was the prime factor due to which language itself had two categories: the language of the Vedas (Vaidika) and the language of mortals (laukika). The two primary vidyas related to language – Vyakarana (Grammar) and Nirukta (Etymology) had as their fundamental ground the apaurusheyatva of the Vedas. The idea of apaurusheyatva of the Vedas has pervaded all six traditional Darshanas starting from their original texts themselves. This exists in all other branches of learning, and stretches across a vast geographical stretch of land.

The preservation of Sound (the Vedic hymns) in its phonetic and metrical purity is directly based on the special significance of the Vedas as Sruti – the Eternal Sound. The very idea of safeguarding it as a vehicle that carries the Supreme Knowledge grounds in the idea of Vedas as being uncreated, unauthored, perfect, and faultless. What other reason can make so many people in a society or a civilization undertake such onerous tasks as learning to pronounce the Vedas for 10 years or 15 years to protect its purity? And we are not speaking here of a small segment of society, but of a large section of the population stretching across the length and breadth of Bharatvarsha.

One may object by saying that a single dissonant element can rupture this coherency. The onus of proof of a contrary thesis to explain the perceptible and coherent facts has always been with the one who disagrees with the tradition. And no one, so far, has provided such contrary proof. Thus, the conclusion that the Vedas are eternal, beginningless, and Apaurusheya is from the facts that there exists an extensive tradition of the Vedas being ‘handed down’; the tradition forms a tightly coupled coherent system in which one cannot deny a single element without throwing the onus of proof on to the denier; and any alternate hypothesis needs rejection on the law of parsimony.

In the next section, we shall see how Indian Darshanas explain the process of perception and reality of the world around us. These significantly differ from the western ideas of the description of the world around us. The two systems also differ in dealing with the trickiest problem of consciousness. For Indian philosophy, it is a primary entity with varying relations to the material world. For western philosophies, it is generally a secondary entity arising from the matter.

PART 3

CONSCIOUSNESS, PERCEPTION, AND DESCRIPTION OF REALITY

INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN A NUTSHELL

In the previous parts 1 and 2, we have seen a gross description of the Indian philosophical systems (or Darshanas) and how they generally differ from the western philosophies. In the next section, we shall see how Indian systems, focussing especially on Advaitic Vedanta, deals with the descriptions of reality of the world around us and on the tricky subject of consciousness. The subsequent parts rest primarily on the seminal book of Chittaranjan Naik (Natural Realism and The Contact Theory of Perception).

Western philosophy in explaining perception starts with the objects of the world. For vision; light falls on the objects and is reflected by said objects to reach the retina. The generated neural impulses then reach the brain where an image forms. It is a mystery, however, how an internal image projects as an ‘outside’ world. Similar to other sensations – hearing, taste, smell, and touch, our brains reconstruct the world after receiving the data through our senses.

The finite speed of light ensures that what we perceive is no longer an instant picture of the world. The more distant the object, the farther back in time our object of perception. Humans will know about a suddenly disappearing Sun only after about 8 minutes, the time taken for light to travel from the Sun to Earth. Furthermore, we never know the actual state of reality since our perception is a brain construction – an indirect realism. Thus, all the objects in the world have two components- a ‘noumenon’ (the original, forever beyond our comprehension) and the ‘phenomenon’ (the representation in our brain of the world). Hence, in terms of ontology – the reality of the world, the real and actual is always unknown.

The sense of ‘I’, is the ‘consciousness’ that allows us to participate in the world and gives us a sense of doership. The classic western paradigm of consciousness is the state of awareness beginning after waking up from a dreamless sleep and continuing till going back to sleep again, or slipping into a coma, or dying. It excludes deep dreamless sleep. Dreams and ‘self-awareness’ are special forms of consciousness. The overwhelming western paradigm is that consciousness is a product of the mind.

Indian philosophy has a completely different take on perception and consciousness. There is an incommensurability problem when western paradigms try to understand Indian philosophy through their frameworks of understanding.

CONSCIOUSNESS AND COMPUTATION

‘Who is the I in the I?’

Consciousness studies have become respectable science now with the application of the latest in technology. The biggest mystery is how brain processes, involving 100 billion neurons and 50 trillion synapses, can give rise to consciousness – a unified, well-ordered, coherent, inner subjective state of awareness in response to multiple stimuli of all sorts. There are three main problems of the soul, mind, and matter in philosophy. The west rejects the soul; all discussions are about the properties and interrelation between mind and matter.

The dualists believe that the mind and the body (matter) are fundamentally two different phenomena. In contrast, the ‘monists’ hold that there is only one source of origin giving rise to the other; either mental alone (‘idealist’ monists), or physical alone (‘materialist’ monists). The overwhelming contemporary scientific-philosophic view favours the ‘materialist monist’ theory. Thus the mental stuff, including consciousness, comes from the realm of physical stuff. Matter organizes itself into higher orders of complexity leading to life, bodies, mind, intelligence, and finally consciousness. By logical extension, a computer can lead to consciousness too. This is the basis for Artificial Intelligence (AI) machines.

