First Published in Brhat Online Magazine as a Three Part Series

https://www.brhat.in/dhiti/indianknowledgesystems1

https://www.brhat.in/dhiti/indianknowledgesystems2

https://www.brhat.in/dhiti/indianknowledgesystems3

The purpose of this series of three essays is to make the reader aware of the richness of Indian knowledge systems. It also focuses on the ontological and epistemological foundations of Indian knowledge systems. The series tries to give an overview of how Indian metaphysics differs from the scientific and modern perspectives of knowledge production and understanding of reality.

The author does not make any claim of original scholarship in these areas. He is only trying to understand what the great scholars have already said. The essays draw heavily on the works of Śrī Chittaranjan Naik, Śrī Shatavadhani Ganesh, and Dr. SN Balagangadhara Rao. It is a paraphrasing and summarising of their works, and hence there may be direct quoting without indication in each case. Every effort has been made to attribute the work correctly.

PART 1- AN OVERVIEW

Introduction

We have a legitimate heritage to be truly proud of, without requiring outside validation. How did it happen that everything in Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) suffers from ignorance or denial? Everything good in India seems to be derived from the Greeks, Romans, Mesopotamians, Chinese, Arabs, or Europeans, and rarely from Bhārata itself! Simultaneously, critics have a field day at the extreme claims of head transplantation, flying aeroplanes, and cloning in the Indian past.

The linear progression of history from a “primitive” past to an “advanced” future, deeply entrenched in western philosophy, embeds itself in Indians even today as a classic case of ‘colonial consciousness’, explained by Dr. S. N. Balagangadhara. It is a misfortune of our education system that few have heard of Śrī Dharampal and his books like The Beautiful Tree and Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century. The colossal work of Śrī Dharampal in deconstructing the discourse – which leads us to conclude we were primitive before the colonials came – is vital to shaking off our persisting colonial consciousness.

Beginning in 1964 – 65, through over a decade later, Śrī Dharampal went into the deepest corners of archives and records in various libraries in India and England. He meticulously reconstructed from the archives what the British discovered and thought about Indian society. The archival material of the colonial descriptions of Indian sciences and technologies seriously undermines the legitimacy of standard perceptions about Indian society. Studied neglect, contempt, and the economic breakdown uprooted and eliminated indigenous sciences and technologies not only from society but from Indian memory itself, says Śrī Dharampal.

Contrary to the standard teaching, Indian society was functioning well and was extremely competent in the arts and sciences of its day, when the British started their rule. Its interactive grasp over its immediate natural environment was undisputed; in fact, it demanded praise. For example, Reuben Burrow says in 1790 that –

Hindoo religion probably spread over the whole earth; there are signs of it in every northern country and in almost every system of worship.

Burrow thought that Stonehenge, Arithmetic, Astronomy, Astrology, Holidays, Games, names of the stars and figures of the constellations, ancient monuments, laws, languages, and the Druids of Britain clearly descended from the ‘Hindoo world’!

English education is perhaps a major factor in generating and perpetuating this colonial consciousness. The statement that Ananda Coomaraswamy made more than a century ago makes sense even today:

A single generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and to create a nondescript and superficial being deprived of all roots—a sort of intellectual pariah who does not belong to the East or the West, the past or the future. The greatest danger for India is the loss of her spiritual integrity. Of all Indian problems, the educational is the most difficult and most tragic.THE BROAD CLASSIFICATION OF INDIAN TEXTS

Apart from the non-orthodox Buddhist and Jain corpus of texts, the orthodox Sanātanī texts divide broadly into the Śruti (that which is heard) and Smṛti (that which is remembered). The Vedas constitute an important part of Indian culture and civilization, but they are by no means the only one. Also, a belief or disbelief in the Vedas does not in any way reflect the status of being a Hindu or belonging to the Indian civilizational heritage.

Five groups of texts — Veda, Upaveda, Vedāṅga, Purāṇa, and Darśana — lay the foundation for the knowledge and wisdom of our heritage and cover the concrete and the abstract, the so-called ‘secular’ and the ‘spiritual.’ The separation of the sacred and the profane makes no sense in Indian traditions.

Thus, as Śrī Aurobindo and Ananda Coomaraswamy stressed, the concept of secularism ends up becoming an intense attack on Indian culture. It is a culture where all matter and all fields of activity (literature, arts, poetry, dance, drama, science, and technology) are intensely “spiritualized.”

Vedas

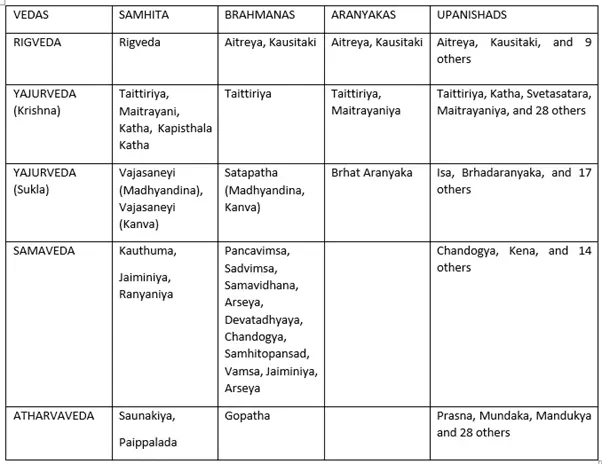

There are four Vedas, which are the core Śruti texts:

- Ṛgveda (ṛks or verses)

- Yajurveda (yajus or prose)

- Sāmaveda (sāmans or songs)

- Atharvaveda (Sage Atharvaṇa’s compositions)

Each Veda further subdivides into four sections:

- Saṃhitā

- Brāhmaṇa

- Āraṇyaka

- Upaniṣad

The Saṃhitās deal with bhakti (devotion); the Brāhmaṇas with karma (work, action, ritual); and the Āraṇyakas with dhyāna (meditation). These three dealing with rituals and devotional activities form the Karma-kāṇḍa.

The Upaniṣads (or Vedānta, the final portion of the Vedas) form the Jñāna-kāṇḍa — treatises on the philosophical aspects and deep discussions on the body, mind, soul, nature, consciousness, and the universe. Of the several Upaniṣads (at least 108 of them), ten are most important: Īśa, Kena, Kaṭha, Praśna, Muṇḍaka, Māṇḍūkya, Taittirīya, Aitareya, Chandogya, and Brhadāraṇyaka.

Loosely, the Vedic divisions also associate with the āśramas or stages of life: the Saṃhitās correspond to brahmacarya (student) āśrama; the Brāhmaṇas correspond to gṛhasta (householder) āśrama; the Āraṇyakas correspond to vānaprastha (forest dweller) āśrama; and the Upaniṣads correspond to saṃnyāsa (the ascetic) āśrama.

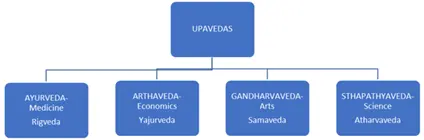

The Core Vedic Texts – (1) Upavedas

Upavedas (upa, or ‘secondary’ to Vedas) are bodies of aparā (material) knowledge, though still intimately linked to parā (transcendental) insights. Each Upaveda corresponds to one Veda. The Upavedas and Vedas also support the classical concept of Purusartha, the four objectives of life: dharma (duty), artha (material wealth), kāma (intellectual desires), and mokṣa (liberation, freedom).

The Upavedas concern themselves mainly with artha and kāma (‘pravṛtti’ or practice in the outer world), while the Vedas are about dharma andmokṣa (‘nivṛtti’ or practices for the inner world of Self-realization). However, these are not at all strict, as there is an expected overlap in the purposes of the huge corpus of literature.

They include the following:

- Āyurveda

- Arthaveda

- Sthāpatyaveda

- Gāndharvaveda

- Dhanurveda

Āyurveda is the medical and surgical science, and some foundational texts include Suśruta Saṃhitā, Caraka Saṃhitā, Aṣṭāṅga Hṛdaya, Vāgbhaṭa Saṅgraha, andBhāvaprakaśa.

Arthaveda is the wisdom of not only economics but also political science, law, ethics, constitutional studies, defense, management, sociology, trade and commerce, and civil and military engineering. Some of the renowned Arthaveda texts are: Artha-śāstra (Kauṭilya), Pañca-tantra, Yukti-kalpataru, Nīti-kalpataru, Nīti-sāra, Hitopadeśa, Nīti-sūtra, Nīti-vākyāmṛta, Vyavahāra-mayūkhaḥ, Rāja-nīti-mayūkhaḥ, and Rāja-nīti-ratnākāra.

