Part 1

This article is Part 1 in a series summarizing the concepts expounded by Śrī Chittaranjan Naik in his piece, “The Realist View of Advaita.” The link to the original series has been provided and provides a comprehensive explanation of Advaita doctrines.

darshanas| advaita 27 March, 2025|4937 words

https://www.brhat.in/dhiti/realist-view-of-advaita-1

https://www.brhat.in/dhiti/realist-view-of-advaita-2

Introduction

Is the world real, a mental construct, or pictures of something else? Western philosophy and the sciences have broadly three positions on how we perceive reality.

- Representationalism (Scientific Realism or Indirect Realism) believes that the perceived world is only an internal representation of an external world; hence, it is an indirect form of reality. The brain reconstructs the neural impulses impinging on it to create a world outside. The real world remains unknown.

- Idealism believes that the world we perceive is subjective and has no existence independent of the mind. In both the above forms, the world is mind-dependent.

- Realism (or Naïve Realism) believes the world to be true to the representation in our brains despite paradoxically holding the stimulus-response theory of perception to be true. This view has the problem that, despite the transformative nature of perception, the world is still believed to be true to what it looks like. Hence, the term naïve is applied.

In the first two positions, if there is a mind-dependent world, then what is the ontological status or the true reality of the world? All representationalist systems cannot thus effectively address the topic of ontology (reality), as the real world is always beyond our comprehension.

The standard Western paradigm is that light falls on an object, reflected light enters through the eyes on the retina, neural impulses travel to the brain, an image is formed, and the perceiver ‘sees.’ The same is true for all the other senses, too. In the ‘stimulus-response theory of perception’, the perceived world becomes only a representation of the external world. In Kantian philosophy, the original unknown is the ‘noumenon’ (in modern parlance, ‘the non-linguistic’ world), and the known constructed reality is the ‘phenomenon’. Representation is the contemporary scientific view and gets the term ‘Scientific Realism’ or ‘Indirect Realism’, and forms the basis of both philosophy and neuroscience.

In contrast, the six systems of Indian philosophy have a clear stand of a ‘Natural Realism’ or ‘Direct Realism’. There is an active theory of perception where the perceiver, central in the scheme of things, goes out and reaches the object in the world. This is the ‘contact theory of perception’ of Indian philosophy. This gives direct information about the world as it exists, without any construction. Despite the pinnacle of philosophy being Advaita, there is plenty of misconception regarding the ontology of Advaita, especially when it says that jagat (world) is a mithyā (an illusion). What does this mean? Is it denying the reality of the world, equating it to the illusion of a magician?

The answer is a resounding negative. Śrī Chittaranjan Naik, engineer, scientist, eminent philosopher, and author of two books on Indian philosophy (‘Natural Realism and Contact Theory of Perception’ and ‘On the Existence of the Self’), explains the ontological view of Advaita in a brilliant series of articles published first at advaita.org.uk. Using the works of Śrī Adi Shankara, especially Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya, he discusses the realism of Advaita in great detail and shows how it does not stand in contradiction to the other schools of Indian darśanas.

Not only that, the series of articles dissects clean many of the key ideas of Advaita philosophy and the problems due to its incorrect interpretations, sometimes even by Advaita proponents. The series of essays is a must-read for understanding Advaita in a comprehensive manner.

This article and its sequel are a summary of the original series giving the main points of his article, which hopefully should be a stepping stone to explore the original essays and other works of Śrī Chittaranjan Naik. The author of this summary does not claim expertise in this area and only wants to continue Naik ji’s efforts to simplify some of the most complex Indian Darshana concepts, especially for the beginners and those who are completely unaware.

Unlike Western philosophy, which perhaps is of use to the philosophers strictly, Indian darśanas have a ‘utilitarian value’ for every single individual because the final goal of every darśana is the mokṣa of the individual. Thus, Indian philosophy has an intense practical benefit of transporting a person from bondage to complete freedom and from ignorance to wisdom.

The idea of excluding Indian darśanas in the name of secularism from Indian educational curricula by calling it “religion” has been the poorest understanding of Indian culture by our thinkers and leaders.

It has resulted in the great deracination and derooting of the Indians from their strong traditions. Perhaps it was a cultural and intellectual suicide for the country by ignoring Indian philosophies.

This article and its sequel conclude with a link to the original series, which includes an extensive bibliography for a deeper exploration.

The Reality Divide – A Historical Perspective

The ancients looked at reality as a natural world they saw, experienced, and lived in. A modern realist asserts that the world is independent of the perceiver, while an idealist reduces it to the mind. Contemporary cognitive science talks about two worlds: one, a qualia-filled consciousness of “subjective” world experience, and the other, the world of “objective” independent entities. In contrast, there is the more vexed duality, or reality divide, where most Advaitins term the experiential world an illusion or a dreamlike “product” of consciousness.

The nihilistic idealism of Buddhist philosophy first created the duality of the “outside world” and “inside world” only to negate the “outside world” as an impossibility. Logic dictates that when one pole of an artificially constructed duality collapses, the entire duality also collapses. Mimamsa philosophers dissolved this artificial duality and reverted to a logically meaningful world we see and experience.

In Western philosophy, John Locke formally divided the world of “secondary” qualities we perceive and the world of “primary” qualities forever beyond our senses. Bishop Berkeley, by demolishing the world of independently existing objects, helped establish the stage of idealism in Western philosophy. Idealism makes the outside world either a secondarily transformed representation in the mind or a sole play in the mind. Idealism remains an idea-tized island, sequestered from the imaged “outside world.” Modern philosophy across its history (British empiricism, German idealism, American pragmatism, and continental existentialism) and even contemporary science have not been able to revert to the only natural world that we experience and live in.

Edmund Husserl nearly succeeded in solving this riddle, but the scientific community found his phenomenological reduction too complex, arguing that philosophising about the “outside world” is futile. Wittgenstein, following Gottlieb Frege, came closest to resolving the reality divide by attempting to develop an ideal language to avoid the pitfalls of language misuse. Wittgenstein developed a full-bodied philosophy of language in which language and the world are intimately connected to each other. Few understood the ramifications of his philosophy. The reality divide continued to haunt philosophy.

Science borrowed many concepts from philosophy: the atomic theory (Epicureans); the belief in natural cause explanation for all phenomena (Lucretius and Bacon); space as a relation between mass points (Leibniz). Yet, science has never examined its own conceptions with philosophical clarity. The automatic approach is the positivism of August Comte, who posited three stages of development: the intuitive stage (religion), the speculative stage (philosophy), and the rational empirical stage (science). Many of its ideas regarding doing science, starting with the “verifiability” criteria, have repeatedly undergone changes. The reality divide remains an implicit premise.