As John Searle explains in his wonderful book (The Mystery of Consciousness), the strong debate amongst scientists and philosophers between computation and consciousness takes four positions:

- Strong AI (Artificial Intelligence): A computational process entirely generates consciousness

- Weak AI: Brain processes cause consciousness. A computer can simulate the processes but does not generate consciousness.

- Brain causes consciousness; there can be no simulation computationally.

- Consciousness is a complete mystery.

The first two have the strongest proponents. The strong AI model contends that the implemented program, by itself, guarantees a mental life. There is no first-person inner state at all. Everything boils down to stimulus inputs, discriminative states, and reactive dispositions hanging together in a computer-like brain of ours, and consciousness is a certain type of software of the brain. The weak AI model says that the computer program can give near-perfect answers to questions but does not understand the meaning of the answers at all. Consciousness gives internal, subjective meaning to answers. Programs are entirely syntactical having rules, principles, and processes; minds have semantics with meanings. Syntax is different from semantics.

ONTOLOGY AND PERCEPTION IN WESTERN PHILOSOPHY

Ontology (‘onto’- real; ‘logia’ – science) studies what is real and what exists; the fundamental parts of the world and their relation to each other. The standard Western paradigm is the ‘stimulus-response theory of perception,’ a stimulus (light, sound, smell, taste, touch) evoking an inside brain response through an intermediate causal chain. This is also Representationalism – the perceived world as an internal representation of an external world; hence, an indirect form of reality.

In Kantian philosophy, the original unknown is the ‘noumenon’ (in modern parlance – the ‘non-linguistic’ world) and the known constructed reality is the ‘phenomenon.’ This is the contemporary scientific and philosophical view and gets the terms ‘Scientific Realism’ or ‘Indirect Realism.’ The world being a construction in the observer’s mind is thus mind-dependent. What we perceive are secondary qualities as presented to our sensory faculties and their specific powers. They are not the primary qualities that belong to the objects themselves. All Representationalist systems cannot thus effectively address the topic of ontology (reality) as the real world (noumenon) is always beyond our capacity of comprehension.

A stimulus-response system from the external object to the mind is incoherent in explaining the reality of the world. There is an assumption that the intervening medium, space, time, and their relations carrying data to the sense organs are all noumena; actually, they more logically fit into the category of phenomena. Every object in the causal chain from the external world to the perceiver, including the intervening medium, sense organs, and the final brain becomes a ‘phenomenon’ and have an unknown ‘noumenon realm.’ This logical extension of the current thinking questioning the truth status of the body and the sense organs leads to conundrums and inconsistencies. The stimulus-response theory of perception presents a riddle – what is the actual reality? This problem is unresolved to this day despite untiring efforts.

There have been attempts to develop a Direct Realism theory in western traditions saying that there is no transformation by the intervening medium. Somehow, we experience the world directly ‘as it exists.’ However, these positions do not reject the scientific principle of reflected light on matter reaching our senses and the brain converting the neural data. Problematically, the scientific paradigm of data reaching our brain and then undergoing transformation is perfectly incompatible with Direct Realism. One either rejects science or rejects Direct Realism finally in the western philosophical traditions.

PERCEPTION AND ONTOLOGY: THE COUNTER-NARRATIVE OF INDIAN PHILOSOPHY AND THE PROBLEM OF INCOMMENSURABILITY

Indian traditions have a completely different take on consciousness, perception, and ontology. This has been the consistent view of all the philosophical systems across thousands of years with a few minor variations. The major principles of the Indian philosophical stand are:

- The Self is a primary substance in Indian traditions with consciousness as its essential attribute and with a subjective notion of ‘self-awareness.’ An empirical criterion cannot verify the existence of this Self. The knowledge comes from Sabda-pramana; inference from the words of an authority, the Vedas here. The Self as a distinct substance resolves the perplexing problem in establishing a coherent ontology (reality) of the world. Thus, perception is of ‘real’ objects only, since the self-effulgent consciousness is a ‘revealer’ of objects. It is like light in revealing objects but the analogy is not completely correct as even light comes under the category of objects.

- Direct Realism states that there the two entities in perception – the Self and the physical organs of the body, in their respective roles as the primary cause and occasioning cause. The physical processes of the body do not cause transformations in the percept. The sense organs give only a transparency to the Self in the experience of the world.

- There is a dissolution of the artificial reality-divide, in the form of the phenomenal and the noumenal because all objects are namable and knowable.

- Entities are fundamentally of two kinds: sentient purusha (soul) and inert prakriti (mind and matter) clearing the confusion to the meanings of the three terms used in philosophical discourse: ‘soul,’ ‘mind’ and ‘matter.’

- The mind and matter are the same appearing in two different modes of presentations. This explains the correspondence between concepts appearing in the mind and objects appearing in the physical world in a lucid manner without resorting to reduction of one to the other.