Sthāpatyaveda forms the wisdom of engineering. Sthapati was a head engineer, under whom were sūtradhāras (design engineers), śilpis (sculptors), kārukas (artisans), takṣas (carpenters), kalādas (goldsmiths, silversmiths), kārmāras (blacksmiths), kulālas (potters), tantuvāyas (weavers), and so on. Sthāpatyaveda includes the basic sciences of physics, mathematics, and chemistry and their applied forms like mechanical engineering, civil engineering, chemical engineering, hydraulics, mechanics, and dynamics. The texts of the Sthāpatyaveda included Māna-sāra, Mayamatam, Viśvarūpam, Aparājitapṛccha, Samarāṅgaṇa-Sūtradhārā, and Rūpavastumaṇḍana.

Gāndharva-veda is the wisdom of arts and crafts. The Yajurveda mentions twenty-eight types of arts and crafts. The number of arts and crafts increased over time, and later literature mentions the famous sixty-four arts (catuḥ-ṣaṣṭi-kalā). This includes not just the fundamental arts like poetry, music, dance, theater, painting, and sculpture; but also secondary arts like flower arrangement, magic, juggling, carpentry, and so on. Some of the important texts are as follows: Kāma-sūtra, Nāṭya-śāstra, Kāvyālaṅkāra, Kāvya-darśaḥ, Dhvanya-loka, Śṛṅgāra-prakāśa, Sarasvatī-kaṇṭhābharaṇa, Vakrokti-jīvita, Vyakti-viveka, and Kāvya-prakāśa.

The famous Kāma-sūtra (Sage Vātsyāyana, period between 400 BCE and 200 CE) discusses love and lovemaking with an overall awareness towards a person’s life and society; and furthermore, includes discussions on sociology, aesthetics, ethics, medicine, anthropology, and psychology. The Nāṭya-śāstra (Sage Bharata, period between 200 BCE and 200 CE) is a comprehensive encyclopedia of all performing arts, as well as literature and architecture. It deals with the emotions, sentiments, and moods of theatrical communication. It also deals with methods of presentation; creativity; vocal and instrumental music; lyrics; grammar and figures of speech; stage construction, building sets, and architecture; costumes, jewelry, and make-up; and the education of the actors, dancers, and connoisseurs.

Some scholars include Dhanurveda, the science of archery, as one of the Upavedas. However, there are no foundational texts specifically under Dhanurveda.

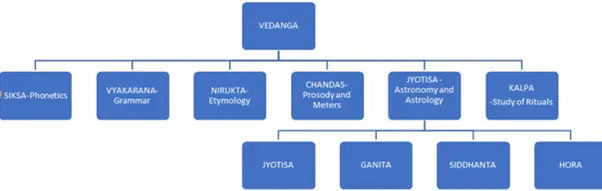

The Core Vedic Texts – (2) Vedāṅgas

Vedāṅgas are the limbs (aṅgas) of knowledge (veda). They are the six auxiliary disciplines essential to the study of the Vedas and include the following:

- Śikṣā (phonetics)

- Vyākaraṇa (grammar)

- Chandas (prosody)

- Nirukta (etymology)

- Jyotiṣa (astrology/astronomy)

- Kalpa (ritual)

Śikṣā (phonetics, phonology) is the study of the pronunciation of a language. Śikṣā reveals the sophistication of the Saṃskṛta language and of the Vedas. The texts on Śikṣā include Ṛgveda Pratiśākhya (Śākala Śākha), Śukla Yajurveda Pratiśākhya, Taittirīya Pratiśākhya, Atharvaveda Pratiṣākya (Śaunakīya Śākha), Śaunakīya-Caturādhyāyikā, Yājñavalkya-śikṣā, Nārada-śikṣā, Māṇḍūkī-śikṣā, Pāṇinīya-śikṣā, and Śikṣā-saṅgrahaḥ.*

Vyākaraṇa is the most important study of grammar. Saṃskṛta grammar, especially the system of Pāṇini, is known for its perfection, richness, depth, and beauty. Texts on grammar include: Aṣtādhyāyī (ṛṣi Pāṇini), Vārtikā (ṛṣi Vararuci), Mahā-bhāṣya (ṛṣi Patañjali), Vakyapadīya (ṛṣi Bhartṛhari), Mādhavīya-dhātu-vṛtti (ṛṣi Sāyaṇa), and Siddhānta-kaumudī (Bhaṭṭoji Dīkṣita).

Nirukta, the study of etymology, is auxiliary to the study of grammar. Grammar tries to develop a word, while etymology tries to analyze it. The texts are: Nighaṇṭu (Yāskācārya), Nirukta (Yaskācārya), Amarakośaḥ (Amarasimha), Trikāṅḍa-śeṣaḥ andVaijayantī-koṣaḥ (Yādava-prakāśa).

Chandas, the study of prosody and rich poetical meters in Saṃskṛtam, is extremely crucial to understanding the verbal utterances of hymns from the Veda. The texts include: Chandaḥ-śāstra (ācārya Piṅgala), Vṛtta-ratnākara (ācārya Kedārabhatta), Chandonuśāsana (ācārya Hemacandra), and Chandānuśāsana (Jayakṛti).

Jyotiṣa includes astronomy and astrology. The former is a factual description of celestial bodies and their behaviors. Astronomical observations, mathematics, and calendar making were the highly interlinked and deepest skills of ancient Indians. Astrology, a probabilistic system based on the above three, unfortunately got prominence in the narratives of a “superstitious” India.

There are four sub-groups in the Jyotiṣa group: Jyotiṣa (astronomical observations), Gaṇita (mathematics), Siddhānta, and Horā (astrology). The texts are Vedāṅga-jyotiṣa (ācārya Lagadha), Bṛhat-saṃhitā (ācārya Varāhamihira), Brhad-jātaka (ācārya Varāhamihira), Āryabhaṭīyam (ācārya Āryabhaṭṭa), Sūrya-siddhānta (ācārya Bhāskara), and Siddhānta-śiromaṇiḥ (ācārya Bhāskara).

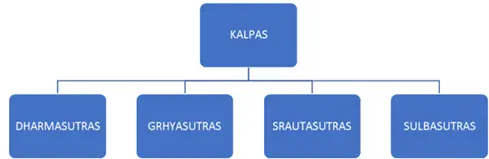

Kalpa, the study of rituals, covers a vast expanse of knowledge, including ethics, sociology, politics, traditions, and worship.

Sub-Groups Of Kalpas

Kalpa texts have again four main sub-groups of texts:

- Dharmasūtras (rituals, duties, and responsibilities at a societal level)

- Gṛhyasūtras (household rituals and duties)

- Śrautasūtras (rituals and worship of the Vedas)

- Śulbasūtras (construction of the altar for Vedic fire ritual).

The Dharmasūtras include Vasiṣṭha-, Āpastamba-, Baudhāyana-, Viṣṇu-, and Gautama- sūtras.

The Gṛhyasūtras include: Āśvalāyana, Kauṣītaki, Śāṅkhāyana associated with Ṛgveda; Gobhila, Khādira, Jaiminīya, Kauthuma associated withSāmaveda; Baudhāyana, Hiraṇyakeśī, Mānava, Bhāradvāja, Āpastamba, Vādhūla, Kapiṣṭhala Kaṭha associated withKṛṣṣa Yajurveda; Pāraskara, Kātyāyana, associated withŚukla Yajurveda; and Kauśika associated withAtharvaveda.

The Śrautasūtras include texts like Āsvalayana, Śāṅkhāyana, Lāṭyāyana, Drāhyāyana, Jaiminīya, Baudhāyana, Hiraṇyakeśī, Bhāradvāja, Āpastamba, Kātyāyana, and Vaitana.

Finally, the Śulba-sūtra Kalpa texts include Baudhāyana, Mānava, Āpastamba, and Kātyāyana.

Consolidation And Further Expansion Of Kalpas

A consolidation and further expansion of the Dharmasūtras andGṛhyasūtras of Kalpa are a group of eighteen primary texts called Smṛtis and eighteen secondary texts called Upasmṛtis. The smṛtis include the texts of Manu, Yajñavalkya, Parāśara, Viṣṇu, Vyāsa, Dakṣa, Likhita, Atri, and many others.

Āgamas are the consolidation and further expansion of the Śrautasutras andŚulbasutras of Kalpa. They include numerous and voluminous texts dealing with the temple tradition — construction, art and architecture, iconography of the images, as well as the daily, fortnightly, monthly, and annual rituals and festivals observed in the temples. Above all, they discuss the underlying philosophy of the entire system. The Āgama literature divides into Śaiva (pertaining to lord Śiva); Vaiṣṇava (pertaining to lord Viṣṇu); Śākta (pertaining to goddess Śakti); Bauddha; and Jaina Āgamas.

The Śaiva Āgamas are Raurava, Mukuṭa, Kāmika, and Vātula. The Vaiṣṇava Āgamas are Pañca-rātra Agamas, Sāttvata Saṃhitā, Ahirbudhnya Saṃhitā, and Lakṣmī Tantra. The Śākta Āgamas are Śāradā-tilaka, Tripurā-rahasya, and Varivasyā-rahasya. These Āgamas are by no means exhaustive.