Nyāya, the common platform for philosophical debate, a philosophy of logos, and intricately linked to language, never allowed this debate in Indian philosophy. Reality remains as the world that we see and experience. Yet, the idealism of Advaita gave a vision of the world as “illusion.” Ill-understood, this was the truth that the world is not independent of the perceiving consciousness. It is an epiphany, a point of spiralling into the numinous ground of Self. A real world does not mean that it is independent of consciousness. It merely means that we employ the natural locution that language has given us.

The “unreal” is known only by knowing the “real.” One is asleep to meanings until the Self, in which all meanings lie, is known. Advaita is a razor’s edge. The notion of truth and the discriminative capacity lie within us, by which we seek to know the world and understand the shruti. A philosopher must explain the world and not negate it. Sublation is seeing a new meaning in an experience, not negating it.

The Preamble to the Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya

The adhyāsa-bhāṣya of Shankara’s preamble to the Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya is popularly believed to point to the unreality of the world, but this is fallacious. The subject matter is the superimposition between the Self and non-Self. This superimposition is avidyā. Ascertaining the real entity by removing the superimposition is vidyā and finally facilitates Self-knowledge. There is no statement that implies the world is false.

One of the most famous illustrations in Indian darśanas that highlights superimposition is the “snake in the rope.” A dim light makes one think that a rope is a snake. The instant light falls, knowledge dawns, the snake vanishes, and the rope remains. Superimposition is the appearance of one thing as another, where an unreal thing appears as real. The object is unreal because the real thing does not exist at the place and time of its cognition. This is not a statement of absolute nonexistence. In the superimposition of the non-Self on the real Self, the non-Self is unreal, but it is never absolutely non-existent.

Shankara mentions the theories of error in other schools.

- Anyathākhyāti (Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika): The error from the rope is transported to a real snake that exists elsewhere due to either a defect of environment or instrument of cognition. Advaita rejects this because the perception of the erroneous snake should take us to the snake present elsewhere.

- Akhyāti (Mīmāṃsa): The error is transported to a defect in memory of the real snake. Advaita rejects this too since memory is never without a reference to place and time.

- Satkhyāti (Viśiṣṭādvaita): All objects of cognition are real since there is never a cognition without a real cognitum. Advaitins reject this theory because it does not explain why only a snake should be seen in the rope rather than a cow or an elephant (as everything exists in everything else).

- Sadasatkhyāti (Sāṃkhya-Yoga) is based on false knowledge not corresponding to its real form. The snake, real elsewhere, is unreal when comprehended in this rope. Advaita does not strictly reject this.

It is only in the nihilistic Buddhist theories that we come across the absolute unreality of even the objects of error. Asatkhyāti (Buddhist Madhyamikas) says that the non-existent snake appears on the non-existent rope. Advaita rejects it since the idea that “all effects are non-existent” goes against experience. Ātmakhyāti is the Buddhist Vijñānavāda theory of error where a past impression leads to a mixing up of a simultaneous flow of external ‘this’ and internal snake. Advaita rejects this, as Buddhists here are really assuming the existence of an external thing even while they deny it. The unreality of the “son of a barren woman,” an absolutely meaningless term, is different from the unreality of the “snake in the rope.” The world in Advaita is unreal, like the latter. Only the Buddhist doctrines say that the world is absolutely unreal.

An error occurs when there is a concealment of the true nature of the object, either due to a defect of the sense organs or the environment. Vaidika darśanas postulate two other conditions for error to occur:

- A likeness between the real and the unreal object. People mistake a rope for a snake, not a cow.

- The unreal object appearance is based on the reality of the object itself, though the locus differs. A rope can be mistaken for a snake because real snakes exist.

However, these conditional factors for empirical error are impossible to explain the non-Self being superimposed on the Self. One, insentient, and the other, sentient, are as contradictory as light and dark. This superimposition is hence inexplicable, but this is the natural (naisargika) state from a beginningless past.

What is unreal is also somehow and perplexingly the real. To read the bhāṣya of Shankara with the singular notion that the world is unreal would be a sad derailment of Advaita. How can superimposition happen on the Self, which is never an object? The Vedāntin response suggests that we apprehend the Self, which is not entirely beyond comprehension, as the content of the concept ‘I’. The Self is also well known as an immediately perceived (self-revealing) entity.

In the error of the snake in the rope, the person knows the meanings of both the snake and the rope. Children superimpose the ideas of concavity and dirt on space (the sky) while not knowing the true nature of the sky. An adult who knows what ‘sky’ means can never superimpose such ideas. There is a primal dislodgement of meaning in children. The superimposition of the non-Self on Self, inexplicable or anirvacanīya, is such a primal dislodgement of meaning in Reality.

The Dream Analogy: The Illusory World and Superimposition

According to Adi Shankara, the world cannot be said to be false based on the enigmatic dream analogy where perception occurs in the absence of external things. Shankara denies the appearance of objects without real ones existing for the following reasons:

- Waking state objects are never sublated, unlike those of the dream state. The latter state objects are sublated immediately on waking up.

- Dream vision is a kind of memory, whereas the waking state are perceptions of objects through valid means of knowledge.

- Objects cannot appear from mere internal impressions.

- Objects are not unreal because they have distinguishing characteristics.

A mere analogy of a dream cannot supersede what remains empirically valid. In the Brahma Sūtra Bāṣya, Shankara asserts that one cannot dismiss the waking experience as inherently baseless, as this would contradict the experience itself. People have mistakenly, and perhaps recklessly, used the dream analogy to “prove” that the world is unreal. Advaita holds that the world is unreal in a certain sense, yet it requires illumination and reconciliation through the discriminative knowledge of the real and the unreal.

What is Being Negated?

According to Shankara, the unreality of the world and world sublation have no meaning in isolation from knowledge of the Self. The subtle and perplexing negation in Advaita is that negating without a distinctive thing to negate becomes a duality. The solution to the riddle is in discriminating what Advaita negates. The denial is the surface of the world as constituting the depth of its true nature. There is nothing finally negated because the surface is ultimately subsumed in the Reality. The sublation of the world is nothing but the knowledge of the Self that subsumes the world.

The unreality of the world is not like ‘the son of a barren woman’, for such a thing is possible ‘neither through Māya nor in reality’. Māya can possibly only ‘give birth’ to what is already existent. If we read this in juxtaposition with Shankara’s words that the Self is ‘co-extensive with all that exists within and without…’, the meaning emerging is that the denial of the world is of the surface as constituting the true depth of its nature in which it abides in identity.

Negation is of a thing’s surface posturing as the deep Self. Knowledge and the truth of the world are its life, and the seemingly lifeless world is a superficial façade of its reality. Advaita negates this ‘corpse’ of the world. The three states of Jāgrata, Svapna, and Suṣupti are characterised by the sleep of death, while the Self remains eternally awake. And in that consciousness shines the real living world.