- Importantly, the object that appears in the mind is universal while the object appearing in the world is an individual object. The universal maintains the word reference under all conditions. For, when we refer to Devadatta, what exists in the mind is the universal Devadattahood; and hence, even though Devadatta changes in time from being a child to a youth to a toothless old man, the name would refer to the same person.

- Objects of the world are mind-independent because their existence, not determined by the individual self, is public. An independent object should be available for perception and interaction by other individual beings. This distinguishes a valid perception from an illusion or hallucination. Thus, material processes are real and reality exists independent of the observer.

DIRECT REALISM OF INDIAN TRADITIONS

Most systems of Indian philosophy have only one clear stand of ‘Natural Realism’ or ‘Direct Realism.’ This is an active ‘contact theory of perception’ where the perceiver (central in the scheme) goes out, contacts the object in the external world to gain direct information about the world as it exists. The external world experienced is an actual world in its reality and not a construction. Direct Realism, to reiterate, is the experience of the objects in an instantaneous and direct manner without any transformations of the intervening medium. Thus, pratyaksha or direct perception is a valid pramaana or means of knowledge. In Western traditions, perception is never a valid source of knowledge as the world remains unknown in its reality.

Thus, Indian philosophy gives an alternative explanation to reality. The reasonings of western paradigms are not applicable in proving or disproving the Indian view – the problem of incommensurability. Representationalism (Indirect Realism) is altogether absent. In Indian philosophy; the closest it has come to is the Sautantrika school of Buddhism. For western traditions honouring science, Indian paradigms do seem difficult to digest or understand. However, the latter has far more important consequences, even leading to enlightenment (moksha, liberation, or salvation) – the highest ideal. In Indian traditions, a belief in a personal God is not a mandatory requirement for liberation. Amazingly, in Indian traditions, ‘philosophy’ is not an independent exercise, but intricately weaves itself into the fabric of both science and tradition.

THE PRAMANAS AND THE NATURE OF THE PRAMEYAS

All traditional Darshanas begin with an explanation of the pramanas. A pramana is a means of obtaining knowledge about an object. There are three basic pramanas in traditional Indian Philosophies. They are Agama or Sabda (Scripture), pratyaksha (perception), and anumana (inference). The object known by means of a pramana is the prameya. The knowledge of the object is prama. Knowledge of an object is not a distinct entity that stands between the subject and the object but a qualification of the subject or the knower.

Now, there is a distinct mark of the prameya, or object, in traditional Indian philosophies that is missing in Science and Western philosophy. This mark is the mark of ‘being seen’ or the mark of ‘knowableness.’ This point is so vital that if we fail to recognize it, it is likely to lead us into such a position that we would not be speaking Indian Philosophy at all. The mark of ‘being seen’ is a mark of prakriti. This feature of objects being ‘the seen’ finds expression in the philosophical tenet that there is a contact between the seer and the seen object – sannikrishna. The form that the (reflected) consciousness of the seer assumes in seeing the object is ‘vritti.’ Thus, the entire world, directly seen ‘as it is’ has no extraneous mediating factor between the seer and the seen.

SABDA (AGAMA OR SCRIPTURE) AS VERBAL AUTHORITY

Testimony from reliable authorities (Sabda) is a routine way we acquire knowledge in the material or the laukika world. When a high school student accepts Newtonian equations or Einsteinian physics as valid after reading the textbooks, it is sabda in a way as a means for acquiring knowledge. However, the world also shows the means by which the student can actually confirm or deny these equations by way of a channelised education and individualised efforts.

In Indian orthodox Darshanas, sabda as a verbal testimony applies specifically to the alaukika sphere which claims the existence of Brahman. However, like in the laukika sphere which gives the means to confirm the verbal statements of authorities, the Indian Darshanas show the way (Yoga, meditation, and other practices) to confirm the existence of Brahman and achieve liberation. The non-orthodox schools like Buddhism and Jainism accept Yoga and meditation practices as a route to achieve liberation despite denying the existence of Brahman. The problem mainly arises when critics do not want to subject themselves to the means and yet proclaim that these statements from the Vedic seers have no validity. Assertions of any kind should also declare the means by which one can confirm or deny the assertion. These, Indian Darshanas offer plenty and hence ‘sabda’ as testimony is never a statement that one needs to accept in blind faith.

DIRECT REALISM OF INDIAN PHILOSOPHIES VERSUS THE INDIRECT REALISM OF MODERN CONTEMPORARY WESTERN PHILOSOPHIES

Indian philosophy for thousands of years has been clear on its stand of a ‘Natural Realism’ or ‘Direct Realism.’ Hence, the external world as seen or heard is an actual world in its reality and not a construction. Perception is never a valid source of knowledge in western traditions but it is the most important source of knowledge in Indian traditions. Perception involves transparency between the self and the object and contact between the two. There is no time lag in perception. The physical organs are only to enable this transparency and work as seats of experience too. Perception, an inside-to-outside process, is thus a composite process in which the self, the mind, and the sense organs together participate to establish contact with the object.