Purāṇa And Itihāsa

Amarasimha (fifth or sixth century CE) defined a Purāṇa as having five characteristic topics (pañca-lakṣaṇa):

- The creation of the universe

- Its destruction and renovation

- The genealogy of gods and patriarchs

- The reigns of the Manus forming the periods called Manvantaras.

- The history of the Solar and Lunar races of kings

Purāṇas consist of stories to educate ordinary people on many topics like famous people, rituals, pilgrimages, festivals, arts, sciences, and so on. They deal with geography, local traditions, history, and folklore with great spiritual insight. There are eighteen Mahāpurāṇas and eighteen Upapurāṇas. The Mahāpurāṇas include the Brahma Purāṇas (Brahma, Brahmāṇḍa, Brahma Vaivarta, Mārkaṇḍeya, Bhaviṣya); Vaiṣṇava Purāṇas (Viṣṇu, Bhāgavata, Nāradīya, Garuda, Padma, Varāha, Vāmana, Kūrma, Matsya); and Śaiva Purāṇas (Śiva, Liṅga, Skanda, Agni).

The Purāṇa literature also includes Sthalapurāṇas that pertain to local traditions in different places, taking elements from the local folklore and from the traditional stories of the Purāṇas.

The Itihasa are the famous epics of India—theRamāyaṇa of ṚṣiValmikī and theMahābhārata of Ṛṣi Vyāsa. These literally translate into our ‘history’ but are stories finally with metaphysical, allegorical, and philosophical insights targeting individual liberation. The spirit of the Upaniṣadik message and the four purposes of life – especially Dharma – run throughout the two most important Itihāsas. The Bhagavad Gītā forms one component of the huge corpus of the Mahābhārata.

Darśana

Darśana, or ‘point of view’ is the English equivalent of philosophy, though with different connotations. There are six orthodox schools of Indian philosophy (Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Sāṅkhya, Yoga, Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, and Uttara Mīmāṃsā) and three non-orthodox schools (Jaina, Bauddha, and Lokāyata or Cārvaka).

TheNyāya (epistemology) and Vaiśeṣika (ontology) systems largely deal with the physical level. The Sāṅkhya (method of reasoning) and Yoga (union of body, mind, and soul) systems largely deal with the spiritual level. Pūrva Mīmāṃsā deals with the preparation for philosophical pursuits and explains the philosophy of rituals; and the system of Uttara Mīmāṃsā deals with philosophical pursuit and gives means for transcending rituals. Each of the darśanas has a huge number of treatises and authors.

What Represents “Hindu Religion” And To Whom Do These Texts Belong?

These knowledge traditions are not the exclusive hold of any single country, faith, or community. The main point is that India had a huge corpus of literature covering all aspects of life by reflecting its own experiences and using its own metaphysics. The knowledge tradition had very exacting standards which led them to postulate the laws of motion and create perfect astronomical tables on the one hand; while on the other, for example, devise plastic surgery techniques for amputated noses. A metaphysics rooted in the Vedas formed the sound basis of our knowledge traditions.

The methodology was perfect, the encapsulation as short sūtras for easy remembrance was also advanced. Maybe, they did not reach the last stage of developing equational formulae because of Islamic invasions and colonialism. Following the Islamic invasions, the output, especially in mathematics, moved southward. European colonialism resulted in a change from production to protection of the generated knowledge. That became the sole concern of the intellectuals. However, over a period, the constant colonial onslaught, helped majorly by missionary narratives, put a stop to the knowledge output. Not only did the Brahmins become the villains of Indian society – the varna group which painstakingly fought to preserve the knowledge tradition – but wholesale, the Indian population grew ashamed of themselves for being so “primitive and superstitious”.

Independence should have been a break; but unfortunately, a heavy colonial consciousness colored our intellectuals, academics, and educated Indians who parroted yet the same understanding as the colonizers. Very few turned to question the colonial narratives. The truth of their narratives seems obvious because the proof appears to be their “scientific and technological might”. When “reason” became supreme as a lens to study non-western cultures and their knowledge traditions, the latter appeared hazy, ambiguous, confused, and only seemed to have that odd achievement by pure chance.

Knowledge comes through three levels of mind: instinct, intellect, and intuition. Śrī Aurobindo says that the highest knowledge state of the civilization in the past was that of intuition where the Rṣis played a primary role. The age of Reason (or intellect) was in fact a degeneration of the state of civilization. This is the state of modern science, where metaphysics addresses at the level of intuition to produce knowledge.

Brahmins As Villains

Indian Knowledge Systems belongs to anybody identifying as a human being; and more so, as an Indian. The knowledge base of Indian scriptures and texts is accessible to everyone. Knowledge always is the supreme divine in Indian traditions and the story of villainous Brahmins withholding this knowledge is simply a colonial narrative which we internalized. The learning of Vedas and preservation of Vaidika ritual was more a matter of duties rather than any “hereditary-based-rights”. Twisted narratives of liberalism and individualism raised such questions.

Anti-Brahminism has a relentless story since the 17th century European reports of missionaries and travelers. No evidence seems to change this core narrative, even as the auxiliary hypotheses and explanations undergo modifications, as pointed out elegantly by Jakob De Roover. As he writes, every research program consists of three elements:

…a “hard core” of basic theses and assumptions; a “protective belt” of auxiliary hypotheses that surrounds this core; and a “heuristic” or problem-solving machinery consisting of sophisticated techniques.

Scientists regularly encounter observations that conflict with a theory’s predictions and other types of problems. However, there is no discarding of a research program simply because it faces some set of anomalies; instead, its protective belt allows the scientists to cope with these problems by immunizing its hard core against falsification – by generating new auxiliary hypotheses.

The basic assumptions about the religion of the Brahmin and its hold over society and education are part of this program’s hard core, whereas other claims concerning Aryan invasion, racial superiority, and the varna ideology are part of its protective belt. The latter ideas form a more flexible set of auxiliary hypotheses, which scholars can modify and revise in the face of anomalies, to protect the research program from refutation. Indeed, this has happened regularly, not only during the past decades, but also in the centuries before. Between the 17th and the 21st centuries, in the face of empirical and conceptual problems, the auxiliary hypotheses moved, as an example, from an Aryan invasion and conquest to peaceful migration and contact. But the hard core of assumptions concerning stories of a tyrannical priesthood and closing off the knowledge to other people in society remained immune against falsification.

Śrī Aurobindo significantly says –

When it is spoken of as a Brahminical civilisation, the phrase cannot truly imply any domination of sacerdotalism, though in some lower aspects of the culture the sacerdotal mind has been only too prominent; for the priest as such has had no hand in shaping the great lines of the culture. But it is true that its main motives have been shaped by philosophic thinkers and religious minds, not by any means all of them of Brahmin birth. The fact that a class has been developed whose business was to preserve the spiritual traditions, knowledge, and sacred law of the race, – for this and not a mere priest trade was the proper occupation of the Brahmin – and that this class could for thousands of years maintain in the greatest part, but not monopolise, the keeping of the national mind and conscience, and the direction of social principles, forms, and manners, is only a characteristic indication.

PART 2

Ontology In Western And Indian Descriptions: Indirect Realism And Direct Realism

Ontology (‘onto’- real or existence; ‘logia– science) studies what is real and what exists. When it comes to perceiving objects in the external world, the standard Western paradigm is that light falls on an object first. This reflected light enters the eyes and falls on the retina, from where neural impulses travel via the nerves to a region of the brain. Here, the image gets a reconstruction, and the person ‘sees’ the object. The same sequence is true for all the other senses too, like hearing, touch, smell, and taste. This is the ‘stimulus-response theory of perception,’ a stimulus of some sort evoking a response inside our brains through an intermediate causal chain. Of course, there is difficulty in explaining how an internal image inside the brain projects to the outside world.

Hence, in effect, what we perceive in the external world is not as it really exists but how the interpretation occurs in our brains, which depends on our endowed senses. This is Representationalism – the perceived world as only an internal representation of an external world; hence, it is an indirect form of reality. What exists outside is never known.

What is known is the reconstruction of neural impulses in the brain. The world outside is not a true world in this sense. In Kantian philosophy, the original unknown is the ‘noumenon’ (in modern parlance, ‘the non-linguistic’ world), and the known constructed reality is the ‘phenomenon’. Representation is the contemporary scientific view that gets the term ‘Scientific Realism’ or ‘Indirect Realism’ and forms the basis of both philosophy and neuroscience.

In contrast, Indian philosophy for thousands of years has been clear on its stand on ’Natural Realism’ or ‘Direct Realism’. All six systems of Indian philosophy, with some minor variations, propound an active theory of perception where the perceiver is central in the scheme of things. The perceiver goes out and reaches the object in the world. This is the ‘contact-theory of perception’ of Indian philosophy in contrast to the ‘stimulus-response theory of perception’. Contact with the object by the perceiver gives direct information about the world as it exists. Hence, the external world, as seen or heard, is an actual world in its reality and not a construction.