The Advaitic Superimposition

What is the Advaitic superimposition of the world on the Brahman like a snake on a rope? Imagine one becomes aware of a brown-surfaced object barely visible above the surface of water while sitting calmly by the side of a lake. The person initially misidentifies it as a log of wood, but a sudden splash reveals it to be a crocodile. The person superimposes the log on the crocodile object, but the features, such as the “coarse brown surface”, remain authentic. With the attributes remaining unchanged, the superimposed log immediately disappeared.

The crocodile is Brahman. The log is the superimposed world. The cause of the superimposition is the concealment of avidyā. The coarse brown surface represents features of the world, which is not false. The illusion is the false log that was ‘seen’.

The attributes responsible for the error cannot disappear with knowledge. Therefore, the assertion that the world is a superimposition on Brahman necessitates a thorough examination of the constituent elements. In perceiving the world, the attributes are not false, but the false is the world as a self-subsisting independent thing. The independent world is the ‘snake’ superimposed on Reality. Thus, negation does not negate the world in so far as the world is the attributive mode of Brahman but negates the world perceived as independently subsisting.

Kārikā on the Unreality of the World

Gaudapada’s Kārikā derives the unreality of the world from syllogistic inference (anumāna). In Vaidika philosophies, inference is not new, but prior knowledge, applied to the particular instance of observation. We can infer the fire from the smoke because of the a priori concomitance between smoke and fire. Vyāpti is an invariable concomitance between two perceived objects. The Vyāpti used in the Kārikā is meant to be understood differently.

If ‘being perceived’ is an object, the perceiver witnesses both the object and its apperception. Such is possible only for the Self that remains as the unmoving witness. The Kārikā speaks from a standpoint of this extra-normal perception where the unreality of the world is a prior truth. ‘Being perceived’ bears an invariable concomitance to ‘the unreality of what is perceived’ and becomes a vyāpti for the inference. However, this is only applicable to a jñāni or a yogi.

The Kārikā, much before Mīmāṃsa, takes a different perspective on the dream than does the Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya to refute Buddhist nihilism. In the tarka-śāstra, one way of refutation is to accept a common tenet of the opponent—called the siddhānta—and then demolish the conclusion. Shankara, in his bhāṣya to the Kārikā IV.27, after the illusoriness of the world has been established in the first ten verses of the Vaitathya Prakarana, moves on directly to a refutation of the Buddhists:

If the objects cognised in both the conditions (of dream and of waking) be illusory, who cognises all these (illusory objects), and who again imagines them? Atman, the self-luminous, through the power of his own Maya, alone is the cogniser of objects (so created). This is the decision of Vedānta.

Authenticity And the Knot of the Heart

Shankaracharya places great stress on authenticity, which is relevant to the understanding of Advaita. He says it is unacceptable that a person perceives an external object through sense contacts and still says that he does not perceive it and that the object does not exist. One should accept a thing as it is revealed externally and not ’as though appearing outside’. It cannot be asserted that the perception of the waking state is false merely on the ground that it is a perception like the perception in a dream. A strong stand of this type makes it unreasonable to assume that Shankara accepts the reality of the world merely for the sake of expediency when arguing with Buddhists.

Authenticity leads us to the truth of experience. Rejecting the world is but a twisted affirmation of the world. Rejection lays the groundwork for ‘reduction’, a process in which objects transform into nothingness, impressions, or quantum phenomena. Reduction is the perpetuation of the primordial confusion between ‘sameness’ and ‘difference’. The inviolable truth that “a thing is itself” is the central axiom of logic and the fundamental law of identity. Reduction, or viparyaya, contradicting the law of identity, is illogical since it mixes up the meaning of one with another. It is a corruption of the vritti whereby the object is not true to its name.

Shankara attacks this reduction when he refutes Buddhist doctrines holding that objects are internal impressions. An internal impression is not an external object. ‘Internal’ and ‘external’ are the attributions of space. Holding objects as only internal impressions is fallacious in ascribing reality to space but denying reality to objects in space. A cow is a cow and not a horse through its “cowness” more than because of any other reason.

Reduction roots in the unknowingness of the known-ness of objects. Things seen are already known. We cannot question what we don’t know. Yet, it is not known because we have questions about it. Thus, it is known, and it is not known. We cannot know it by rejecting it or bringing alien characteristics to it by way of reductions. The truth is seen through a transparent (and not warped) mind to the Witness of seeing. Reduction is a violation of the pramanas. According to the epistemological order of the pramanas, a fact of pratyaksha cannot be negated on the grounds of reason.

The law of identity directs the intellect to the Brahman. It fixes the universe ‘as it is’ in its true nature. Brahman, as the material cause, pervades the universe like the yarn pervades the cloth. Brahman is large enough to accommodate the universe as we see it. Brahman (roots: ‘brmh’ or growth with the suffix ‘man’) points to an absolute freedom from limitation.

Authenticity leads us to the infinity and not to the ‘nothingness’ of Brahman. The mind of a jīva is warped by avidyā that has ‘shrunk’ the self into the confines of the body. It is the knot of the heart that must be released. This knot has contracted the infinite into the finite. For a jīva to identify with Brahman, its consciousness must ‘expand’ to include all jīvas in the universe and the immortals of heaven. The Supreme Knowledge is the ‘expansion’ of consciousness to engulf the universe rather than its ‘compression’ into the nothingness of nihilism. The Self is All-knowing. How can one realise the Self that is All-knowing if the All has been negated?

Prelude to Ontology

Immanuel Kant questioned our use of the term ‘existence’ as a predicate. Gottlieb Frege, following Kant’s lead, formalised existence not as a predicate but as pointing to the instantiation of a concept in his symbolic framework, which later formed analytic philosophy and modern logic. Frege, countering the idealists, reasoned that ‘existence’ linguistically applies to objects as concrete facts. A variant of the ontology of presence is “existentialism”, where all things are nothing but their presence to consciousness. But the term ‘existence’ does not refer to consciousness itself. Existentialism further states that “existence precedes essence.” This doctrine dissolves everything into ‘a nothing’ behind the nature of things.

This hypothesis problematically cannot account for the recognition of sameness. No essence means no persistence in the idea of a tree being the same yesterday and today. The metaphysical need to account for sameness made the Scholastic philosophers postulate “essences”. Only by admitting universals or essences can we recognise sameness, but this negates the doctrine that ‘existence precedes essence’. Unfortunately, modern philosophy discounts scholastic philosophy.

However, Advaita affirms both the ontology of presence as well as the ontology of absence in an overarching ontology of Existence as we shall see later.

