“A democracy is a government of all by a majority of proletarians; a soviet, a government by a small group of proletarians; and a dictatorship, a government by a single proletarian. In the traditional and unanimous society there is a government by a hereditary aristocracy, the function of which is to maintain an existing order, based on eternal principles, rather than to impose the views or arbitrary will (in the most technical sense of the words, a tyrannical will) of any “party” or “interest.” The “liberal” theory of class warfare takes it for granted that there can be no common interest of different classes, which must oppress or be oppressed by one another; the classical theories of government are based on a concept of impartial justice. What majority rule means in practice is a government in terms of an unstable “balance of power”; and this involves a kind of internal warfare that corresponds exactly to the international wars that result from the effort to maintain balances of power on a still larger scale.”

Ananda Coomaraswamy in “Primitive Mentality” (The Essential Ananda K. Coomaraswamy)

FIRST PUBLISHED AS A 4-PART SERIES IN PRAGYATA ONLINE MAGAZINE. LINKS PROVIDED IN THE END.

PART 1

Political Ideologies – A Dummy’s Understanding of Background Western Theories

Introduction

India’s ancient and mediaeval political history was largely absent from public consciousness during colonial rule. Post-independence, India continued with English political ideas. People in power after independence, undoubtedly with a deep love for the country, were mostly products of Western education and training. Their modernization philosophy looked with disdain at traditional India. The Orientalist view of a past decadent India, partially corrected by the British, was the prevalent attitude, which is now embedded deeply into our collective psyche as colonial consciousness.

Bhikhu Parekh (The Poverty of Indian Political Theory) wonders how a rich Indian tradition, with great philosophies and intellectual freedom, could not throw up an indigenous political theory for self-rule. Indian thinkers were not completely enamoured by Western political thought. Sri Aurobindo believed that India’s future should root in its own ethos, and a blind aping of European ideals in terms of politics, administration, morals, ethics, and law would be a recipe for disaster. We had a character of our own; foreign rule destroyed our shell, but the core was still intact. He was critical of both the parliamentary system of European democracy and that of Russian socialism, or communism.

The power structures completely ignored all such thinkers.

After independence, due to a series of political machinations, a Marxist ideology gained control of the narrative of India, which distorted the situation even more. The country came out of the grips of the monotheistic influences of Islam, Christianity, and some form of Marxism when, in 2014, the BJP took hold of the country. This reactionary and ‘right-wing Hindu’ political gain may provoke hostilities even more than before.

Let us first look briefly at what politics and ideology mean at the popular level of discourse. Later, we shall see how these political theories may have a limited application to India; they may even be dangerous.

Forms of Government

The simplest definition of a government is a system governing an organised community, commonly a nation (a group of people with some commonalities) or a state (a geographical area belonging to a nation of people). The nation-state is now a unified notion. The legislature, executive, and judiciary form the three estates of the government.

In India, the legislature is the Parliament with its two houses: the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha. The legislature makes laws and elects the Prime Minister, the President, and members of the executive. The President, the Vice President, and the Council of Ministers, with the Prime Minister as its head, form the Executive Union in the traditional definition. In a broader sense, it also includes the non-political permanent civil service office. The powerful executive gives shape to and implements the legislative laws reflecting the government’s policies.

The Judiciary consists of the judicial system’s network, starting with the Supreme Court. This system interprets and applies the law in the name of the state; it is an important mechanism to maintain law and order and settle disputes of any form at any level, from the individual to the collective. The judiciary cannot make laws (legislative responsibility) or enforce laws (executive responsibility). Through judicial review, however, it can change or modify laws. The three interdependent, yet independent, estates create enough checks and balances to prevent faulty ideas and people from damaging the country.

Why do governments exist?

As one author (Anne-Marie Slaughter) elaborates, the most important is the protection of its citizens from physical, mental, and intellectual violence, either inside or outside the country. This idea of a protector requires taxes to equip an army and a police force, to build courts and jails, and to elect or appoint officials to pass and implement the laws. Next, the government is a provider of goods and services that individuals cannot provide for themselves. This ranges from infrastructure building to creating a welfare state policy for challenged citizens like those in old age, sickness, disability, and unemployment. The final role of the government is to encourage citizen capabilities by investing in areas like education and nurturing talent to meet economic, security, scientific, demographic, and environmental challenges for the country.

An ideal government ensures freedom of expression, the rule of law, equality of opportunity, and the integrity of the country. Political thinkers across centuries struggled to decide the best form of running the country by the ‘wisest and the best.’ Is it democracy (an ideal norm today), monarchy (single-person hereditary rule), oligarchy (a group of people distinguished by nobility, wealth, education, and holding equal powers), autocracy (strong central party or military power monarchical or oligarchic in nature), or totalitarianism (extreme control)? Generally, as power concentrates more in the ruling elite, the citizen’s power reduces. What is the golden balance?

Some Philosophers on Democracy

Democracy is the best form of government, according to popular, academic, and intellectual opinion. However, thinkers across centuries raised problems with democracy and believed that it was not indeed a good method of administering the country. Will Durant (The Story of Philosophy) discusses many philosophers critical of democracy.

Plato (4th century BCE) could not think of democracy as an ideal form of governance. Plato believed that every form of government tends to perish in excess of its basic principle: aristocracy by limiting too narrowly within power circles; oligarchy by the scramble for wealth. Following a revolution, democracy arrives and gives people an equal share of freedom and power. But even democracy ruins itself in excess of its basic principle of an equal right for all to hold office and determine public policy. However, Plato says people lack the education to select the best and wisest rulers. Oratory skills and the ability to garner votes become more important to winning power than ability, even as nepotism, corruption, and general incompetence become widespread in a democracy. The upshot of such a democracy is tyranny.

For Plato, the ideal was a democratic aristocracy where everybody has an equal opportunity to reach the seat of power as ‘philosopher-kings’, without the hypocrisy of voting.

Plato’s pupil Aristotle also thought government was too complex a thing to have its issues decided by numbers rather than knowledge and ability. For Aristotle, democracy has a false assumption that those who are equal in one respect (like the law) are equal in all respects, including governing. Aristotle scathingly says that in a democracy, ability sacrifices itself to number, while trickery manipulates numbers.

In Francis Bacon’s ideal world, the government is of and for the people, but by the ‘selected best’ of the people. Similarly, Spinoza also wanted to limit office to men of ‘trained skill.’ He thought that democratic governments had become a procession of brief-lived demagogues, with men of worth avoiding political office. Spinoza was clear that, despite being a reasonable option, democracy still had to solve the problem of selecting the ‘wisest and the best’ to rule themselves. Freidrich Nietzsche, a German philosopher who observed forms of government, believed that the ideal society divides into three classes: producers (farmers, proletaries, and businessmen), officials (soldiers and functionaries), and rulers. Like Plato, he believed philosophers were the highest men.

Importantly, the best intellectuals of the Western world, from Socrates down to the contemporary period, were acutely aware of the problems with democracy. Yet, over the centuries, through revolutions, public opinion, and emotions, it has become the norm — an “ought to” — all over the world. The major issue is the balance between individual rights and government rights, with the extreme ends being anarchism and totalitarianism, respectively. The golden mean is apparently democracy today.

Political Ideologies in The Modern World: Left, Right, and Centre

Political Ideologies by Andrew Heywood is a wonderful resource for giving a basic understanding of political ideologies. Though the exact definition of a political ideology is elusive, it can mean: a) a political belief system; b) an action-oriented set of ideas; c) the ideas of the ruling class; d) ideas that generate a sense of collective belonging; e) a doctrine that claims a monopoly of truth. All ‘isms’ finally try to balance individual rights and state rights. Practically, the citizen would want the freedom to pursue desires, acquire property, and seek happiness without state interference. The citizen would also want strong protection for individual pursuits from the state.