This establishes the role of pratyakṣa, or direct perception, as a valid pramāṇa, or means of knowledge. This contrasts with Western philosophy, where the world can never be known; hence, perception is never a valid source of knowledge in western traditions. This is the driving conclusion of Śrī Chittaranjan Naik in his first classic book, Natural Realism and the Contact Theory of Perception.

Western Philosophy And The Problem Of Ontology

Ontological studies are divided into two groups: mind-independent and mind-dependent. One believes that material processes are real and that reality exists independently of the observer. In this position, the world exists independent of our perceptions of it. The other group believes that the immaterial mind and the generated consciousness are the true reality, and the world is dependent on the observer’s mind.

In the overwhelming contemporary position, which says that the world is mind-dependent, there are two further subgroups of explanations: a) Representationalism (Scientific Realism or Indirect Realism) believes that the perceived world is only an internal representation of an external world; hence, it is an indirect form of reality. The real world remains unknown. b) Idealism believes that the world we perceive is a construction. The world has no existence independent of the mind or our subjective perceptions of the world. Thus, in the “mind-dependent world” position, the mind either constructs an image of an existing outside world or the world itself with no outside world at all.

If there is a mind-dependent world, then what is the ontological status or the true reality of the world? All we ever know is the ‘phenomenon’, with the true ‘noumenon’ always unknown.

By the beginning of the 20th century, there was an impasse in the philosophical world, which was the ‘problem of the external world’: The perceived world appears to be external to us and to exist independently of our minds. Yet, what we perceive are secondary qualities, as presented to our sensory faculties and their specific powers. They are not the primary qualities that belong to the objects themselves. All Representationalist systems cannot thus effectively address the topic of ontology (reality), as the real world (noumenon) is always beyond our capacity of comprehension.

Even the intervening medium, such as space or air, through which data transmits from the object to the mind, would have existed prior to the appearance of the representations. In other words, they are noumena. In which case, how can we speak of the ideas of motion, medium, space, time, and their relations when they are all categories applicable to phenomena? The stimulus-response theory of perception presents a riddle. If we do not possess the capacity to speak of the real world external to us (or the noumenon) in meaningful terms, how would we indeed be able to investigate the topic of ontology? In the field of Western philosophy, this problem is unresolved to this day.

Consciousness In Indian Philosophies

Indian and western philosophies distinctly differ on many issues. Fundamentally, Consciousness (also known as the Self, Puruṣa, Cognizer) is primary in Indian traditions; it is secondary to matter in western traditions. Consciousness does not include a deep sleep state in western definitions. In Indian traditions, the three brain states are the awake state, the dream state, and the deep sleep state, and ‘Consciousness’ is transcendental to all three. Mind and matter are different from this Consciousness.

Indian philosophy makes a clear distinction between the Self and mind-matter as two distinct identities. Mind and matter belong to the same category. In Indian traditions, the category of the cognizer is the Self (or Puruṣa), whose characteristic feature is consciousness. Hence, Self, consciousness, cognizer, and Purusha belong to the same category of sentience. Mind-matter, also known as prakṛti and always insentient (inert or having jaḍatva), belongs to the distinct category of the cognized.

Mind and matter are the two modes in which objects of cognition appear, revealing legitimate objective reality.

In Indian tradition, the nature of an object never changes. When the circular shape of a coin changes to a square one, the law of identity (a thing as itself) stays constant, but it is “time” that presents the dynamism and change. Thus, Bhartṛhari’s Vākypadīyam says that the creative power of Reality is Time.

Unlike the western notions of an unknowable noumenon (original), where the perceived world loses its intrinsic character; in Indian philosophy, the term ‘unknowable object’ is devoid of reference (vikalpa), and is an illegitimate verbal construction (like the son of a barren woman). In Indian traditions, a conceived object cannot be unknowable, and if it is unknowable, there is no conceiving.

In this overarching principle, where the perceived world is independent of the mind, we return to the one world that we all experience and live in.

Indian Approach To Ontology: Contact Theory Of Perception And Natural Realism

What is the ‘nature of the world’ as it appears through the theories of science? Śrī Chittaranjan Naik elaborates on the Indian idea of perception in his book Natural Realism and the Contact Theory of Perception. Firstly, there is no distinct thing in science called ‘the seer.’ Secondly, science postulates an elaborate mechanism from the object to the brain by which perceptions of objects occur.

As seen earlier, the very nature of this postulated mechanism makes the things seen in the nature of images, not the objects themselves. There are philosophers who stick to the representation of the world as images in the brain and yet hold that this is the true and actual world as it is. These are the Naïve Realists. And the philosophy that holds the perceived world to be the real world is ‘Naïve Realism.’

All traditional darśanas begin with an explanation of the pramāṇas. A pramāṇa is a means of obtaining knowledge about an object. The object known by means of a pramāṇa is called the prameya. Knowledge of the object is called prama. There are three basic pramāṇas (and three secondary ones which we shall see later) in traditional Indian philosophy. They are āgama (scripture), pratyakṣa (perception), and anumāna (inference).

Prama, or knowledge of an object, is not a distinct entity that stands between the subject and the object. It is a qualification of the subject, the knower. _Now, there is a distinct mark of the _prameya, or object, in traditional Indian philosophies that is missing in science and Western philosophy. This mark is the mark of ‘being seen’ or the mark of ‘knowableness’. This point is so vital that if we fail to recognise it, it is likely to lead us into such a position that we would not be speaking Indian philosophy at all, writes Śrī Chittaranjan Naik.

The mark of ‘being seen’ is a mark of prakṛti, or nature. In Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, Uttara Mīmāṃsā (Vedānta), Sāṅkhya, and Yoga, the prameya is seen _as distinct from the _seer. This feature of objects as being ‘the seen’ is held by Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika schools as well. In Navya-Nyāya, after defining the seven kinds of padārthas (word-objects) – substance, quality, action, universal, particular, inherence, and non-existence – it states that the common feature of all these seven categories is ‘knowableness’.

This feature of objects being ‘the seen’ finds expression in the philosophical tenet that there is a contact between the seer and the object when the object is seen. This contact is called sannikarṣaṇa, and the form that the (reflected) consciousness of the seer assumes in seeing the object is called ‘vṛtti.’ Thus, the entire world is “the seen”, and it is seen directly ‘as it is’ without there being any extraneous mediating factor between the seer and the seen.

So, according to traditional Indian philosophies, the object known is neither a mere presentation of something else that may be the real object (as in science) nor is it reducible to something lesser than what it presents itself as (such as a mere idea or artifact of the mind). An object is that which stands in front of Consciousness in the cognitive act of perception. The world of Indian philosophy is not the world of Naïve Realism, nor is it the ideated world of idealism.

If we must find a name for it, it may be called the world of Direct Realism – a world as it is that presents directly to Consciousness in an unchanged manner.

The Embodiments Of The Self, Perception, Liberation, And Rebirth

The Self, being of the nature of consciousness, is self-effulgent. And it has, by virtue of its self-effulgence, the capacity to reveal objects directly and instantaneously. The absence of ubiquitous perception indicates that there is some primal covering over the Self, which obstructs its natural revealing power from revealing the objects of the world.

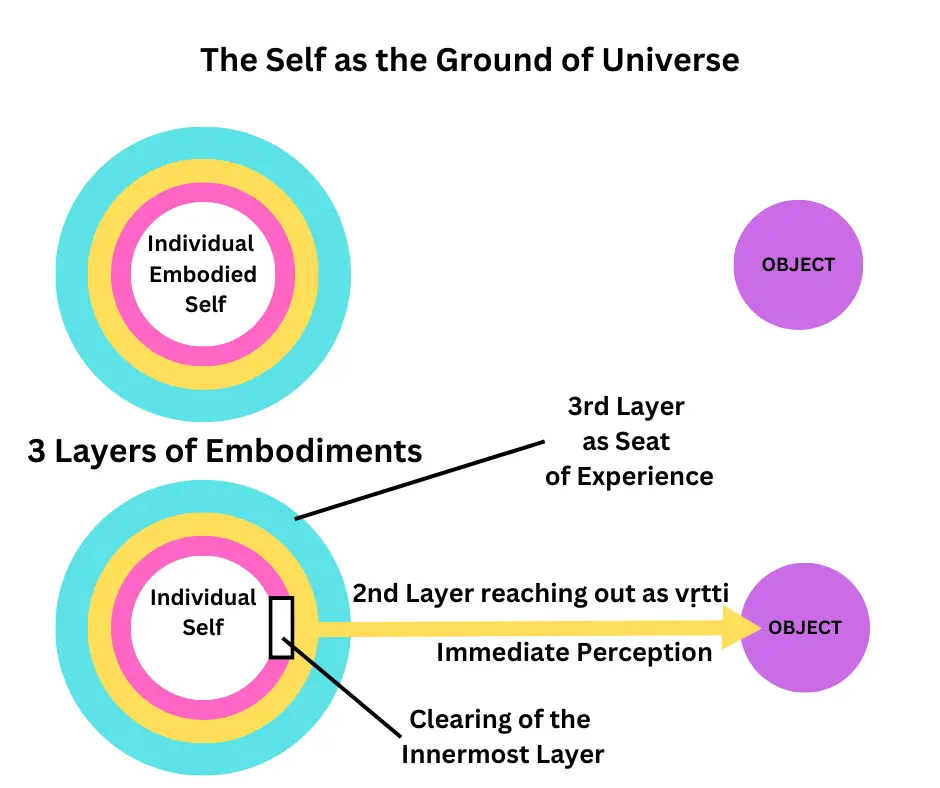

In Indian philosophy, this obstruction of the Self is the body itself. Embodiment is three-layered. At its most primal layer, the covering is essentially of the nature of sleep. The middle layer is the layer of ideation, the realm of mind. The outermost layer is the layer of the gross physical body through which the embodied self comes to be a creature in the world. The three layers are known as bodies with different names: mūla-śarīra (seed body), sūkṣma-śarīra (subtle body), and sthūla-śarīra (gross body), respectively.