Object

The current usage of ‘object’ is something ‘concrete’ perceptible to the senses. The original meaning, more encompassing, makes no differentiation between an object both thought and perceived. The difference lies in the modes of cognition for the same object. When conceived, it is a concept, and when perceived, it is a percept. Joy, sorrow, motion, rest, doubt, and certitude are also objects. Modern philosophers have been perplexed by the padarthas of Nyāya, which includes such entities as object of cognition, instrument of cognition, discussion, etc. This is because they translate padartha as an ‘ontological category’. ‘Tattva’ and ‘padārtha’ have no exact English equivalent, but the closest could be the term ‘logos’.

An intermediate “sense” does not mediate the sacred and mystical relation between words and objects. An object is the immediate object of the word. It is therefore ‘artha’, which means both ‘meaning’ as well as ‘object’. According to Frege’s modern sense-reference theory, words possess an “intermediate sense” that refers to objects in the world. This is not logically sustainable. A word’s sense lacks meaning unless it encompasses the ‘objectness’. If the sense incorporates the objectness, it eliminates the need for a separate object as a reference. If it did, the object would have to contain something more than the objectness, and hence objectness would not define the object, which is absurd.

Mind and Object

Despite not having a separate thing called the mind, it has a sense of being internal and as the subject. It is thus an internal tattva — antaḥkaraṇa — that, apart from the objects cogitated, is inferred to be the internal instrument of cognition. The mind itself is an object because it is a reference to the word “mind”. This duality generates a kind of false duality. Things cogitated by the mind are ‘ideas’, and things perceived by bodies become ‘objects’.

There is no duality between mind and objects. The object is the target of the mind, and the mind, as the internal instrument, is the other side, like the concave and the convex. However, when we contemplate the mind itself, it functions as both an object and an internal instrument within our thinking. Modern philosophy cannot seem to bridge the seeming divide between mind and body, leading to problems such as ‘the ghost in the machine’ and the ‘hard problem of consciousness’. This roots in the stimulus-response theory of cognition, which divides reality into the ‘outside world of objects’ and ‘the internal world of sensations’.

Refutation of the Stimulus-Response Theory of Cognition

The stimulus-response theory of perception is a persistent dogma. Accordingly, the sensory signals that impinge upon the human sensorium, which is a tabula rasa, invoke it into a responsive state. This has remained unexamined except indirectly through Husserl’s phenomenology, which showed that we reach objects directly without mediation.

The brain-centric model postulates the brain as the cause of perception and ideation. A logical circularity ensues because the brain is also a perceived or ideated thing. Logic forces us to look at the idea that we reach objects directly without mediation. A valid theory of cognition must avoid the logical circularity of the stimulus-response model while accounting for the observed causal relationships. The refutation demonstrates that there is no transforming mechanism between the perceiver and the perceived world. Thus, there is the seer and the seen, and the seer sees the seen intimately and directly.

Thus, in the physical world, a Transcending Causality that orders phenomena manifests the brain as the seat of a certain causal nexus. The brain becomes a ‘cause’ of perception bestowed upon it by the Real Cause. The neural processes are more like a correlation to the world and not the cause.

The Individual and the World

There is thus one continuum of Consciousness in which mind, body, external objects, internal thoughts, and their causal relationships exist. The body, as the seat of our experience, is marked off from the rest of the world as ‘I am this’. The individual or jīvātman is a luminous clearing within the world circumscribed by the mind and body. Brahman creates the body as the abode of the jīvātman and bestows the causal nexus between the senses and the objects.

The jīvātman’s power affects the world only through the body. The jīvātman cannot determine the world into being. Even the dream-objects are brought forth by that same bestowing Cause. The jīvātman cannot create objects; it can only affect the objects that it already finds around it as the furniture of the world. The world, endowed with objects of sense perception prior to the individual’s determinations, is reached out to by the jīvātman with the body. Only the Transcendental Cause projects the world as a sensual manifold of objects by its vikṣepa śakti.

On Perception (Pratyakṣa)

If sensing is from outside to inside, we should see objects inside the body, not in space. To say that the object is perceived “as-if” it is there, is illogical since it lays the ground for anything to be anything else by effacing all differences. The only logically sustainable thesis is that objects are perceived through contact between the instruments of cognition and the object. This is the Advaita theory of perception. The mind and the senses reach out, contact the object, and comprehension takes place in the intelligent light of consciousness. We perceive an object as it is, without any transformation. An inconceivable ‘outside world’ collapses. Advaitic metaphysics dissolves the schism between mind and body and between primary and secondary qualities.

PART 2

Ontology

Dravya (Substance) as The Ground of Being

The important points are:

- Substance, revealed in the perception of an object as the existing thing, is never experienced by itself. Immanent as the ground in the things experienced, it is the existential core of the thing and the object’s substantiality. A dream horse is insubstantial, but the reality immanent in the perception of a real-world horse is the existentiality of substance.

- Substance is also a unity of all sensual and non-sensual predicates that characterise a thing. We perceive objects as possessing sensual attributes. We do not see complex colours and shapes floating; rather, we see apples, tables, and so on with these qualities. The perception of a tree is immediate and not an experience of agglomeration of sensations bundled into a unity, as some empiricists say. This is an inference that supersedes an empirical fact.

- All the attributes are coterminous with the substance. Śrī Ādi Śaṅkarācārya (Śaṅkara) refutes the duality of substance and attributes by refuting the relationship of inherence which leads to an infinite regress. Substance is the existent, and attributes are its descriptions. It is this truth embedded in language wherein identity is predicated between the substance and attribute by a subject-predicate form: ‘An apple is red’.

- Substance, bare and abstracted from attributes, is indiscernible and noumenal. Every manifestation has an existential core, even the form given by the name “mirage” or “dream horse.” All these are in the noumenal ground of Existence, One and not many, because substance, qua substance, is bare and indiscernible. There cannot be a difference between indiscernible ‘things’, because difference is nothing but a discernible. Therefore, substance, divested of attributes, is One and indivisible.

Thus, there is nothing that is non-existent, but only Existence manifesting non-existence as a manifestation of its attributions. Experientially, things may or may not exist, but at a deeper level, they are all unreal, belonging to the chimaera of substantiality bestowed by names and forms. And yet, at the deepest level, they are ultimately all real, with their existential core being the noumenal ground of Existence. There is nothing but Existence, even in the unreal, it being only a mode of the Real.

Vivartavāda and Ontology

The world is unreal because it exists in the middle but not in the beginning and the end. When things exist in the middle, it means –

a) either that they are non-existent (because of their absence both yesterday and tomorrow), or

b) it was always there and that its coming into existence is merely a false seeming. Advaita, adhering to its tenet of satkāryavāda, affirms the second and rejects the first position.