‘Left’ and ‘Right’ date to the French Revolution (late 18th century), when a legislature replaced the aristocracy. In the seating arrangement, members of the aristocracy supporting the king sat on his right, while ordinary members sat on his left. Gradually, the term “right” began to mean ‘monarchist’ or ‘reactionary’ to retain an old order, and “left” began to imply ‘revolutionary’ tendencies with egalitarian motives.

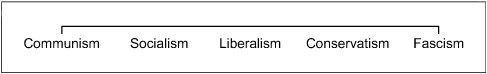

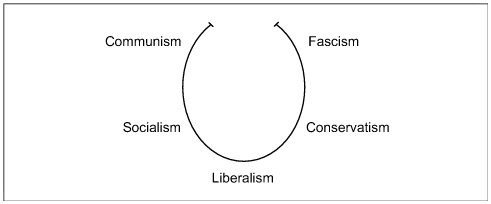

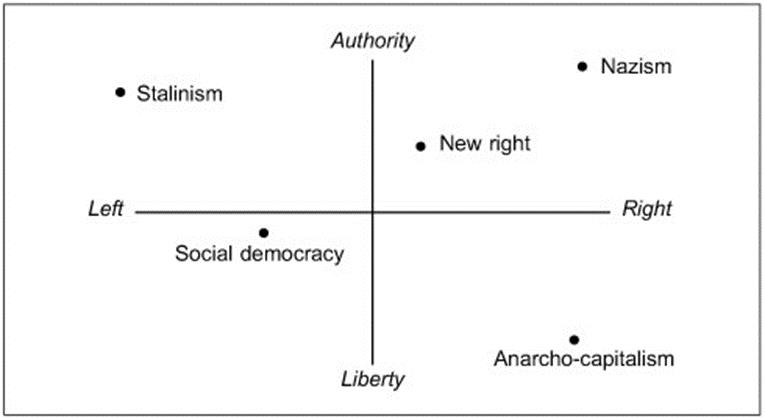

The left and right wing, in popular understanding, differ in dealing with two aspects: individual policy and economic policy. The left allegedly would want equality for all and a centrally planned economy with desirable collective ownership. The right, again allegedly, would believe equality is impossible and that the best economy is free-market capitalism. There are any number of intermediate positions. Some represent the political spectrum as horseshoe-shaped because the extremes of communism and fascism become similarly ‘totalitarian’. The pictorial representations only simplify the understanding; at a practical level, governments tend to be complex combinations. Feminism, environmentalism, and animal rights activism now make for a heady mix as they enter political discourses.

Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism: The Traditional Right, Center, and Left

Liberalism, an outcome of Western industrialization in the late 19th century, came with the Constitution and democracy. Classical liberalism implies an individual with the maximum possible freedom. The state only maintains domestic order and personal security with minimal interference in the economic policies of a self-regulating free market. Modern liberalism (social or welfare liberalism) gives the state more powers to prevent unbridled capitalism.

Conservatism, traditionally placed on the ‘right side’ of ‘central’ liberals, tries to preserve the traditional order and resist change. It attempts to respect the accumulated wisdom of past individuals, institutions, and scriptures. Change is not a revolution but a gradual, organic, traditionally rooted, and debated evolution. There are various forms of conservatism: authoritarian conservatism (strong authority from above establishing order); paternalistic conservatism (a more prudent version of strict authority); and libertarian conservatism (advocating free-market laissez-faire liberalism but with a central authority). Adopting a more welfare-state approach, conservatism could garner public support in democracies. Conservatives essentially say that experience and history guide future political action rather than abstract principles of freedom, equality, and justice. The continuous criticism against conservatism has been that attempts to preserve the status quo are for the sake of the dominant elite’s interests.

Socialism, where the collective subsumes the individual, opposes capitalism. Social interaction and membership in collective bodies make cooperation more important than competition. Each person ‘works to the best of their ability, and each gets as per the needs’ by the state. The state attempts egalitarianism — a society of equals. The industrial capitalism of Europe, giving rise to a hugely disadvantaged and poor working class, originated socialistic ideas against the exploitative principles of a free-market economy.

However, a simple core philosophy has diverse traditions. Utopian socialism argues on moral grounds for allowing more compassion between human beings. Scientific socialism is a scientific Marxian analysis of historical and social developments, predicting that ‘socialism’ would inevitably replace ‘capitalism’.

Regarding the means, revolutionary socialism propagates revolution, throwing out the existing political order. Reformist or democratic socialism believes in the parliamentary system and basic liberal democratic principles such as constitutionalism.

As to the final ends, fundamentalist socialism (Marxists and Communists) attempts to completely replace the capitalist systems with common ownership, and revisionist socialism aims to reform capitalism as a balance between the moral aspects of socialism and a more liberated economy. India after independence was an example of democratic or revisionist socialism. Socialism with deep state control invariably tends to stifle individual freedom and liberty.

Communism takes a stricter stance against capitalism, preferably through a revolution. For them, society consists of two classes: the bourgeois and the working proletariat. Marx believed that in the ultimate struggle between the two classes, the proletariat invariably wins over the hegemonic class to create a new classless society. The economy would exist without private ownership. Trying to distinguish between socialism and communism might seem a bit difficult. In the early phases, socialism aimed to socialise production only, while communism aimed to socialise both production and consumption. Traditional Marxists employed the word socialism in place of communism. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, socialism became an intermediate term between capitalism and communism.

Russia and China are traditional socialistic-communistic countries, but they have their own criticisms. The Russian Lenin and Stalin forms of communism were more state-controlled capitalism and single-party rule, leading to totalitarianism. The economic model of China appears to pay only lip service to Marxist or communist principles. Religion, family, and traditional social structures that bind individuals take a secondary role in the socialist or communist way of thinking. Traditionally, people consider communists to be atheists. In the latter part of the 20th century, communism collapsed in Eastern European countries.

Other Political Philosophies

Most political ideologies are a variable mix of the three main forms, but there are other forms of some relevance too. Nationalism, believing that the nation (group of people) is the central political principle, has many forms:

a) ‘classical’ political nationalism uses common bonds like culture, ethnicity, religion, language, and traditions;

b) liberal nationalism with a right to self-determination;

c) conservative nationalism defending traditional values and institutions; and

d) expansionist nationalism, exemplified by colonial Europe, an aggressive form of nationalism.

Expansionist nationalism, in turn, ironically brought anticolonial nationalism to Africa and Asia. Nationalism subsumes the individual for the sake of the larger, but the underlying character has ranged from extreme left to extreme right in its thinking.

Feminism, a relatively contemporary ideology, seeks to address the social role of women and their subjugation to men in most societies. It is a transnational movement seeking political, social, economic, and cultural equality with men. There are many forms of feminism: liberal, socialist, and radical feminism previously; eco-feminism, black feminism, and postmodern feminism more recently. The first wave of feminism in the mid-19th century was about universal voting rights. The second wave, a century later, was a more vociferous demand for equal rights. The third wave emerged in the mid-1990s in the developed world, seeking to modify perceptions of gender as a continuum rather than a strict binary of male and female. Gender identity and its expression became independent of biological sex. Feminism has exposed gender biases in the social, political, and domestic worlds sharply, and there have been many reforms in the Western world. However, people now talk about the collapse of feminism and a post-feministic world because of internal differences and its restricted western relevance, according to some.

Fascism, a fashionable word to use for many politically powerful people, thankfully remains within the confines of history (the period between the two world wars) and not contemporary society. The philosophy of fascism would be ‘everything for the state; nothing against the state; nothing outside the state‘. The definition of fascism has been based on what it opposes, a reason for its contemporary broad application to people and parties; it can thus be anti-rational, anti-liberal, anti-conservative, anti-capitalist, anti-bourgeois, or anti-communist.