The paradox of embodiment is that the embodiment of the self does not, in truth, exist. How can something arise in Consciousness – the ground of all the universe – and then contain it? The embodiment of the self comes about not through a spatiotemporal physical process, but through a cognitive condition whereby the Self becomes morphed into the body, as it were, and cognizes the body to be the self.

This erroneous idea is the mithya-jñāna superimposed on the Self and the body. This makes one see the body manifested in the realm of the world as the Self. An idea in the mind is the same as the body apprehended in the world as the Self. As seen before, the idea in the mind and its corresponding matter in the world are the same, appearing in two different modes of cognitive presentation.

The idea of the Self’s embodiment through a cognitive condition is central to Indian tradition; it forms a core tenet in all six darśanas, or systems of philosophy, though with slight technical variations. Embodiment is an erroneous cognitive condition; hence, right knowledge confers liberation. Embodiment persists so long as the erroneous knowledge continues.

Even when the physical body undergoes destruction, the notion of the body will continue to persist in the realm of the mind. The Self, still equipped with the power of thinking, would consider the destruction of the body a loss and crave to be in possession of a body. In the Indian tradition, this craving, along with the law of causation that bears upon the embodied jīvātma’s moral actions in its past births, results in the rebirth of the Self in another body.

It is within this three-fold structure of embodiment that we must look for the instruments of perception. For, even though the Self has the capacity to reveal objects by virtue of its intrinsic effulgence, maya obstructs its power of revealing. The innermost layer is the layer in which the clearing in the covering of maya appears; the middle layer is the layer that actively reaches out to the object with the help of the instruments of perception; and the outermost layer comprising the physical body is the layer that constitutes the seat of experience.

Seen And Unseen Causes, Karma, And Experiencing The World

Perception and experience of the world occur to the individual self when there is a clearing in the veil of maya. The clearing appears by the Wheel of Causation operating in nature, or prakṛti. The causality that operates in them is of two kinds: the seen and the unseen. The causality that operates between physical objects is of the seen kind. The nature of the objects themselves determines this.

The causality of the unseen kind is that in which the immediate effect of an action is invisible. But all actions of conscious agents do not produce unseen effects; it is only those actions that have a moral dimension to them that result in unseen effects. The effect of an individual’s moral action is apūrva, meaning that what did not exist before is newly born. It is the result of either a virtuous action or a morally transgressive action, and its effect surfaces at a future time when the conditions for it to fructify are satisfied.

The total of the unfructified apūrvas of an individual is the individual’s adṛṣṭa, also referred to as past karma since it is the net balance of the accumulated effects of past actions held in store for future fructification. Śrī Ādi Śaṅkarācārya, in commenting on the Bṛhadāraṅyaka Upaniṣad, in the context of a man’s rebirth, explains it as follows:

He has adopted the whole universe as his means to the realization of the results of his work; and he is going from one body to another to fulfill this object.

And as Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa says,

A man is born into the body that has been made ready for him.

There is perfect synchronicity between the world that an individual being perceives and the individual’s past karma. The Law of Causation (Dharma Cakra, or Wheel of Dharma) projects the manifested world in accordance with the collective past karmas of individual beings. An individual within this collective perceives that part of the manifested universe that his or her past karma entails him or her experiencing. The physical body is the seat of this experience, and the regulated uncovering of the veil of maya – the veil of sleep under which the individual being transmigrates – determines that part of the world the individual being will experience.

The Law of Causation does not violate the nature of objects. It is the nature of fire to burn and water to flow, and these natures are part of the law. The unfolding of the manifested world therefore does not violate the physical laws that operate between objects by virtue of their physical natures (dharmas). The causal force of Dharma Chakra acts as an unseen ordering force that determines the boundary conditions of the objects of the world. This is the overarching Law of Causation that the Indian tradition espouses, and it comes from śabda-pramāṇa, the means of knowledge by which reality beyond the realm of the senses may be known.

Advaita And Nyāya

There are philosophers who argue that there can be no means to know whether there are real objects in the world, given that everything we experience arises in our minds and is contained in the mind itself. This is a philosophical position termed “Idealism.” There are many variants of Idealism, from the kind first proposed in the West by Berkeley (1685–1753) to the later variants known as Phenomenology and Existentialism, but they all fit into the broad category called ‘Idealism’, as they hold the world to be born out of subjective ideations and belief systems. The terms ‘Naïve Realism’ and ‘Idealism’ are fine when used to refer to certain philosophies of the West. But Śrī Chittaranjan Naik writes that it is wrong to label Nyāya as a kind of ‘Naïve Realism’ or ‘Advaita’ as a kind of ‘Idealism’ – which many authors fail to realize.

Advaita is not Idealism because it negates both the mind and the world. And, at the same time, the mind and the world are different. Advaita does not negate only the world and leave aside the mind to say that the world is ‘mind.’ There are twenty-four tattvas defined in Vedānta, and only four of them are internal instruments (antah-karaṇas _comprising ahaṅkāra, citta, buddhi, and manaḥ),_ whereas the rest are external objects. The attributes of the internal instruments cannot transfer to the objects of the world. The world is not ‘mind’.

The objects of the mind, i.e., ideas and thought, have the characteristic of being determined by the individual’s will, whereas the objects of the world do not have the characteristic of being so determined. One cannot cook food by merely thinking about the food. In Advaita, the relations between words and objects are eternal, and each word denotes a specific kind of object with specific attributes. Without understanding this basic tenet of Advaita, it is wrong on the part of those authors to label Advaita as Idealism and thereby cause confusion.

Some use the oft-repeated criticism that Advaita’s position is that ‘nothing is real’ from a profound misunderstanding. The complete expression is brahma-satya, jagan-mithya. The subject matter of Advaita is Brahman and not the world, and thus, jagan-mithya is never an isolated proposition. The locution of jagan-mithya (world illusion) is always with the locution of Brahma-satya (Brahman Reality).

A discussion of the world, excluding Brahman, however, makes the world satya, or real. Denying the reality of the world, which excludes Brahman, reduces it to an unacceptable Nihilism. Hence Ādi Śaṅkarācārya takes the position that the world is real when refuting Vijñānavāda and other Idealist schools of Buddhism which deny Brahman. Modern proponents of Advaita Vedānta overlook this vital point.

Indeed, in both Advaita and Dvaita, the relation between Brahman and the world is the relation of Bimba-Pratibimba, the object and its reflection. There is a common misconception arising about the ontological (reality) status of the reflection seen in the mirror. The reflection of an object, say of a flower, seen in the mirror, is unreal because the reflected object is not a real flower. However, the object called ‘image of a flower’ is real because the reflection is truly an image of a flower. In other words, the object is not true to the name ‘flower’ but it is true to the name ‘image of a flower’.

In this world comprising various objects, all these objects may be the reflections (pratibimbas) of Brahman but they are true to the names they are known by. Hence, they are real. The world objects are all pratibimbas, having no existences by themselves but with their existences derived from, and entirely dependent on, the Bimba, which is Brahman, the Supreme and Sole Independent Existence. Without Brahman, the universe and its objects have no capacity to exist, just as in a mirror the reflections have no capacity to exist without there being objects.

Nyāya is not Naïve Realism. This is a caricature that has no bearing on Nyāya. The entire dichotomy between ‘images seen in perception’ and ‘unknowable objects out there in the world’ has been created by an incoherent hypothesis that perception takes place through the mediating mechanisms of the sensory network and the brain. The Nyāya (and Vedānta) theory of perception is based on the principle of contact between the subject and object, in which there is no chance of the reality of the world becoming ‘naïve.’ Nor is there in them a chance of the world becoming something other than what is seen. Therefore, the application of the term ‘Naïve Realism’ to Nyāya betrays a lack of knowledge of Nyāya.

The Perceptual Process In Indian Traditions

At the most primal level, perception is by the removal of the covering of maya over the individual self. In Advaita Vedānta, the covering of maya over the self is avidya or nescience. The removal of the nescience to allow the conscious light of the self to reveal external objects constitutes perception.