The fundamental ground of logic in understanding creation, destruction, and change is that a thing is identical to itself. There is an unchanging principle or ‘being’ of the object which stays the same despite changing attributes. This ‘being of the object’ is substance, as we have seen. As an example, a hypothetical circular coin made of wax can be changed to a square form. Different attributes, each of which is unchanging (the square is not a circle), were displayed in the ‘change’ attributed to the object.

The law of identity is not violated, and yet change is possible as the showing forth of attributes that are pre-existent in the substantial ground. Change is the manifesting dynamism of things that are each unchanging. This dynamism is real and is called ‘Time’ (Kāla). In truth, there is nothing born, nothing destroyed; everything is eternal in the infinite nature of Brahman.

Śaṅkara argues that the effect already exists prior to its production. Manifestation means a pre-existence that comes within a range of perception, like a jar hidden by darkness, which becomes perceptible with the falling of light. Even when the sun rises, we cannot perceive a non-existent jar. Every effect has two kinds of obstructions. A jar after manifestation from its components has darkness and walls as obstructions to perception. However, before manifestation from the clay, the obstruction consists of particles of clay remaining as some other effect, such as a lump.

‘Destroyed’, ‘produced’, ‘existence’ and ‘non-existence’ depend on this two-fold character of manifestation and disappearance. Śaṅkara finally concludes that separable or inseparable connection is possible between two positive entities only, not between an entity and a nonentity, nor between two nonentities.

The Real and Unreal in Advaita

The absolutely unreal is “the son of a barren woman” — a meaningless term. The real, all that is seen and conceived, is the opposite of the unreal and hence, all that has meaning. The second meaning of unreal is adhyāsa, the mistaking of one thing for another. Our way of cognition through both the senses and mind is responsible for this superimposition.

Substance is the ‘thing’ perceived, and the attributes are perceived as being ‘of the thing’ perceived. The senses grasp the attributes, but the mind grasps the thing where the attributes inhere. Adhyasa takes place when the attributes are seen, but the substance or the ‘thing’ is falsely believed to be something else by the mind.

Vyāvaharika is the state when the sentient Substance (Brahman) of the world is concealed and the mind rushes out to grasp the insentient prakṛti (nature) as the substance. This ‘world’ superimposed on Brahman is false. Adhyāsa is a natural feature of the people in this world. The world in the continuum of Brahman is, however, the reality of Advaita, in which there can be no superimposition.

Advaita

Difference

If the universe of names and forms is real, then why is Brahman described as formless and nameless? The issue of distinction represents the ultimate frontier of philosophy, defining the boundaries of logic and language. Brahman, like the yarn in the cloth, is the material cause of the universe. Then how indeed does the cloth become false when the yarn is true? A mere assertion that whatever pertains to names and forms is false would amount to a dogma, and this negation would make Advaita nihilistic.

Whether the difference is in material cause or attribute distinctiveness, it is not logical. Therefore, difference is an admixture of truth and falsity. It is not possible to speak of the true nature of that which partakes of falsity — ‘anirvacanīya’. The confusion between ‘sameness’ and ‘difference’ is the primordial confusion since a beginningless past. We must now approach difference from another direction.

Words and Denotation

Advaita says that a word does not point to the particular but only to the universal. Even when an object ‘changes’, its name remains the same. The Nayyāyikas (Logicians), the Vayyākaraṇas (Grammarians), and those from other schools of Vedānta hold that words point to both the universal and the particular. Advaita refutes this by saying that if this were the case, then it would occasion a new name every time a different attribute is seen, as the combination of universal and particular (U+P) would be a new combination. An infinite number of names for the object makes it unreasonable.

Gautama (the founder of Nyāya) objects and says that this is not right because the manifestation of a universal depends on individuality and configuration. The Advaita response is that there is no difference between the sāmānya (universal) and viśeṣa (particular). If disparate and non-conjunct, then a viśeṣa could never belong to a species. Again, according to the Śruti, the truth is revealed when we withdraw from the world of sense objects. Śruti would not be misleading here in its objective. Then, how is it that by knowing the Self, everything comes to be known?

Sāmānya (Universal) and Viśeṣa (Particular)

Words denote only universals; the latter are objects themselves; otherwise, words cannot point to objects. Universals necessarily exist, and without them, there cannot be recognition. For cognition of ‘this’ (a cow, for example), it requires a recognition of a universal ‘thisness’ (cowness). A universal is unthinkable because the very act of thinking particularises it. Failure to see universals as unthinkable and that thinking is always particularised has caused much befuddlement in modern philosophy.

A universal, formless, and non- spatio-temporal entity is yet the essence of form. There are no unspecified particulars into which universals enter or ‘participate’. The term ‘participate’ is metaphorical. There can be nothing except amorphousness without universals. A universal makes a thing what it is. It is not possible for the particular to be more than the universal. Thus, so far as the universal to become a particular is concerned, there is no difference between the universal and the particular. But the other way around — a particular is not the universal itself. It is possible for a particular cow to be absent from another instance where the universal is present, i.e., in another cow. Thus, universals are present wherever there is a particular, but the reverse is not true. However, a particular is wholly nothing but a universal, albeit a partial vision.

The universal is the complete infinitude of attributes of the thing, of say ‘cow’, and it pervades all particulars. A universal can manifest simultaneously in all instances of its particulars because it has no form and is not spatio-temporal. Words denote universals. Therefore, the world of forms that is denoted by names is the “sameness” of universals. The latter is the formless whole of all its particulars — the very knowledge of things in the omniscience of Brahman. The formless Brahman therefore contains the infinitude of all that was, is, and will be. It is the intelligence that carries infinite universals in Its ineffable formlessness and undisturbed sameness.

Avacchedavāda

The world of sense is the world of ‘concrete’ particulars, of the limitedness of the unlimited. This is avacchedavāda, the doctrine of the falseness of the seeming limitedness of the unlimited. Therefore, the negation that the entire world is false is a negation of the limited as the true form of the unlimited. This is ābhāsavāda, and yet, in a perfectly logical manner, there is nothing excluded from Reality in the negation. Reality is full (pūrṇam).

In the Bhāṣya to the Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣad, Śaṅkara elucidates the four quarters, or pādas, that Brahman possesses.The first three – Viśva, Taijasa and Prājña – are successively merged into the fourth, or Turīya. Thus, the elimination of both name and form, that is different than Brahman, is the limitedness of the names and forms of the world of sense; and what is attained is the unlimited world, in which all the previous three gain identity. The smaller units lose their individuality in the bigger ones. Hence, Viśva merges in Taijasa, Taijasa in Prājña, and Prājña in Turīya.

Brahman, being different from both name and form, is its transcendence from them. The word ‘transcend’ does not mean a spatial or temporal separation but a distinction of the subsuming principle. A metaphor might be Einsteinian physics subsuming Newtonian physics without rejecting it. There is nothing negated here — a blade of grass, a speck of light, a mite in the moonbeam, a thought. The nirguna Brahman is also gunapoorna.