Italian Fascism under Mussolini (1924–23) was an extreme statism based upon unquestioning loyalty towards a ‘totalitarian’ state. Hitler’s Nazi dictatorship in Germany was another manifestation of fascism, but some view fascism and Nazism as distinct ideologies. Nazism based itself on Aryan supremacy theories and virulent anti-Semitism, which led to great genocides. Neo-fascism, or ‘democratic fascism’, a contradiction of terms, stays away from totalitarianism and overt racialism but concerns itself with anti-immigration campaigns and a hyper-nationalism against globalisation.

Anarchism is an individualistic philosophy with a complete rejection of any form of government, basing itself on human goodness and love rather than any form of top-down control. It does not have a place in any country’s governance, thankfully, but some of its principles have given important insights into issues like individual liberty, ecology, transport, urban development, consumerism, new technology, and sexual relations, says Andrew Heywood (Political Ideologies).

Postmodernity and Globalisation in the Contemporary World

According to social theories, the ‘core’ political ideologies of liberalism, conservatism, and socialism arose in response to modernization. This modernization had social (dominant middle and working classes), political (constitutional democracies replacing monarchical absolutism), and cultural (commitment to reason and progress) dimensions. Post-modern societies replace class, religious, and ethnic values with intense individualism, leading to movements like feminism, gay rights movements, and environmentalism. Similarly, globalisation created a borderless world, challenging political nationalism. Globalisation also becomes the new imperialism to resist and revolt against, and hence, religious fundamentalism also arises as an opposing force.

The contemporary world has gravitated towards a liberal democracy as some sort of norm. Liberalism, at its core, demands individual freedom to practise its values without interference from the state. The state must remain neutral between all opposing camps without favouring any group. This is the liberalism that was the basis of secularism in European nations.

Bashing the Left

Roger Scruton (Fools, Frauds, and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left) criticises the left thinkers who understand every aspect of historical, social, economic, legal, and civic life as class struggles between the bourgeoisie (controlling the means of production) and the proletariat (in control of labour). There is silence when the realities do come up, like with Stalin or Mao. Marxist studies conclude that the production of material goods is the real motor of social change, a misleading account of modern history in which legal and political innovation have often been the cause of economic change, says Scruton.

The exploiter and exploited paradigms explain any historical, political, social, and economic turmoil; an example is the dubious Aryan-Dravidian discourse in the Indian context. Scruton says, ‘Marxist history means rewriting history with class at the top of the agenda. And it involves demonizing the upper class and romanticizing the lower.’

In different countries, the left has had different agendas: consumerism, gay rights, human rights, women’s rights, eco-rights, and so on, but the revolutions never clearly spell out the alternatives. The left thinkers, random and obscure, sometimes clothe their language in a pseudo-mathematical language. Scruton speaks of a prominent thinker, Dworkin, who argues that the right to speech exists to protect the dignity of dissenters. Thus, remarkably, a truly sincere government, after having passed a law, should be lenient towards those who disobey it!

Thomas J. DiLorenzo (The Problem with Socialism) claims that everything is wrong with socialism. Free education, healthcare, and houses as a right without the need to work are indeed attractive, but someone must pay for them. These are the taxes that only hide the cost. Every single tax payer works a third of the year in the USA to pay all the taxes owed to the state machinery. Soviet Russia, Chile, Argentina, the democratic ‘Fabian’ socialism of Britain, Argentina, the Nehru-Mahanalobis five-year plans of post-Independent India, and China before opening are all examples of socialistic administrations destroying the country’s economic fabric. Totalitarian, socialistic countries like Russia were disasters for personal freedom and liberty. A lack of incentive to work, central planning ignoring local intricate market forces at work, and bureaucratic plans replacing rational economic plans are the main reasons for the worldwide disaster of a socialistic economy.

Egalitarianism looks good in theory, but human beings are unequal in talent and merit. Islands of socialism in the form of government enterprises like schools, libraries, post offices, railways, banks, police, and so on have always been loss-making bodies across the world, says DiLorenzo. Socialists throughout history have stood on a negative programme of ‘hatred of an enemy or envy for the better off’. The enemies could be the aristocrats, Christians, capitalists in Russia, Jews in Germany and Austria, plutocrats in Europe, and ‘Wall Street’ or the wealthy ‘one percent’ in the USA. To a socialist, the ends justify the means, which is the reverse of traditional morality and can hence justify any action desired by the socialist.

Death counts, up to 100 million in the 20th century, have been the highest under socialist regimes the world over, as the ‘The Black Book of Communism’ catalogues them. DiLorenzo says that intellectuals prefer to pontificate that socialism, an ideology associated with the worst crimes, the greatest mass slaughters, and the most totalitarian regimes ever; is more compassionate and humane than free market capitalism. The latter alleviated poverty more, created more wealth, provided more opportunities for development, and supported human freedom more than any other economic system in the history of the world.

Welfare programmes in socialism have the defining moral hazard that the benefits destroy the incentive to find a job and become financially independent. In the USA, welfare programmes since the late 1960s have increased levels of poverty instead of alleviating it! Peculiarly, as the welfare state replaces the earning father and the stigma of illegitimacy shrinks away, children in a traditional two-parent family are steadily declining (above 45%), especially amongst blacks in the USA.

Wars of economic conquest are invariably the result of some variant of mercantilism, socialism, or autarky (self-sufficiency of production), three economic theories that put the interests of the state in controlling the military first. Capitalism, which encourages international free trade, is almost never the reason for war. Socialists propagated a huge myth against a free-market society. The environment has taken a bigger hit under socialism across the world in the quest to use resources without any individual liability, says DiLorenzo.

Bashing the Right

The liberals and the ‘left’ bash with equal force the ‘right’ (conservatives or the Republicans) as domination by an elite incompatible with democracy, prosperity, and civilization. According to them, conservatism promotes inequality and prejudice. Preserving institutions that have apparently stood the test of time and a gradual organic change; believing in the hierarchy of orders and classes; and defining freedom in a concocted manner by internalising domination are the hallmarks of conservatism, say the critics. Liberals feel that conservatism works by destroying conscience, rejecting democracy, and opposing rational thought. Previously, it was by denying education, and in the modern era, it is by the invention of public relations—a rationalised irrationality. Conservatives destroy reason by using the trick of “projection,” attacking someone by falsely claiming that they are attacking you.

In the modern industrialised era, kings have given way to corporations and the prosperous middle class to subjugate the common masses in the new avatar of conservatism. The conservatism of the late 20th century was especially vituperative in its campaigns against the relatively autonomous democratic cultures of the professions, says one author, Philip Agre. Thus, a new subfield of public relations, issues management, and the invention of think tanks have subverted democracy, the critics of conservatism say.

Fascism: Right or Left?

Media, the film industry, intellectuals, and academic institutions play an important role in reinforcing the discourse of associating fascism with the ‘right-wing’ agenda. World over, the so-called right and its cousins like “Conservatives” or “Republicans” are always on the defensive in trying to prove that their actions are not fascistic, as the overwhelming diatribe comes from the other side. However, fascism might in fact be a manifestation of extreme leftist socialistic ideology.

Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, and Japanese imperialism, examples of gross fascism, were all national or international socialists. Fascism began with socialistic ideologies, complete governmental control of all institutions, and a hatred for private enterprise. The dogmas of German fascism were the abolition of private property, the sacrifice of individual freedom, the show of unity by indulging in violence against any defined enemy, the regulation of private business, and centralised governance. Education as a free commodity for indoctrination, intolerance to opposition, and being at continual war with individuals, families, private businesses, and the church to bring about a great reordering of society are common themes for both socialism and fascism.

Stalinist propaganda repeatedly claimed that the only alternative to Russian socialism was fascism, and thus the latter became the extreme right. Fascism now abusively refers to any government or individual in power trying to impose its views on non-consenting citizens. The fascists were strictly anti-Church, and the same philosophy of ranting by the socialists continues with respect to religion.