In the Indian tradition, perception is an active process in which the Self, as the Inner Controller, drives the senses towards their objects in accordance with the individual’s adrṣṭa.

On the removal of nescience, the self’s conscious light streams out to the object and envelopes it.

In this process, the mind assumes the form of the target object of cognition during a conceptual act. The form that the mind assumes in presenting an object to cognition is a vṛtti. The mind forms a vṛtti both when it constructs an object purely as a mental phenomenon as well as when it contacts an external object and envelopes it and assumes the form of the object. Perception is thus a composite process in which the self, the mind and the sense organs together participate to establish a contact with the object. The Nyāya text Tarka Saṅgrahaḥ explains it as follows: The self (ātman) contacts the mind (manas), the mind with the organ (indriya), and the organ with the object (viṣaya), and then perceptual knowledge takes place. This is a direct perception of the object and its quality too.

In Indian tradition, the attributes perceived of objects, such as color, taste are not subjective qualities but are objective qualities inherent in the objects themselves. This is in sharp contrast to the viewpoint of Contemporary Western tradition wherein they are subjective phenomenal qualities. In the Indian theory of perception, there is no transformation of the object in the process of presentation. Once the mind and sense organs contact the object and assume the form of the object by forming a vṛtti, there would be a conjunction of the mind, the sense organ, and the object at the very location of the object. There would be nothing in between the self and the object to hinder the conscious luminosity of the self from revealing the object in its true form.

The contingency of the mind and sense organs as distorting filters arise only when they have a defect hindering it from assuming the form of the object.

When such defects of the sense organs or the mind are absent, there would be nothing present in between the self and the object that can prevent the perception from revealing the object in a transparent and true manner. The perception of an object is in the actual spatial location where it exists and is instantaneous. There is no time-lag in perception. Śrī Chittaranjan Naik proposes an interesting experiment to prove this. One can refer to the wonderful book Natural Realism for further details.

In the case of touch, taste and smell, the (subtle) organs do not move out of the body, so the perception takes place at the location of the physical sense organs themselves when the objects come into contact with the physical sense organs of the gross body; whereas in the case of visual and auditory perceptions, the indriyas move out of the physical body to make contact with the object in external space.

While there are minor variations between the darśanas about the technicalities of perception, all the darśanas hold that perception takes place due to the contact of the (subtle) sense organs with the object. There is uniformity regarding perception being direct and revealing the object in its actual form through the contact of the consciousness with the object through the instrumentality of the sense organs and mind.

Such contact is instantaneous since the consciousness that appears within the body is the same Consciousness that exists without the limiting adjuncts of the body and which is in conjunction with all objects.

Hence, perception is nothing more than the removal of the covering of maya over the individual consciousness to reveal the conjunction that already exists with the object.

PART 3

Knowledge (Epistemology) In Western Definitions

It is surprising that western philosophy, which prides itself on scientific innovation and technology, does not seem to have a proper theory of knowledge or epistemology. It has hardly spent time on developing the meaning of knowledge and methods to acquire it. The standard definition of knowledge in western philosophy is justified true belief (JTB). In 1963, American philosopher Edmund Gettier presented two famous counterexamples to the JTB account of knowledge. These two counterexamples came to be known as Gettier problems, along with a few more cases added by philosophers to the original two.

Gettier problems arise when there is a disconnect in the relationship between justification and truth.

A famous example for the reader is as follows:

Standing outside a field, X sees inside the field what exactly looks like a sheep. Let us call it A. X now has the belief that there are sheep in the field. He is right because behind the hill in the middle of the field there is a sheep, though he cannot see it. The justification of this belief is upon looking at A. But A is actually a dog disguised as a sheep. Hence, X has a well-justified true belief that there are sheep in the field. But is this belief, knowledge?

As per the standard definition, if a person holds a belief on justified grounds and that belief is true, then that person has knowledge. The counterexamples provided by Gettier show that the belief is true (a given), but the person’s reasons, though justified, cannot turn the belief into knowledge. It was plain luck that made the belief true. The counterexamples thus disprove the ‘justified true belief’ definition of knowledge. But there are problems in this account of both knowledge and the counterexamples that appear to undercut the definition of knowledge.

Śrī SN Balagangadhara Rao (Balu ji) in Cultures Differ Differently (Knowledge, Bullshit, and the Study of India) shows that the Gettier examples do not and possibly cannot challenge the definition of knowledge. Problems appear when we correctly interpret these examples. The role played by the indexical terms (meaning the reader, ‘you’ or we) in making the sentences true or false appears neglected in Gettier problems. Who proposes justifications for X’s beliefs? We do. It is we again who have justified true beliefs about X’s beliefs. Thus, we not only advance a claim about X’s epistemic state but construct examples in such a way that makes our claims true and justified.

However, X’s beliefs are examples of ignorance and not knowledge. Balu ji explains that “ignorance” is the negation of “knowledge.” With this move, X is in an epistemic state of ignorance, where the beliefs are wrong, and the justifications are false.

The Gettier problem arises because knowledge and ignorance are made to range over the same object in the same way at the same time and place for the same person. This move generates the ‘problem’.

In the Gettier examples, we have two different entities, ‘X’ and ‘us’, in opposing epistemic states (of ignorance and knowledge). X does not and cannot have knowledge because of ignorance (which is the negation of knowledge) and false beliefs (the negation of truth).

How could X then be said to have a ‘justified true belief’, which the definition demands? But we do have that knowledge both about the objects (the fake and real sheep) and about X’s belief. Thus, we have knowledge that X does not. Contrary to the examples, neither we nor X face Gettier’s problem. ‘Ignorance’ is when we have false beliefs and inadequate justifications.

Balu ji summarizes:

Gettier problem’ does not arise from defining knowledge as justified true belief, and the constructed philosophical examples are no counterexamples. The ‘problem’ has its roots in making ignorance mean its opposite, namely, knowledge. This move has three elements. One: ignoring the fact that the examples contain indexical terms. The other two are epistemic sleights of hand: the first draws the reader into the picture by setting up examples and ignoring the reader in the subsequent analyses; the second by equivocating about the meaning of ‘justification.

Indic Theory Of Knowledge: The Role Of Pramāṇas

Knowledge is the supreme ideal in Indian traditions. One of the attributes of Brahman, or the Self, which is the ground of the universe, is knowledge, and hence the pursuit of knowledge is the most divine pursuit in human endeavors. Indian texts developed an extensive theory of knowledge. Without such a theory, we could not have produced the enormous amounts of literature covering all aspects of life in the material (aparā) and spiritual realms (parā).

Any knowledge must have a certain means of acquiring it. Pramāṇa (proof or a valid ‘means of true knowledge’) plays an important role in Indian philosophical traditions. Ancient texts identify six pramāṇas whose variable acceptance and rejection form a basis for classifying thought systems. The first three are the main ones, and the other three are auxiliaries. These are:

- Perception or direct sensory experience (pratyakṣa)

- Inference (anumāna)

- Testimony of reliable authorities (śabda)

- Comparison and analogy (upamāna)

- Postulation and derivation from circumstances (arthāpatti)

- Non-perceptive negative proof (anupalabdhi)

Materialism (Lokāyata or Cārvāka) holds only perception as a valid pramāṇa; Buddhism, perception and inference; and Jainism, perception, inference, and testimony. Mīmāṃsā and Advaita Vedānta hold all six as useful means of knowledge. The practical aspects of Yoga and meditation are acceptable routes in all systems (except Cārvāka) to access knowledge and finally reach the state of liberation.

As Śrī Chittaranjan Naik says, traditional Indian philosophies are darśanas, not speculative philosophies. Traditional Indian darśanas are not something derived from basic principles to finally arrive at a conclusion.

As Naik says:

A Darśana is a Single Vision in which all its elements, including epistemology, ontology, metaphysics, the practice, and the fruits of sādhanā, are like various organs that form a single integral whole. Each of the traditional philosophies, or Darśanas, is eternal and part of the Vedic structure. That is why they constitute one of the fourteen branches of learning (vidhyāsthānas) known as Caturdaśa Vidyās. ‘Darśana’ strictly is not synonymous with philosophy.

In the West, scientific propositions have a criterion of physical verifiability; however, philosophy in the West has a different criterion. It is for this reason that philosophy earned a notoriously bad name in the early years of the twentieth century, when the entire field of metaphysics became ‘nonsense.’ The attack against philosophy came from the ‘Analytical Philosophers.’ Hence, in the absence of either empirically verifiable propositions or derivations out of already defined terms, metaphysical statements became meaningless. Since metaphysics, philosophy, ethics, religion, and aesthetics are all of this nature, the only task that remained for philosophy was that of clarification and analysis. They concluded that the propositions of philosophy are linguistic, not factual, and philosophy is a department of logic. Based on such assertions, Analytical Philosophy swept aside two millennia of lofty human thought into the dustbin of ‘emotive’ thinking.