The Mystical Reality

Reality is mystical, where the magic of words plays upon non-duality and binds us to plurality. A word is essentially one with Brahman as parā vāk. It gives rise to the paśyantī — the causal seed. In its middling state, madhyamā presents the forms in ideality. Finally, the created world manifests as vaikharī. The mystery is that the word points to the same object in all its stages. Difference arises through Vāk. It is the heart of the mystical (Māyā), the inexplicable power of the Lord to make many out of One while still remaining immutably One. The eye of a mystic in Sahaja samādhi sees the One in All and the All in One.

Īśvara

The Origin

Who is there who truly knows, and who can say,

Whence this unfathomed world, and from what cause?

Nay, even the gods were not!

Who, then, can know?

The source from which this universe hath sprung,

that source and that alone, which bears it up – none else:

THAT, THAT alone, Lord of the worlds,

in its own self-contained, immaculate,As are the heavens above,

THAT alone knows The truth of what Itself hath made – none else!The Ṛg-Veda Hymn of Creation

The Śruti attributes the origin of the universe to Īśvara. Śaṅkara explains in Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya:

Brahman is the yoni… It goes without saying that that great Being has absolute omniscience and omnipotence, since from Him emerge the Ṛg-Veda, etc. – divided into many branches and constituting the source of classification into gods, animals, men, castes, stages of life, etc., and the source of all kinds of knowledge… Those that are called the Rg-Veda, are but the exhalation of this great Being.

On The Meaningful Use Of Words

Entropy postulates a tendency to chaos and disorder in the universe. The probability of parts of a clock spontaneously arranging themselves is near zero. Yet, entropy is continuously violated, astonishingly unnoticed, in the form of endless ordered structures (beehives, gathering of honey, anthills, seeds growing into trees, car productions, microchip productions, aeroplanes flying). The loci of these tendencies to order are living beings. Life, or intelligence, brings order to the chaotic inanimate matter.

Discussions on efficient causality have often been obscured by improper language use. Omniscience is understood as a manifestation of avidyā. This is unreasonable. Beauty is not a manifestation of ugliness. Words must be employed in consideration of their meanings, or there would be universal confusion. By definition, avidyā is lack of knowledge. Driving and cooking, when undertaken with knowledge, lead to the intended goals. Intelligent, goal-orientated actions are disruptive of the closed systems within which the principle of entropy operates.

A rare spontaneous assembling of one clock from its parts might happen, but a repeated assembly would need an extraneous factor, the directedness of intelligence. Only vidyā with these connotations — intelligence, design, and goal-orientation — can bring about order and regularity. Avidyā, with neither intelligence nor directedness, may contribute only to chaos. Therefore, it is intelligence rather than avidyā that is the efficient cause of the universe. We should understand Māyā as the power that Brahman uses to create this universe. Māyā is not avidyā.

Īśvara, Māyā, and Avidyā

The confusion between avidyā and Māyā arises from a misinterpretation of the Bhāṣya, wherein it is stated that the omniscience (all-knowing) and omnipotence (unlimited power) of God are contingent upon the nescience of the jīva. The word ‘contingent’ here implies a condition upon which something else happens. Avidyā is the condition, and what happens is the response of Reality to that condition. The response springs from its innate power, given the contingency of avidyā and the accumulation of karma caused by it.

Avidyā is not the cause but is the contingent factor, like the wall of obstacles breaking to let waters flow, upon which the very nature of Brahman ‘acts’. Because Brahman acts by nature, He lacks agency in His actions, as they stem from His own immovable nature. Māyā is Īśvara’s incomprehensible power of creation in response to avidyā. The bringing forth is done by a power of projection, or vikṣepa śakti. Particularisation hides the infinitude of the universal. This is āvaraṇa (hiding) śakti.

The knowing eye (the third eye) knows the infinity even in the particular. Avidyā takes the finite for the infinite. Īśvara has no avidyā. Vikṣepa and Āvaraṇa are the capacities of his infinite power — the power of Māyā. Existence and the magical power of Existence are not two. They are Īśvara and His Māyā; Śiva and Śakti; or Puruṣa and Prakṛti.

A yogi, through the eight siddhis, attains a fractional power. However, the power of creation remains with Īśvara alone. The weft and weave of the cloth cannot negate it. How can the jīvas with their minds, identified with so many sheaths of Reality, deny the world when it cannot see the wellsprings of the world, the Brahman holding it aloft?

Summarizing: Reconciliation and Non-Contradiction

Samanvaya (Reconciliation)

Advaita is absolute non-duality, and our interpretation should not make it a disguised duality. We must seamlessly reconcile the two statements that represent the final vision of Advaita:

- Brahman alone is real; all else is unreal.

- Brahman is That by knowing which all this is known.

How can we achieve samanvaya (reconciliation) and not virodha (contradiction) between them?

The dialectic, which does not deny the ALL, but denies the condition in which the ALL appears to be ELSE, provides the answer. For the ALL to be ELSE, it must stand in OTHERNESS from Brahman. The core of the negation lies in this otherness from Brahman. There is only Brahman and nothing else, and still there is no-thing that is actually denied, because the All that is denied as standing in otherness from Brahman is subsumed in the Oneness of Brahman.

Śaṅkara says in the commentary of the Chāndogya Upaniṣad: words and all things that are spoken of with THE IDEA OF THEIR BEING DIFFERENT FROM EXISTENCE are Existence only. Śaṅkara equates the false idea “that it is a snake” to the false idea “of the world being different from Existence”. The universe as Brahman is real; the idea that the universe stands independent of Brahman and is self-subsisting is unreal.

The Dialectic Of Material Causality

The locution where the unreality of the world arises cannot be considered in isolation from the Advaitika dialectic. For example, guṇa (attribute) is separate from dravya (substance) only through falsity and arises only through articulation of speech. Logically inexplicable, speech allows the false to be spoken. It is anirvacanīya because it arises through the self-referencing nature of Māyā. Neurosis of saṃsāra is the schism of being separate from the Self when in truth there is no separation. TThis explains why some schools refer to realization as ‘union’, while others refer to it as ‘healing’.

Advaitika dialectic both affirms and negates the world. The effect (the world) is not different from the cause (Brahman). The seeming separateness has ‘vācārambhaṇam’ – speech for its origin. The truth is the identity of the effect with the cause, and the falsity is their separateness. The falseness is ‘vikaraḥ’, transformation, that is ‘nāmadheyam’, having its origin in name only. The effect, always pre-existent in the cause, undergoes no real transformation. It is the mystery of speech that generates the illusion of a changing generative world. Therefore, ‘jaganmithyā’ relates to the speech-generated pole of falsity. But the pole of truth is that the world, non-different from Brahman, is real only. It is due to this non-difference that the All is known when Brahman is known.