Jonah Goldberg argues that contemporary conservatism has neither roots in nor an affinity for fascism. Contemporary liberalism ironically retains an affinity for fascistic ideas through its profound indebtedness to progressivism. Group loyalty was the highest principle in Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, which were socialistic in character. Goldberg claims that liberals, leftists, progressives, and Democrats have always created moral equivalents of war to create an equal brand of fascism. In matters of economics, politics, sex, gay rights, abortions, environmental protection, citizen rights, and race inequalities, the liberals always appeal for unity and come together in the form of a ‘revolution.’

A prime example of the liberal left’s similarity to fascism is in the field of eugenics, a shameful chapter in the history of humanity in the early 20th century. Hitler was obsessed with the creation of the perfect race. Later, the prime drivers of eugenics were the liberal democratic “anti-fascist” presidents of the US, like Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt. The philosophy of science and technology as a prime mover in the scheme of things, the ends justifying the means, and attitudes against religion have a striking similarity between fascistic and liberal left-wing ideology, argues Goldberg.

In abortion too, the left-liberal support of pro-choice resonates more with the fascistic ideology of sacrificing the individual for the collective good. ‘Green fascism’ (carbon footprints, global warming, humans as a source of all problems, redemption of collective guilt by individual efforts, the individual for the whole) creates environmental scares today like the Nazis were previously obsessed with air pollution, nature reserves, and sustainable forestry. Is fascism extreme right or extreme left?

Do All These Make Sense?

As we shall see later, these right-left political ideas do not make sense either in the Western context or in the Indian context, and yet, for decades, we have held on to them. We need to understand our past political systems better, and we need to transcend the right-left paradigm. The simplistic models for political spectrums have created confusion, hostility, and dogmatism rather than illumination, writes Hyrum Lewis (The Myth of Left and Right and It’s Time to Retire the Political Spectrum). The author completely debunks the idea that there is some kind of essence in the terms ‘right’ and ‘left’. They have simply been ‘tribal’ solidarities joined by some common issue or cause. The later issues to support or oppose simply are a matter of conforming to the group solidarity. The political ideas of both the left and right have flipped in reverse directions across time in the USA and it is remarkable that without any essentialist definition, entire populations have been in the trap of a genuinely false narrative.

Adolf Hitler and libertarian Milton Friedman are on the ‘far right,’ yet Hitler advocated nationalism, socialism, militarism, authoritarianism, and anti-Semitism; Friedman advocated internationalism, capitalism, pacifism, civil liberties, and was himself a Jew. In short, the political spectrum teaches absurdly that opposites are the same. The two ‘positions’ are the mixing of incoherent, unrelated, and constantly shifting ideas lumped together by the accident of history. Aggressive military positioning hardly connects to a free-market philosophy. Defenders acknowledge this variation but claim an underlying essence: the right (conservatives), ‘backward looking’, want to conserve; the left (progressives), ‘forward looking,’ want change. Both wings’ policies, in fact, are ‘backward-looking’ and marked by nostalgia, depending on the issue.

That conservatives love the rich and love the country and liberals love the poor and hate the country would be another concocted and simplistic story. One can falsify every proposed essence of right or left, which shows us that ideologies are nothing but social constructs, argues Lewis. The test of truth is not storytelling but prediction; those clinging to the political spectrum make no predictions. The spectrum also leads to hostility. The intense attachment to one’s brand makes way for bigotry and hatred of the ‘other’. History, the guilt of the past, and the weak points of the present are the major weapons to use against the person on the other side. Fascism, totalitarianism, and absolutism can qualify for any ideology from the opposing camp.

In the next section, we shall see how these Western notions hardly fit India and shall trace the trajectory of post-independent India and its major political issues as assessed by eminent scholar Professor Dr. Bhikhu Parekh, a Padma Bhushan awardee.

Continued in part 2

SELECTED REFERENCES AND FURTHER READINGS:

- https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/6142/1/BLR%20conf%2C%20Bhikhu%20Parekh%20article.pdf The Poverty of Indian Political Theory by Bhikhu Parekh

- https://incarnateword.in/sabcl/15 The Incarnate Word, Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Volume 15

- https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/02/government-responsibility-to-citizens-anne-marie-slaughter/ 3 responsibilities every government has towards its citizens by Anne-Marie Slaughter

- The Story of Philosophy by Will Durant

- Political Ideologies: An Introduction (2022) by Andrew Heywood

- The Indian Conservative: A History of Right-Wing Indian Thought by Jaithirth Rao

- Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left by Roger Scruton

- The Problem with Socialism by Thomas DiLorenzo

- The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression by Andrzej Paczkowski, Jean-Louis Margolin and others

- https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/agre/conservatism.html What Is Conservatism and What Is Wrong with It? By Philip E. Agre (2004)

- Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, From Mussolini to the Politics of Change by Jonah Goldberg

- The Myth of Left and Right: How the political Spectrum Misleads and Harms America (2023) by Hyrum Lewis and Verlan Lewis

- https://quillette.com/2017/05/03/time-retire-political-spectrum/ It’s Time to Retire the Political Spectrum

PART 2

The Political Trajectory Of Post-Independent India

In the first part, we saw the general classification of Western political systems. Since the Greeks, Western thinkers have struggled to propose the best form of government. The utopian idea has always been that of maximally autonomous individuals under the protection of a neutral state. This part is primarily a summary of the essays of an eminent scholar and economist based in the UK, Dr. Bhikhu Parekh, who assesses post-independent Nehruvian India.

Introduction

The ‘right’ and ‘left’ now firmly entrench themselves in our minds despite glaring inconsistencies, as most continue to use them both informally and formally. Intellectuals have persistently questioned the relevance of Western political ideas to the lived experience in India or other non-western cultures. The most relevant in contemporary times is that of Dr. SN Balagangadhara and his group, who show that much of today’s normative ‘liberal democracy’ has clear theological roots and may not make sense outside the Western world. Universalising and secularising a theological theme may be problematic when applied to Indian culture. Independent India, ignoring indigenous political philosophy, inherited Western values, creating a story of contradictions clashing with the intensely traditional society of India.

Political theory offers society self-consciousness and self-understanding. It ensures rational debate on public issues and contributes to the creation of a civilised and healthy society. Non-Western societies have rightly complained that ethnocentric Western political theory, especially the gold-standard ‘liberal democracy’, has limited explanatory power outside the West. However, no contemporary non-Western society has produced much original political theory. The reasons have been different in different societies.

The following three sections are a summary and paraphrasing of the two important essays of Professor Bhikhu Parekh (Nehru and the National Philosophy of India and The Poverty of Indian Political Theory), where he assesses post-Independent Nehruvian India. Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister from 1947 to 1964, was a patriot, undoubtedly, but he constantly looked at the West as a template for India’s future, rejecting the indigenous past.

The Political Thought of Nehruvian Independent India

Nehru threw his weight behind the seven principles of a ‘New India’ (to bring it out of stagnation) based on modernity: national unity, parliamentary democracy, industrialization, socialism, scientific temper, secularism, and non-alignment. This ‘unofficial but official’ philosophy of India gained such supreme moral authority that few political theorists took the trouble of critiquing it.

National unity, the best protection against hostile forces, was Nehru’s top requirement for national independence. He believed that a strong, constitutionally bound, centrally governed government would address many issues, including narrow regional and caste loyalties, the forging of patriotism, and preventing fragmentation. He stressed industrialization and higher education for forging unity, ignoring primary education and cultural heritage as enduring bases for national unity. The ignoring of primary education led to a huge variety of schools with little coordination, no coherent framework of objectives, limited relevance to Indian conditions, and poor attempts to ground pupils in Indian history and culture. The future citizens of India grew up with little in common, sometimes sharing the minimum of memories and values with their parents. In some English-medium schools, the products were a confused mix of the West and India.