However, Western philosophy had failed to provide a sound basis for epistemology (the theory of knowledge), and it became a complex maze of verbiage that ultimately led to the discrediting of everything metaphysical and of philosophy itself, says Śrī Chittaranjan Naik (apauruṣeyatva of the Vedas). The justified true belief definition of knowledge is the basis of its knowledge, and Gettier showed many problems with this notion by providing counterexamples. It is once again surprising to note that the West, which prides itself on so many scientific and technological developments, does not have a proper theory of knowledge. Its criteria for scientificity have also repeatedly undergone revisions.

In traditional Indian philosophy, assertions about the objects of the world are grounded either in perception or in inference. Hence, there is no scope for these assertions to stray into speculative thought. If they do stray, it is only due to the incorrect application of the pramāṇas. And when it comes to assertions about things that lie beyond the range of the senses, the assertions are grounded in scriptural sentences (śabda) and in inferences that depend entirely on these scriptural sentences. If they do stray here too, it is again due to an incorrect understanding of the scriptural sentences, or the inferences drawn from them.

Yoga And Knowledge

Yoga is obtaining knowledge of the immortal Self, which frees man from the shackles of prakṛti. All orthodox and non-orthodox schools (except Cārvāka) give importance to Yoga and meditation in their schemes of things. The first five aṅgas (parts) of Yoga are the preparations for the higher states: yama, niyama, āsana, prāṇāyāma, and pratyāhāra. The first two (yama and niyama) are for control of desires and emotions; the next two (āsana and prāṇāyāma) eliminate disturbances from the physical body. Pratyāhāra detaches the sense organs from the mind, thus cutting the external world and its impressions from the mind.

The last three aṅgas after this preparation are dhāraṇā, dhyāna, and samādhi. Dhāraṇā is confining the mind within a limited mental area; dhyāna is uninterrupted flow or contemplation towards an object of meditation; and the final state is samādhi, where there is consciousness only of the object of meditation and not of the mind. The mind dissolves into the final state of samādhi. These last three together constitute the samayama, and this can be performed on any object.

Can these states give rise to knowledge of the mundane world? The Yogic answer is affirmative at one level and negative at another, as Śrī Ramakrishna Puligundla explains in his classic Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy. Samādhi has progressive savitarka and nirvitarka stages, according to Patanjali. In the savitarka state, knowledge occurs at three levels: śabda (based on words), jñāna (knowledge based on perception and reasoning), and artha (the intuitive knowledge of the object in its essence). In the nirvitarka final state, the yogī is one with the Supreme Consciousness. The savitarka state, especially the jñāna component, based on perception and reasoning, can construct conceptual knowledge.

According to Śrī Patanjali Mahaṛṣi, the yogī, who has reached the final state is infinitely perfect and is God. Therefore, there is nothing the yogī cannot know since there is instant cognition of anything with a complete mastery of the universe. The highest state cannot give rise to knowledge of individual objects, but the yogī, if he chooses to, can reach the corresponding states of consciousness, and attain knowledge of the world. Thus, the intellectual, perceptual, and conceptual knowledge (“phenomenon” of Kant) is available in the savitarka states, and the essence (or “noumenon”) of Kant is available in the nirvitarka state.

Science And Metaphysics

Science, by popular conception, seems to be the correct way of understanding the external world, whereas metaphysical thoughts appear to be other-worldly, mystical, or plainly superstitious. Thus, science triumphed over metaphysics as a solution for humanity. But can that be true?

Ananda Coomaraswamy wrote a century ago, “What then are the essentials, from the Indian point of view, that, for their intrinsic value and in the interests of the many sides of human development, are so important to preserve?

A few of them were:

- The almost universal philosophical attitude that contrasts strongly with that of the ordinary Englishman, who hates philosophy. Science is important, but there are wrong and right ways of teaching it. ‘Facts’ taught in the name of science are a poor exchange for metaphysics.

- The sacredness of all things— the antithesis of the European division of life into sacred and profane. European religious development excludes from the domain of ‘religion’ every aspect of ‘worldly’ activity. Science, art, sex, agriculture, and commerce are, in the West, secular aspects of life, quite apart from religion. In India, this was never so; religion idealized and spiritualized life itself rather than exclude anything from it

- Special ideas in relation to education, such as the relation between teacher and pupil implied in the words of guru and celā (master and disciple); memorizing great literature such as the epics, and embodying ideals of character; learning not to become a mere road to material prosperity; and the high emphasis attached to the teacher’s personality and presenceThis view is antithetical to the modern practice of making everything easy for the pupil.

Metaphysical conceptions are slighted in our modern world, while the scientific method is hailed as a panacea for all our ills, says Śrī Venkat Nagarajan in an incisive essay, False Supremacy of Science. This view has not been adequately challenged. Metaphysics has been relegated to mean a faith-based view of reality and is thus not considered worthy of respect.

As Śrī Nagarajan says:

Assumptions (i.e beliefs) and value judgements are at the root of all theories, whether they are scientific or metaphysical; therefore, Science is not worthy of a higher status than Metaphysics. They both approach reality from different perspectives; consequently, they cannot be compared. In fact, one could reasonably argue that they constitute mutually exclusive systems for understanding the nature of reality. Lastly, Science is not prescriptive; it does not tell a person what he or she should do to minimize his or her misery or maximize his or her happiness, given the nature of reality. A metaphysical system, on the other hand, is prescriptive; it provides an algorithm that can be followed for a person to minimize his or her misery or maximize his or her happiness.

The original argument was that only empirical evidence could validate scientific theories. Revolutionary changes in scientific theories have, however, established that empirical evidence alone cannot conclusively establish scientific theories. There is always a chance that a present theory can be falsified by a competing theory in the future, like the replacement of Dalton’s atomic model with Niels Bohr’s atomic model. The falsifiability criteria replaced the empirical evidence theory of science. Now, science is superior because, unlike metaphysical claims, a scientific theory can be falsified using evidence.

This argument also failed because a scientific theory or hypothesis is always linked to a series of supporting premises. Any falsifying evidence or observations can thus be falsifying at least one of the supporting assumptions and not the scientific theory itself. Then, an effort was made to argue that scientific theories can be shown to be conditionally true in a probabilistic sense based on empirical evidence, whereas metaphysical theories cannot. This argument also fell apart, as there may be many ways to derive the conditional probability, and there is no basis to argue that one way of deriving the conditional probability is correct.

All attempts to establish the supremacy of science over metaphysics have failed; consequently, one cannot make such a claim without making a value judgment that some form of intersubjective empirical verifiability is superior. Such a claim of supremacy would not be rooted in logic but rather in faith or belief, writes Nagarajan.

Science and metaphysics are different paradigms. Vedānta defines Being as Consciousness or the knowing Self, whereas science does not accept the notion of Being. The standard materialistic view of science is that atoms, molecules, compounds, matter, life, mind, and consciousness evolve in that order. Life, in evolutionary terms, is purposeless and accidental.

For metaphysical systems, life has meaning and a definite purpose. These systems are more holistic and give a great deal of importance to personal experience, emotions, and unexplained phenomena in explaining reality. Therefore, science and metaphysical conceptions of reality are mutually exclusive theories of reality that co-exist, and the choice of one or another is ultimately an individual’s prerogative.

Śrī Nagarajan concludes that no rational person can honestly argue that a scientific conception of the nature of reality is superior to metaphysical conceptions of the nature of reality. Such a person would have to acknowledge that assumptions and value judgements are at the root of all theories. All would have to submit to the fundamental axiom of logic that nothing is devoid of belief.

The Philosophical Underpinnings Of Knowledge Generation

Bhaskar Kamble (The Imperishable Seed) shows how most of the mathematics we take for granted has its strongest roots in India. Apart from the value of zero in mathematical operations, Brahmagupta, Bhāskara 1, Bhāskara 2, Mahāvīra, and the Kerala mathematicians laid the foundations in the fields of arithmetic, algebra, geometry, trigonometry, combinatorics, linguistics, and calculus starting in the 5th century of the Common Era.

Many of the ‘inventions’ and ‘discoveries’ of European mathematics finally, as the author shows, amount to who first and best plagiarized Indian knowledge systems. The Indian mathematical developments had many applications in the construction of buildings and temples, imbuing astronomy with great precision, and conducting navigation to distant lands by sea route.

Kamble discusses the basic metaphysical underpinnings of Hindu mathematics. Indian philosophy talks of parā vidyā and aparā vidyā, the knowledge of the higher Self and the knowledge of the external material world, respectively. It is one of the fundamental tenets of Indian knowledge systems that these two are not antagonistic to each other and are manifestations of a single unity in the form of Brahman. In such a stance, there is an intense spiritualization of every single aspect of aparā vidyā (all the ‘secular activities’) dealing with the material world. The antagonism between the ‘word of God’ and the ‘word of science,’ present in the Abrahamic traditions, never existed in Indian knowledge systems.