The Mystery of Vāk

Most (contemporary) interpretations ignore Advaita’s philosophy of language to understand its dialectic. Śaṅkara mentions three important tenets:

- A word is eternal and is eternally connected to its object.

- A word denotes the sāmānya and not the viśeṣa.

- A particular (viśeṣa) is non-different from the universal (sāmānya).

These three in combination conclude that the difference of the effect from the cause arises due to the mystical difference in the conditions of speech. The evolution of names and forms (vivarta) is what the Vākyakāras call the staging of speech. The stages are parā-vāk, pashyantī-vāk, madhyamā-vāk, and vaikharī-vāk. They are the different stages of speech, and yet in each stage, the word and object of the word remain the same. A form is not a non-form because it is unmanifest. In the unmanifest state too, it is the same form that is manifest.

Difference is seen in the world of particulars. But a particular is the universal instantiated as a particular. The sāmānya is the fullness of the viśeṣa. Therefore, avidyā, the lack of knowledge, is the showing forth of the limitedness of the unlimited. This is Avacchedavāda (Bhāmati School of Advaita). Abhinavagupta, the great exponent of Advaita -Tantra in Kashmir Shaivism, uses the term ‘apūrṇakhyāti’ to express the same idea.

Vivartavāda and Non-Creation

Creation proceeds out of the ‘evolution’ (vivarta) of names and forms. ‘Creation’ is only the pre-existent in Brahman. Therefore, there is in truth no creation. What is always already born cannot be born again. This is Vivartavāda — the doctrine of non-creation. Only when we habitually attribute existence to an object’s mere manifestation does it become transitory. In truth the existence of an object is eternal, and the predications of ‘existence’ and ‘non-existence’ point to the world of vyavahāra. False is the transitory nature of things rather than the things themselves.

The real persists in all the past, present and future eternally. The individual jīva in the world of ordinary affairs, however, does not perceive the world like this. As a concession to common sense, the universe is said to be non-existent before being evolved through name and form. The “no non-existence of anything anywhere” and “all is Brahman” are the unbroken visions of paramarthika-satya that are true for a Jñāni. Time (Māyā) is the agent that imbues objects with its own attribute of change. The Jñāni sees truly that nothing is born, and nothing dies.

The Nature of Brahman as Nirguṇa

Brahman is the formless Pure Knowledge. A form is not of its Knower, but the form that the Knower knows. The object of knowledge is not descriptive of knowledge itself. Brahman does not have the svarūpa (form) or guṇa (attribute) of anything It knows. Brahman is nirguṇa. Brahman is Pure Knowledge in which all forms are eternally present. Therefore the highest truth is that Brahman is nirguṇa, which is also purṇa (full) with knowledge. That is His omniscience. Nirguṇa Brahman is the sole reality. The All does not contradict the perfect formlessness, the perfect immutability, the perfect Oneness, and the sole reality of Brahman. This Brahman of the Vedas has to be known through the Divine Third Eye, or the Eye of Śiva. He who opens it is Śiva.

Avidyā and Adhyāsa

The unmanifest avidyā, or a lack of knowledge, and the manifest adhyāsa are two facets of the same non-thing. Adhyāsa is the superimposition that is contingent upon avidyā. Āvidyā is the unmanifest root from which false bhavas rise as many branches. The most primary is that all this is ‘other’ than Brahman. The ‘otherness’ of the world is superimposition, or adhyāsa. The avidyā known as mula-avidyā refers to concealment or lack of knowledge, while the bhava-rupas of avidyā are false notions. The latter is adhyāsa.

The object is known because we see it. Yet the object is not known because we have questions about it. This characteristic of worldly people generates questions and the sciences. But scientific explanations are untrue if they do not conform to the intrinsic natures of things. Any explanation that fixates us in the artefacts of our explanations as being the truth is false. When Advaita says that avidyā colours the world, it is not saying that the world itself is false. The eye of knowledge opens to see that the world is Brahman. The closure of the third eye is the sleep of saṃsāra.

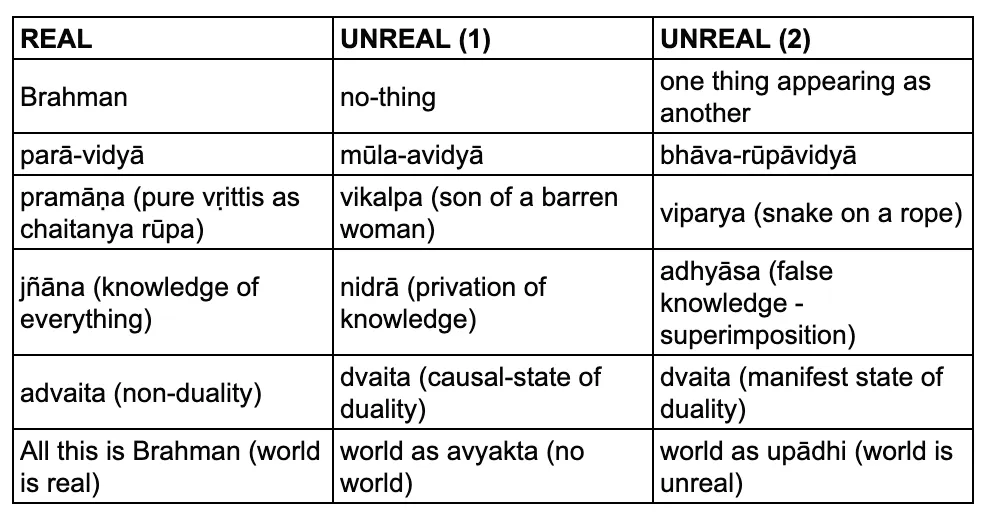

The Real and The Unreal

The unreal is meaningless and cannot be pointed out like ‘the son of a barren woman.’ In Advaita, everything that has a name is real. There is a second type of ‘unreality’ characterised by loss of genuineness.It is a kind of sleep, the causal state of ‘privation of knowledge’, which carries the potency for superimposing false notions to things. It is this second meaning of the word ‘unreal’ that we find in the context of adhyāsa. The chart below makes it clearer.

In recent years, there has been an attempt to ‘show’ that bhāva-rūpa-avidyā is an aberration of Śāṅkara Advaita. The main worry is that allowing bhāva-rūpa-avidyā would mean allowing a “real” avidyā, and that a “real” avidyā would make moksha impossible and make the Advaita position impossible to defend.

Such an apprehension is ill-founded. Mūla-avidyā and bhāva-rūpa-avidyā are nothing but suṣupti and adhyāsa. While the attempt to purify Śāṅkara Advaita is commendable, the cleansing process unfortunately discards a significant portion of Śāṅkara Bhāṣya. Bhāva-rūpa-avidyā does not make Advaita vulnerable to the attacks of the Pūrvapakṣa because its very manifestation is parasitic upon Mūla-avidyā, which is no-thing.