Parliamentary democracy with universal adult suffrage, fair elections, separation of powers, an independent judiciary, a free press, civil liberties, and constitutionally guaranteed basic rights was the only way to hold together a diverse, vast, and divided country. Alternatives like ‘communitarian’ and ‘organic’ democracy advocated by thinkers like Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo did not appeal to Nehru. Though Nehru owed his position to Gandhi, ironically, he was unsympathetic to the Gandhian idea of a loosely structured polity and preferred a federal polity with a strong centre.

Industrialization, a major route to political and economic independence, was the solution to India’s poverty and national weakness against foreign conquests. Nehru saw cottage and small-scale industries only as a temporary expedient until the country became fully industrialised. Nehru, in his inexorable industrialization, ignored agriculture as a lever of economic development. Nehru confirmed contemporary European thinking by placing agriculture as a primitive and culturally inferior activity. For Gandhi, villages held the key; for Nehru, villages were the problem.

Socialism was a lifelong commitment for Nehru. However, his social analysis throughout remained diverse and confused because Indian experiences did not match the theories. He tempered his pre-independence hard socialism (which threatened to isolate him) with a democratic form of socialism. The Second Five-Year Plan developed by Mahalanobis to create a ‘socialist society’ was the overall strategy for the Nehru period. It was a private-public sector mix with a dominant public sector. Nehru’s socialism had economic and political consequences. The concern was to increase production rather than provide a national minimum for all Indians. The five-year plans gave low priority to public action aimed at endemic undernourishment, illiteracy, basic medical facilities, clear drinking water, and cheap food. Public investment in education, health, housing, and goods distribution was not merely a matter of justice but also a vital socio-economic investment capable of yielding high long-term dividends. In that sense, his conception of socialism was structurally flawed.

Scientific Temper, his fifth national goal, desired the dogmatic, mystical, speculative, uncritical, inward-looking India to become a strong society like Europe through scientific reasoning. This meant the development of science and technology, fostering rational and empirical ways of thinking, and rejecting faith. He held the Orientalist view strongly that science and technology were primitive in ancient India, which was one of the reasons for its colonisation.

Secularism, the notion of state neutrality, and the separation of the public social sphere from the private religious sphere were straight imports of European ideas battling their religious issues. The debate on the relation between the state and religion ranged widely: the incoherent notions of “Hindu raj,” suppressing religion altogether; equal respect for all religions; or indifference to religion. Nehruvian secularism was an ambiguous and complex concoction of the last option. He was intensely hostile to the ideological and institutional dimensions of religion but deeply sympathetic to the spiritual dimension, though he never clearly defined the term ‘spiritual’.

Nehru’s state claimed all the rights of a ‘Hindu state’ in its relations with the Hindus. He took liberties with the Hindus, like objecting to the President inaugurating the rejuvenated Somnath temple; objecting to Bande Mataram because of religious connotations; allowing the Hindu Code Bill, which included state temple management; and insisting on debating religious issues as the Hindu personal law and banning cow slaughter in secular terms. But he dared not touch the Muslim personal law, despite his anxiety to have a uniform civil code. In claiming the rights of a Hindu state, Nehru’s government’s refusal to accept the obligations of defending and promoting their religion incurred charges of inconsistency and disingenuity in applying secularism.

Non-alignment was a key point of his almost single-handedly formulated foreign policy. In some areas, such as India’s relations with the scattered mass of overseas Indians and the countries of their settlement, Nehru never managed to develop a clear policy. In his foreign affairs policy, he did accept the civilizational importance of India. Gandhi, non-violence, and Advaita appealed as solutions to a world tired of violence and conflicts. He believed in “enlightened capitalism” co-existing with liberalised communism as the way forward to harmonise relations between the polarised worlds of capitalism and communism.

This non-alignment principle aimed for a world of new and proud states to attain the four crucial goals of national integration, economic development, self-determination, and freedom from external interference. Nehru’s foreign policy was, however, not adequately neutral. It freely expressed its views, took sides, and found itself allied with different groups on different occasions. Nehru’s international role had mixed consequences. It strengthened India’s self-confidence and self-esteem, brought India into various international commissions and organisations, and built useful contacts. But it also developed an exaggerated sense of its importance and mistook visibility for power.

Convinced of international support, India tended to take a somewhat patronising attitude towards its neighbours. In his concern for the world stage, Nehru did not give India’s neighbours the degree of attention and priority they deserved. He made the double mistake of neither coming to an understanding with them nor guarding against their aggressive designs.

Justification of National Philosophy

Nehru argued for this national philosophy as the only basis for constructing the new polity. Nehru invoked Indian civilization and culture but gave vague references to the ‘central lessons’ of Indian history and Indian character. For Hindus, secularism as a notion is completely alien, as traditions, a total way of life, regulate both personal and political life. Even other national goals such as parliamentary democracy, socialism, industrialization, and non-alignment had no or only a limited basis in Indian civilization. Except on issues such as a strong Constitution, many in Congress did not agree with Nehru’s goals.

Modernising as the best solution for our problems was driven by the conviction of Western superiority in the march of progress. According to the Orientalist narrative, ancient and mediaeval India were all about ignorance, superstition, scarcity, economic and social injustices, and tyrannical customs. His arguments were popular but open to objections when arguing that modern civilizations were morally superior. Civilizations, as self-contained wholes, are not amenable to comparative evaluation. Modernity’s constituents, such as rationalism, individualism, liberal democracy, the state, technology, a scientific worldview, utilitarianism, and economism, were not all logically related. They had come together in Europe because of historical factors and had different combinations in different societies, and some of them could even go. India could have developed its own distinct model of modernization.

India’s secularism has been one of the most glaring examples of transposing an idea from the West to an inappropriate soil. The same was true of the other ‘national goals’. India could have opted for other forms of democracy than the Westminster model. It could have opted for a more decentralised and participatory planning style, different from both capitalistic and communistic forms. In short, one could accept Nehru’s national ideology and yet arrive at either a different vision of the country or a different way of realising it. Nehru failed to make a convincing case for his national ideology, partly because he was not a rigorous thinker and, more importantly, because there can never be a rational demonstration of political ideologies.

Nehru’s national ideology, acquiring political dominance, primarily reflected the political consciousness of the Westernised elite, to whom it assigned a crucial role. Different parts attracted different classes. National unity, a strong state, and non-alignment appealed to most Indians; industrialization and parliamentary democracy to the elite; socialism (guaranteeing high prices for agricultural products and a supply of agricultural materials at stable prices) to the peasantry; and secularism to the minorities. The least benefiting, who remained its critics were the urban and rural poor, the unemployed, and the proponents of a Hindu country.

Broad enough to offer something to everybody; concrete enough to provide a sense of direction; ambiguous enough not to alarm or alienate a large section; and visionary enough to inspire and motivate millions, his national philosophy enjoyed widespread popular support. Nehru threw all his enormous personal and political authority into it, regarding it as an unquestioned premise of the Indian state. Winning three elections based on his national philosophy reinforced its moral and political legitimacy. Gradually, this became a national mantra. Nehru is indeed the founder of the modern Indian state. No criticism can take his love for India away from him. But, given the background of his education and training, his vision of India looked mainly West. Despite disagreements, critics have yet to develop an equally broad vision.

Major Political Debates of Post-Independent India

Indian political experience throws up questions on how Western ideas filter through their indigenous analogues; the different ways of political discourse in English and in the regional languages; the distinction between private and public in a society that refuses to separate the two; and the concept of the political in a society that has long seen it as an inseparable dimension of the social. There are also implications when a society, never structured around a state and not considering political authority autonomous, decides to reorganise along state lines. Some major political debates in post-independent India have been on reservations, the nature of the Indian state, federalism, and secularism.