Most of the secular activities are finally in search of the unity that binds the parāand the aparā. In contrast, science, as popularized in Western culture, seeks unity only in the aparā, or material realm. There is a large body of skeptics, Kamble writes, who claim that Indians did not have a proper methodology while doing mathematics. Such claims are either based on ignorance, prejudice, or both.

Indian metaphysics has deep principles of the acquisition of knowledge (epistemology), which Western philosophy is still to acquire or formulate apart from its definition of knowledge as ‘justified true belief.’

It was only after contact with Hindu mathematics that Western mathematicians progressed further and started dealing with irrational numbers, negative numbers, zeros, infinities, and many other concepts. The Roman numbers hardly had the capacity to carry numerical operations, and for a long time, Europe was using the abacus to count, and that too only for positive integers. Though the formulas and original equations were terse and short, there was a tradition of detailed commentaries that explained the equations and formulas. These proofs in commentaries were an important component of Indian mathematics, but the critics conveniently ignored them.

The Self Or Brahman As The Basis Of Epistemology And Ontology

The Indian corpus of extensive literature cannot stand on flimsy epistemological grounds. Sadly, this aspect is rarely taught to us in our education systems, where modern science takes precedence. Any hypothesis in Indian traditions needs verifiability for acceptance (unlike the falsifiability criterion of science).

As Śrī Chittaranjan demonstrates in his book, On the Existence of the Self, the presence of human beings introduces something more than the behavior of material objects operating solely under physical laws. He shows how one needs to presuppose the presence of some entity, namely the Self, or soul, as a resident within the body of the human being.

The invariable correlation between goal-oriented actions and the presence of living beings (the origin of the goal-oriented actions) points to the existence of an element, namely the ātman, within living beings. Thus, purely physical causes and physical processes cannot explain goal-oriented actions. It follows, then, that the physical world does not form a causal closure. Naik meticulously lays the foundational basis of Indian logic based on Nyāya, with which he refutes Western philosophers arguing against the concept of soul and substance. He discusses in detail how Western philosophers such as Hume and Kant influentially discarded the notion of the soul, which led to many inconsistencies in Western philosophy.

The Question Of Method

The opposition to the Vedic tradition comes largely from those who espouse science. When it comes to the acquisition of knowledge, “reason” alone, a broad category, is an adequate tool. Science, for example, uses a specific reasoning method that is different from the reasoning methods used in philosophy. The central idea of science—physical causes alone can explain all things in nature—came from the Epicureans of Greece. Later, Francis Bacon (‘The Great Instauration’ and ‘Novum Organum’), Newton, and other scientists laid the foundation for the birth of science as we know it today.

In science, we begin with a proposition (a statement) that seeks to fit the facts of observed phenomena into a hypothesis. In doing so, the scientist uses reason to see that these facts fit logically into the meaning of the propositional statement. But science says further that this (propositional) statement must be physically verifiable. This is the key factor here. This principle of physical verifiability precludes the idea of there being any cause other than physical matter for the phenomena of the world. In contrast, there is no such constraint on philosophy by such ideas, and its propositions have a different criterion of verifiability than conformance to physical verifiability.

When discussing Vedānta, we deal with a ‘parā vidyā’ in sharp contrast to every other science or discipline in the world grouped under the name of ‘aparā vidyā’. Science endeavors to shed light on, among other things, how this universe originated and how life in the universe originated. Vedānta seeks to reveal the knowledge of a Truth by which billions and billions of cycles of creation and destruction are at once dissolved by an individual’s Self.

When we seek to know the ‘truths’ revealed by science, we use elaborately constructed tools, but when it comes to the Supreme Knowledge of Vedānta, why do we become so blasé that we feel free to disregard the methods that it advocates? Śrī Chittaranjan Naik questions whether such a predisposition on our part can be called ‘rational’?

The Trap Of Maya

When we strive to obtain knowledge about an object, there are three factors involved in the process of obtaining knowledge: the subject, the object to be known, and the internal instrument by which the subject obtains knowledge of the object. In both science and Western philosophy, the focus is entirely on knowing the object without regard to the nature of the internal instrument that we use to obtain knowledge.

In Vedānta, the situation is drastically different because it recognises that avidyā is the root cause of the jīva’s incapacity to obtain perfect knowledge. According to Advaita Vedānta, avidyā influences the perception of the world. Mūla-avidyā or the deep sleep that underlies the existence of a jīva, is avyakta, or unmanifest. It is the darkness of sleep that one ‘sees’ in deep sleep. It is the reason that when one wakes up from deep sleep, one says, ‘I knew nothing’. The ‘nothingness’ that one knows in deep sleep is the darkness that blocks the effulgence of the Self.

By its essential nature, the Self is self-effulgent with Consciousness. The deep sleep of the jīva obstructs this effulgence and presents the darkness of ‘nothing’. Even when a jīva wakes up, this sleep (bīja-nidrā) is present, and everything that it perceives is through the veil of sleep. That is why, when a man knows an object through perception, he still has the notion that he does not know it and builds theories to explain what the object is. The theories that one constructs to explain the object become superimpositions (adhyāsa) on the object.

In the words of Ludwig Wittgenstein, as Śrī Chittaranjan Naik explains, we look at the world through the nets of our theoretical constructs. Wittgenstein and his group in the field of Modern Analytical Philosophy tried to define a set of verifiability criteria for science. After striving for almost a decade, they abandoned the project. They recognised that the scientific propositions that form the initial working hypotheses of the scientists are already coloured by the symbolic framework of science. Thus, was born the idea of ‘theory-ladenness of observation’.

It is never possible for anyone to be completely free of theories when he or she looks at the world. Thus, the idea of our perceptions being coloured by avidyā is not a mere dogmatic assertion brought forth from the pages of Vedānta, but a similar notion is indeed evident in the phenomenon of ‘theory-ladenness’. This, then, is human predilection. The inner constitution of man is already coloured by the darkness of avidyā, and it presents a matrix of circularity from which it is difficult to escape.

The main point is that the inner instrument of cognition needs to be free of defects if we are to obtain knowledge. There is no attempt either in science or in Western philosophy to address this issue, whereas in traditional Indian philosophy, it forms a major part of the effort to acquire knowledge.

The Proof Of The Self

Śrī Chittaranjan Naik demonstrates the existence of Self in his second treatise by showing that in the presence of intention (icchā śakti), the probability of ordered complexity arising from simplicity approaches one. In the absence of intent, the probability of such complexity through blind and random combinations approaches zero. Some of the most famous discoveries of science (like gravity) were made by recognising the most commonplace phenomena staring at us all along. Similarly, we are looking at a power of the Self, or of intentional action, right in its face and are not recognising it.

Naik, in presenting this proof, sets up a verifiability criterion by which the truth of the proposition can become verifiable. As seen earlier, Indian philosophy stresses verifiability criteria and not falsifiability for validity. His proof establishes a correlation between the presence of intention and the outcomes of ordered dispersions of matter happening repeatedly, millions of times every year, in the form of the production of cars, beehives, microchips, airplanes, buildings, and a million more things. In each case, there is the presence of intention and actions directed towards the material components, which acquire 100% biases to be in exactly the required spaces and the required orientations to fall in place. There is a case to establish a definite causal connection between the intention and the results of ordered configurations of matter.

This correlation, or vyāpti in Indian logic, enables one to infer the presence of the ātman or a conscious entity (soul in the western parlance) from the presence of goal-oriented actions. Where there is an intentional action, there is always a conscious being present as the source. Whenever there is an absence of the ātman, the probability of spontaneous order from chaos approaches zero, as he shows in the book. He addresses the Darwinian arguments about evolution too. Yet, in contemporary discourse, intention does not have the pride of place of an ontological principle. It is simply a manifestation of some underlying physical state in the brain or body. The ‘explaining away’ is not through a logical elucidation but by asserting a dogma.

The dogma lulls the mind into thinking that the phenomenon cited for the inference of the self is a mere appearance. Thus, it is imperative to undertake a philosophical investigation of the belief that goal-oriented actions are nothing more than manifestations of underlying physical processes and show it to be a mere dogma. This refutation of the dogma forms the second part of his book.

Concluding Remarks

Brahman, or Self, with the primary attributes of Knowledge (sat), Truth (cit), and Bliss (ānaṅda) is the fundamental ground of both epistemology and ontology in Indian traditions. The ontology, or perception of reality, is an inside-out process starting from the Self which directly contacts the objects of perception. Knowledge of any object in the parā or aparā realm is an access to Brahman. Hence, any activity can be a route to mokṣa in Indian traditions.

Ananda Coomaraswamy and Śrī Aurobindo in the past and Śrī SN Balagangadhara in the present, people who have truly understood Indian culture, repeatedly stress that the concept of secularism, or the separation of the sacred and the secular, fails to make innate sense in our culture. There is absolutely no dichotomy when a rocket scientist breaks a coconut in the temple or when we invoke Sarasvatī or light lamps at the beginning of a conference discussing the highest principles of science.