Reservations

India, the only country with an extensive constitutional programme of positive discrimination (seats reserved in assemblies, public jobs, and professional academic institutes) in favour of deprived groups, wanted to integrate deprived groups into mainstream political life and address centuries of neglect and oppression. As a permanent government policy now, positive discrimination raises important questions about the nature of justice, the trade-off between justice and such other equally desirable values as efficiency, social harmony, and collective welfare, and the propriety of making social groups bearers of rights and obligations.

It also raises questions about the redistributive role of the state, the nature and extent of the present generation’s responsibility for the misdeeds of its predecessors, and the meaning of social oppression. Justice is generally an individualist concept; it is due to an individual based on his qualifications and efforts. Justice needs redefinition, obviously in non-individualist terms, if social groups are subjects of rights and obligations. We should also demonstrate continuity between the past and present oppressors and oppressed. We must also analyse the nature of current deprivation and determine that it is a product of past oppression, conferring moral claims on the oppressed. These questions are important in India, where positive discrimination has no roots in the indigenous cultural tradition and is much resented. There are few studies either challenging or articulating the theory of justice on the basis of reservations. Some work, however, relies on American literature without appreciating that the historical relations between upper caste Hindus and the untouchables and tribals bear little resemblance to those between American whites and blacks.

Nature of the Indian State

The modern state in India introduced by the British underwent important changes in response to its colonial requirements and the Indian social structure. Unlike Europe, it permitted a plurality of legal systems to share sovereignty with self-governing communities. After independence, India remained a complex political formation without correction. It has uniform criminal but not civil laws. Muslims, tribals, Christians, and Parsis have their own total or partial personal laws, which the state enforces but does not interfere with. The Indian state thus recognises both individuals and communities as bearers of rights. Criminal law recognises only individuals, whereas civil law recognises most minority communities as distinct legal subjects; thus, it is a liberal democracy of a very peculiar kind.

Federalism

India’s federalism has a distinct character. It is possible that in a multi-communal society, the modern state, committed to uniform laws, individualism, abstract equality, and undivided legal sovereignty, might alienate minorities to provoke conflicts and secessionism. By rejecting the idea that there is only one way to form the state and thinking about alternatives, we may be able to better deal with the ethnic conflicts and secessionist movements that the dominant model of the state is now confronting. Maybe the state should not separate from society in the first instance. Rather than insisting on a uniform legal system, we might allow its constituent communities to retain their different laws and practises within the ambit of widely accepted principles of justice. Hardly any Indian political theorist has challenged the basic categories of Western political thought and theorised the specificity of the Indian state.

Secularism

Our founding fathers, concluding for a secular India, remained muddled on the meaning of secularism. Selective interference in Hindu matters, non-interference in Muslim personal laws, and giving public money to Muslim schools were peculiar secularistic policies. The Congress wanted to deny the dominant and distinct Hindu ethos from the beginning. Secularism changed from an equal indifference to an equal respect for all religions during Indira Gandhi’s tenure, becoming equally vague and incoherent. No government has fully explained why India should be a secular state in its current sense; the arguments are unimaginative and derived from Western history.

Most leaders have argued falsely for secularism as necessary for religious tolerance and harmony. A secular state is not necessarily tolerant (like the Soviet Union during Communist rule or France after the French Revolution), and a religious state is not necessarily discriminatory against minority religions (like traditional Hindu kingdoms in India, Muslim kingdoms in the Middle East, and most of the time even in India). Secularism, with no Indian vernacular equivalents, does not even make sense in the Indian context, where the majority ‘religion’ is unorganised and doctrinally eclectic. Since Indian civilization has a deep religious core, many secular Indians have felt that they cannot be truly secular unless they reject their past completely and choose the future. Hardly anyone has cared to show that the dilemma is unnecessary and arises from a falsely defined model of secularism.

Poorly theorised political questions in India

Surprisingly, post-independent India failed to define traditional ideas on subjects like social justice, the specificity of the Indian state, secularism, legitimacy, political obligation, citizenship in a multi-cultural state, the nature of the law, the ideal polity, and the best way to theorise the Indian political reality. Gandhism, conservatism, liberalism, and socialism were the four major pre-independence political traditions.

Post-independence, Gandhism made a retreat; conservatism did not achieve prominence despite original work by Bipin Chandra Pal, Sri Aurobindo, Swami Vivekananda, and Tilak. Liberalism had selective interpretations in writers like Ram Mohan Roy, Dadabhai Naoroji, and Gokhale. Communist Party theoreticians never offered an original interpretation of Marx in light of Indian history and experiences.

Work continues on Kautilya’s Arthashastra, but apart from that, there are no major reconstructions of ancient or mediaeval Hindu, Jain, or Buddhist texts on politics that discuss how Indian thought differs. Most Indian political theorists broadly engage in two categories: bulk repetitive work on the structure of nationalist thought; and derivative work on contemporary Western writers or movements (positivism, behaviourism, and so on). Critical relativism, an evolving category, holds the promise of affirming the autonomy and integrity of Indian forms of thought and life. Contemporary political theorists have taken little interest in producing creative theories for three reasons:

- The way Indian universities teach political theory: (best students staying away from social sciences; mediocre teachers; poor English command making creative thinking in a non-vernacular language difficult; an inadequate curriculum at the UG or PG level rarely focusing on Indian thought; and many good ones falling to the temptation of toeing the Western line and becoming Indian critics)

- The domination of the ‘unofficially official’ Nehruvian political philosophy meant that if someone is against secularism, it must be for ‘Hindu raj’; if against socialism, it must be for unbridled capitalism; if against scientific temper, then for religious obscurantism; and so on.

- The political theorist’s ambiguous attitude towards the complex Indian political reality: The success of the linguistic states’ reorganisation or local self-government (Panchayati Raj), considered subversive and reactionary, surprised political theorists and leaders. India is moving from a loosely structured rural society to a path of industrialization. Political theory, taking the state as its starting point and understanding society in relation to it, replaced traditional social theory, which concentrated on the social structure with the government as one of its many institutions. Traditional Indian political theory grounds itself in a moral consensus about the nature of the social structure and its members’ duties rather than rights. A radical transformation to cope with the vastly different social reality and theorization of New India could not thus happen in the traditional manner.

Indian political theorists have poor knowledge of Sanskrit but a good grounding in Western political theories. The Indian political theorist needed to go West and come back. Some never left home; some went and stayed in the West both physically and theoretically; a few did return but continued to think West. Western writers discuss change against the background of stability and order, whereas the Indian political theorist, as a human being living in a society in flux, carries all its ambiguities in his thought.

The modernist does not believe that his tradition is beyond salvation, and the traditionalist finds it difficult to sustain his faith in light of India’s steady decline for several centuries. The modernist wants a casteless society but has lived his or her life in the secure confines of caste and uses caste resources in times of need. Conversely, the traditionalist likes and uses many of the resources of the modern world. Not surprisingly, many political theorists find it difficult to develop realistic perspectives on their country’s predicament.

Colonial rupture in Indian thought; the cognitive alienation of intellectuals from their society; the difficulty of theorising in English a reality constituted in vernaculars; and practically oriented Indian traditions; have been other factors responsible for poor political theorising too. Political theory requires many things: bold and challenging minds; a love of theoretical understanding; intellectual self-confidence; a climate of tolerance; a relatively firm political reality; the theorist’s ability to get a critical grip on it; and the theorist’s stable moral and emotional relationship to the environment. The absence of all or most of these conditions explains why political theory has not developed in many Third World countries but only in some Western countries during certain historical periods.

Cultural Superimpositions: The Example of Indian Law

The Indian judicial system today is arbitrary and opaque, with the judges holding an inordinate amount of power. Balagangadhara (Cultures Differ Differently) shows how superimposing Western law on indigenous cultures with their own ways of law and justice leads to the severe distortions that we face today.

Some scholars credit the great British law as a ‘gift’ to Indians wallowing in decadence and lawlessness. However, British society and law were corrupt to the core in the 18th and 19th centuries, when they were ruling a great part of the globe. Their neighbours, allies, and cultural relatives saw them as corrupt, contemptible, hypocritical, and immoral. The British in India did whatever pleased them, but the judges and bureaucrats clothed these acts in a legal language and many non-existent laws. Ironically, there was hardly equal justice in British India. Local European communities did not allow Indian judges and law officers to try them, and they got away with the most brutal crimes through lenient European judges.

Balagangadhara then explains how Indians, after independence, as cultural beings, believing the British law and institutions to be the ideal, mixed them with their own ideas relating to justice, truth, persons, and so on. He gives the example of the notions of ‘truth’ and ‘falsity’. These notions have roots in Christian theology. In Indian culture, there is a clear semantic distinction between lies and deception. The socialisation process in Indian culture even involves learning to lie. Deception, however, is clearly separate from lying. Thus, lying under oath loses its reasoning in law (ratio legis). Yet ‘perjury’ remains a punishable offence in the Indian legal system.

In Western culture, it is the fair, objective, and impartial law that judges, not the person of the judge. In contrast, the Indian judge has a self-view as the ‘embodiment’ of justice, dispensing ‘justice’, often completely independent of, or even oblivious to, legal provisions and statutes. Even for many people going to court, the judge represents justice embodied and personified. This attitude helps us understand the massive corruption of the judiciary in India.

The law in Western culture tries to reduce arbitrariness and capriciousness in settling disputes. But the imposition of Western institutions in India encourages precisely the arbitrariness that the law is supposed to prevent. The figure of the ‘judge’ now uses the legal institution, which gives him the power to do what he does, to make arbitrary pronouncements because of the culturally specific notion of the judge. In indigenous cultural institutions, reasonableness prevails because the judge faces the community directly and owes an explanation to the community in which he lives. In modern courts, such constraints on reasonableness are absent.

Politics and law in Western culture are meant to further the general interests of society but not those of any single community, group, or individual, especially corporate interests. Strikingly, Balagangadhara says, Indian culture does not have a vocabulary to understand any kind of discourse on interests, whether institutional, private, public, general, or social. If such is the case, legislation is meant to explicitly favour specific groups, which would give them votes. The Parliament’s reasons for implementing the laws are not in the general interests of society but are as narrow as the reasoning of an individual who contemplates his own benefit. The British made laws that favoured British interests but cloaked them in the language of ‘general interest’ and ‘interest of the Empire’. ‘Protecting the British interests’ later took the form of the ‘protection of minority interests’ in the Indian Constitution.

When the state promulgates laws that only favour and further narrow interests, citizens end up using such laws mostly retributively. Seeking personal vengeance (dowry, atrocity, and so on) becomes the major, if not sole, goal of the citizenry when they go to the courts. Thus, when implemented in India, the institutions of Western law encourage just the opposite of what such laws are meant to do: a vengeful, spiteful, and ‘selfish’ citizenry. Instead of promoting a cohesive society, such laws encourage divisiveness and conflict in society.

In the next section, we shall briefly look at the amazing political text, Kautilya’s Arthashastra, along with the political thoughts of prominent modern Indian thinkers. Sri Aurobindo, Ananda Coomaraswamy, and SN Balagangadhara are some who have been extremely uncomfortable with Western political models. As all of them stress, the superimposition of Western thoughts on indigenous systems has generally led to a chaotic situation, and we need a lot of will and effort to correct this.

Continued in Part 3

SELECTED REFERENCES AND FURTHER READINGS

- https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/6142/1/BLR%20conf%2C%20Bhikhu%20Parekh%20article.pdf The Poverty of Indian Political Theory by Bhikhu Parekh

- https://www.epw.in/journal/1991/1-2/special-articles/nehru-and-national-philosophy-india.html Nehru and The Political Philosophy of India

- Law, religion and culture by S.N. Balagangadhara in Cultures Differ Differently: Selected Essays of S.N. Balagangadhara. Edited by Jakob De Roover and Sarika Rao

PART 3

“The stronger and more intense the social is, the less it is oppressive and external” (G. Gurvitch). “In a medieval feudalism and imperialism, or any other civilization of the traditional type, unity and hierarchy can co-exist with a maximum of individual independence, liberty, affirmation, and constitution” (Evola, Rivolta). But: “Hereditary service is quite incompatible with the industrialism of today, and that is why the system of caste is always painted in such dark colors” (A. M. Hocart, Les Castes, Paris, 1938, p. 238).

–Ananda Coomaraswamy in “Primitive mentality”

Indigenous Political Thinking In Ancient And Modern India

In the previous parts (1 and 2), we saw the overall understanding of political systems in the Western world and the political trajectory of post-independent India, primarily determined by Jawaharlal Nehru, who was the Prime Minister of the country uninterruptedly from 1947 until his death in 1964.

In this part, we shall look at the most famous ancient political text in India, which had some great insights into political organisation. Dharma was the basis of all Indian activity in any field, and there was never a proper understanding of this despite repeated stress by some prominent modern thinkers like Sri Aurobindo and Ananda Coomaraswamy. In contemporary times, SN Balagangadhara and the Ghent School are giving some important insights into the nature of traditional Indian political discourses.

Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Others

Kautilya’s Arthashastra (2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE), influential till the 12th century CE, was a solid political treatise (six thousand shlokas, one hundred and fifty chapters, and fifteen books) covering almost all aspects of ruling a kingdom. The text makes explicit the four sciences in society from which everything concerning righteousness and wealth derives: Anvikshaki (the philosophies of Sankhya, Yoga, and materialism); Trayi (the triple Vedas); Varta (agriculture, cattle breeding, and trade); and Danda-Niti (the science of government).

Philosophy, or Anvikshaki, gives light to all kinds of knowledge; the Vedas teach about righteous and unrighteous acts (Dharmadharmau); and the Varta about wealth and non-wealth. These, in turn, depend for their well-being on the science of government, which alone can procure the safety and security of life. It says that the sciences should be under the authority of specialist teachers, while theoretical and practical politicians should teach Danda-Niti.

Arthashastra details the obligations of each of the four varnas and the four ashramas—Brahmacharya (student), Grihastha (householder), Vanaprastha (retired), and Sannyasa (renunciate)—of a domestic-spiritual life, a basis for a well-ordered and harmonious society. The overarching framework for these varnas and ashramas are the four purusharthas (purposes): dharma (morality), artha (wealth), kama (desires), and moksha (enlightenment). Harmlessness, truthfulness, purity, freedom from spite, abstinence from cruelty, and forgiveness are duties common to all.

The king should never allow people to swerve from their duties. The ideal prince learns military arts, Itihasa, Purana, Itivritta (history), Akhyayika (tales), Udaharana (illustrative stories), Dharmasastra, and Arthasastra from disciplined teachers. The well-educated king, devoted to the good governance of his subjects and bent on doing good to all people, will enjoy the earth unopposed, declares the treatise. Arthashastra is a prototypical example of the textual material of India, laying out the ideal and practical aspects of administration and the behaviour of kings, citizens, and governments to the finest detail. The organisation of the government departments, the method of revenue collection, the restrictions on illegal trade, the method of choosing the kings and key administrative officers, the rules of agriculture, the encouragement of artisans, and so on are in such excruciating detail that one could as well develop the treatise for contemporary times.

Among the many texts like the Ramayana, Mahabharata (especially the Shanti Parva), and Tirukkural, the focus has been on duties rather than rights for both the rulers and the ruled. Dharma, though difficult to translate, definitely not implying religion, is, in its broadest possible scope, the maintenance of cosmic order. Each sentient being has a duty, according to his station in life, to maintain that order. Hence, the interpretation of dharma in the Indian context has always been about duties rather than rights, a situation opposite to the Western ideas of individualism and rights. The consistent theme of our scriptures and texts is to describe and ensure an enlightened monarchy. Our political philosophy has been radically different from the rights-based approach of most liberal democracies.

Interestingly, ancient India (Saptanga tattva in Manusamhita or Sapta–prakriti in Kautilaya’s Arthashastra) conceptualised the nation-state as comprising seven-fold organs: Swami, or King or sovereign ruler; Amatya (Ministers); Janapada (country or region or province and its residents); Durga (secured fort or town or Capital); Kosh (treasury); Danda (punishment to the criminals); and Mitra (group of different faithful nations and kings). In Sukraniti, another Indian manuscript, there is a similar seven-fold ‘organic theory’ of the nation-state: King is the head; Minister is the eye; Mitra, or friend, is like the ear; Danda, or punishment process, is the power; Kosh is the mouth; Durga, or secured town or capital, is the hand; and Janapada is like the leg of the nation.

The overwhelming Indian model was thus an enlightened monarchy, decentralised units, and free citizens who could cross the borders without attracting charges of treason. The citizens of Bharat had a deep cultural and spiritual bond that gave them unity despite enormous diversities in customs and languages. Undoubtedly, there were wars and battles, but on some principles, like never attacking the common citizens or destroying temples or agricultural lands. Taking slaves from the defeated land was unknown.

Dharma in Indic Political Philosophy

Our foundational texts emphasise the four core human values: Dharma (right living), Artha, Kama, and Moksha. This diverges from the Western rights-based individualistic philosophy. The pursuits of Kama (passion or desires) and Artha (political or economic wellness) are always acceptable if they base themselves upon dharmic values of harmony of the individual with society. The goal always remains moksha, or enlightenment, in all human endeavours — the release from bondage to complete freedom.

As Jaithirth Rao (The Indian Conservative) explicates, Dharma has three important ideas: Charitra, Raja, and Sukshma. Charitra, the character of individuals and groups, focuses on peace, harmony, and mutual trust. Raja Dharma (appropriate royal conduct), predating Magna Carta by centuries in suggesting that the sovereign is not above the law, promotes the happiness of the subjects as a protecting and non-predatory state. Sukshma Dharma comes into play when conflicting actions appear equally virtuous. Yuga Dharma, an idea going back some 2500 years (Apastamba Sutra of the Yajur Veda), suggests that each time period requires different dharmic responses from the virtuous. Apad Dharma is dharma-modifying during times of stress and war. Our traditions thought of almost all situations and the dharma of such times.

The Atharva Veda and the Isavasya Upanishad want us as trustees responsible for our possessions — the inherited land, ideas, culture, arts, thoughts, and philosophies — to pass on in an intact or better state to our descendants. In the economic field, texts like Tirukkural and persistent Indian institutions (the mandi and the bazaar) favoured free markets, says Jaithirth Rao. In traditional Hindu kingdoms, the polity and the social order were inseparable.

The king’s dharma consisted of preserving and enforcing the varna and jati-based social structures. Neither the modern concept of democracy nor its parliamentary articulation have a parallel in Indian thought. Karma determined an individual’s birth and natural endowments and thus fully deserved them; the modern notion of ‘group justice’ has no analogy in much of Hindu thought. In the Hindu theory of Purusharthas, several constraints surrounding the acquisition of artha could not form the basis of modern industrial society, as Bankim Chatterjee skillfully showed in his Samya, says Jaithirth Rao.

The king’s belief systems could be independent of those of his citizens, an impossibility in Western monarchies. A citizen could cross kingdoms without charges of treason, and there was no concept of slavery as ‘a person ruling over another’ in Indian culture, says Dr. SN Balagangadhara. Though contemporary scholars might try to torture our texts and Vedas to find evidence of slavery, it was non-existent, as was true in the West, which has a deep and troubling history of slavery.

Indic political philosophy has been consistently conservative in nature. Organic evolution, rather than a radical revolution, was the basis of change. Sanatana (Eternal) Dharma is harmony, starting from the individual self to encompass wider areas of family, society, and the state. Dharma ultimately talks of balance and harmony with not only fellow humans but animals, non-living objects, and the environment around them. The principles of feminism, ecologism, humanity, and acceptance of diversity intricately permeate through our best philosophical traditions. Giving a separate voice to these issues makes us distinctly uncomfortable, as it presupposes that Indians never thought about them.

Modern Indian Thinkers: Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo was one of the most profound thinkers of modern India and wrote extensively on all matters concerning India. He was critical of the Westminster model of parliamentary party-based governments and said it was unsuitable for India. Like Tagore, Sri Aurobindo was uncomfortable with the European idea of the nation-state, which he thought was only a forced political unity that was fragile in nature. The risk of such nation-states and their consequent nationalism was obvious in the colonial expansions and the world wars. For Aurobindo, political unification was secondary to another deeper form of unity already existing in India.

Sri Aurobindo understood a nation as a true unity instead of an empire, which is a political unity. Political unity is utterly destructible. A nation, on the lines defined by Sri Aurobindo, on the contrary, is considered to be the “living group-unit of humanity,” from which we can emerge into internationalism too. In The Ideal of Human Unity (The Ancient Cycle of Prenational Empire-Building), Sri Aurobindo details the development of nations in cycles. In the first cycle, a local unit overshoots the regional and national units to become an imperial body. There is a forcible unity among other local units. The second cycle has three successive intermediate stages: a) feudalism; b) the grip of absolute sovereign authority, namely the King; and c) finally, the Church. The third cycle tends to be representative of the ‘whole conscious,’ be it individual or community, which absorbs all. This has strong roots in the minds of its citizens.

Through decentralisation, the subordinate parts tend to merge into a stronger nation. Sri Aurobindo proposes the apex system of nation-building: nation (Rastra), state (Rajya), province (Pradesh), village (Gram). Like Gandhiji, he saw the village as central to nation-building. It was the basic unit of the nation, like the human cell is to the whole body. Gandhiji, however, placed villages as an independent unit with other units like districts, provinces, and the nation as larger circles surrounding the inner one. Sri Aurobindo’s model was an apex system where there was an independent yet dependent organic relationship between the primary unit and the higher organisations of complexity.

For Sri Aurobindo, spirituality of a high kind united India into a nation, and this spirituality was the basis of any Indian field like arts, literature, music, dance, drama, sciences, economics, social life, and politics. The spiritual message of India was the greatest message for the whole world suffering from strife and friction. For him, the Self (or the Brahman of Advaita) in all was the true basis for the unity of all individuals in the nation. India has had that message since ancient times. The spiritual message would be the basis for true internationalism too.

Consistently critical of politicians and political parties, he offered a decentralised polity with “one Rashtrapati at the top with considerable powers so as to secure continuity of policy, and an assembly representative of the nation. The provinces will combine into a federation united at the top, leaving ample scope for local bodies to make laws according to their local problems… Western polity conceives of doing away with political parties and creating governments of national unity only in times of war or crisis; India, because of her long tradition of a unity underlying her diversity, should have shown that unity is not a freak phenomenon but a workable basis for new politics.”

Following independence, India’s attempt at decolonization was less than half-hearted. As Michel Danino says, its apparatus remained wedded to a British constitution, a British polity, a British judiciary, a British administration, and a British educational system—a prison that is about the antithesis of what Sri Aurobindo envisioned.

Secularism would have made no sense to Aurobindo, who says, “Hinduism has left out no part of life as a thing secular and foreign to the religious and spiritual life… My idea of spirituality has nothing to do with ascetic withdrawal, contempt, or disgust for secular things. There is to me nothing secular; all human activity is for me a thing to be included in a complete spiritual life.”

Regarding caste, he says, “There is no doubt that the institution of caste degenerated. It ceased to be determined by spiritual qualifications, which, once essential, have now come to be subordinate and even immaterial, and is determined by the purely material tests of occupation and birth. By this change, it has set itself against the fundamental tendency of Hinduism, which is to insist on the spiritual and subordinate the material, and thus lost most of its meaning.”