In the vision of Truth, there is no privation of knowledge (avidyā), and hence there is no scope for superimposition. The pūrvapakṣa loses the weapon of a ‘real’ avidyā with which to attack Advaita because the causal state of avidyā is no-thing and bhāva-rūpa-avidyā too is not a thing but a wrinkle that cannot exist without this no-thing.

Avirodha (Non-Contradiction)

The Māyā Vada is a main objection against Advaita based on the premise that Advaita equates adhyāsa with the world. This objection collapses when it is seen that Advaita’s world is real and that world-unreality is only the superimposition of Brahman’s otherness.

Again, the allegation that Advaita injects an extra-Vaidika notion of superimposition or adhyāsa into the Vedānta sutras has no base. This is because adhyāsa is nothing but the no-thing of avidyā. An avidyā that is not equated to the world is common to all Vedantika schools. Therefore, the argument that Advaita is non-Vaidika in character is groundless. When the confusion regarding ‘Māyā vāda’ clears up, what remains are the real differences between Advaita and other schools of Vedānta. These differences ultimately reduce to the difference of ‘difference’. Any difference between the world and its substratum is not sustainable and is false. The pratibimba (reflection) is always one with the bimba (object being reflected).

The samanvaya of Advaita is a perfect and immaculate non-duality of Brahman without necessitating anything being euphemistically called non-existent. There is no contradiction between statements of jaganmithyā and statements about the world being real because the former speaks about the falseness of adhyāsa and the latter about the truth of the identity of the world with Brahman. Again, there is no contradiction between the Advaita position that the world is “mithyā” (illusory) and the Advaita argument against the Buddhists that the world is real.

Advaita says that Brahman is the Self of the world. It is the sat (existence) giving to the world its reality. The Buddhists denying a substratum to the world regard the latter as a void, like the illusion of a firebrand. Śaṅkara argues that the world is not void but has a real substratum (Self) and is therefore not unreal. Regarding the argument for jaganamithyā, Śaṅkara says that the jīva, characterised by avidyā, affirms the world but sees the world bereft of its Self. Such a world (that is bereft of the Self) is unreal, and hence arises the expression of ‘jaganmithyā’.

Samanvaya, or reconciliation, is that each of the above two is made conditional to a stated position. But unconditionally, the world is real because it has Brahman as its substratum. To an opponent’s doubt that the Self might be a product of something else, Śaṅkara explains in his Brahma Sutra Bhāṣyam:

Now, if even the Self be a product, then since nothing higher than the Self is heard of, all the products counting from space will be without a Self, just because the Self is itself a product. And this will give rise to nihilism.

Brahman and The World

In Viśiṣṭādvaita, the relationship between Brahman and the world is that of substance-attribute, and hence the world is the body of Brahman. In Dvaita, the relationship between Brahman and the world is that of independent-dependent existences. Brahman is the independently existing Bestower of dependent existence in the world. Another school of Vedānta expresses the relationship as acintya-bhedābheda (unthinkable-identity-and-difference).

Advaita does not subscribe to any of these doctrines. The world is one with Brahman, and no relationship can describe it. Śaṅkara says:

Brahman’s relationship with anything cannot be grasped, It being outside the range of sense perception.

The mind cannot grasp the relationship between Brahman and the world, as it is not a relation. Nothing can fully express this wonder because it is already the relation-less unity in the expression of the world. This mystical nature is neither opposed to reason nor is it fully expressible by reason.

Concluding Remarks

Śrī Aurobindo, one of the most ignored intellectuals of modern India, and who arguably had the best grip on Indian culture, its traditions, and its philosophies, wrote in ‘The Life Divine’ –

The two are one: Spirit is the soul and reality of that which we sense as Matter; Matter is a form and body of that which we realise as Spirit… Matter also is Brahman and it is nothing other than or different from Brahman.

Advaita is indeed a razor’s edge. One may believe they have grasped the philosophy, but it can quickly elude them. As a metaphor (not to be taken too strictly), Advaita is to Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika what quantum physics is to Newtonian physics. In the solid world in front of us, it is Newtonian physics that rules, just as Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika explains the world around us. Nyāya is the basis of all our knowledge-seeking, debates, reasoning, logical systems, dharmaśāstras (the guides to living a proper life), and upavedas (the branches that discuss arts, music, sciences, engineering, and architecture).

Quantum mechanics gives a higher-order explanation of the world but without rejecting Newton. It subsumes the latter into a larger framework where the subsumed is not false. Advaita’s relation to Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika is something similar. The former subsumes the latter into a larger framework. Though both quantum physics and Advaita have a grander scale of explanatory power, it is also true that both are not understood properly even by their proponents fully. Feynman famously said, “I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.” Anyway, Advaita is the pinnacle of Indian philosophical systems, which have been enthusiastically taken up by people across India and the world, especially the new-age gurus, and yet it has been consistently misinterpreted.

As Śrī Chittaranjan Naik jī rues, the multiplicity of Advaitika traditions and their consistent disagreements on the interpretation of Śaṅkarācārya’s writings have abetted the confusion regarding some of its important ideas. In Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, the perceiver (Ātman) and the perceived (world) exist as real entities. The point that Naik jī makes in the article is that, for Advaita, the world exists as a superimposition on the real Brahman. Brahman is ‘all’, and in this all, the world is also real. To say that the world is either completely non-existent or exists as an independent entity without a substratum is a falsity. It is this falsity which Advaita rejects.

Anyway, spiritual giants like Ramana Maharṣi or Śrī Aurobindo always insisted that reason and intellect are limited faculties when trying to gain Advaitika insights. Are the gods real? Ramana Maharṣi says in one of his talks that a vision of God is only a vision of Self objectified as the God of a particular faith. The Vedantika vision of Advaita does not dissolve the world of men or divine beings into nothing. It goes into the essence of all the experience and perceptions to realise that everything is Brahman only. Śrī Ramakrishna once said that an Advaitika seeker discovers first that the world is unreal and then later sees it as real. The real and yet unreal world is indeed perplexing.

In the Advaitika vision, the world never disappears. Ādi Śaṅkarācārya explains in his Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya that the world is not annihilated like ghee with fire. The annihilation of the existing universe of manifestation is an impossible task for any man, and hence the instruction about its extirpation is meaningless. Even if it were possible, the first man to achieve liberation would have annihilated the universe. The first liberated person would have ensured that the present universe was devoid of any manifestation.

Hence, the realism of the world and its attributes is very much intact in Advaita. The negation is of the idea that the attributes of the world have an independent existence without a substratum of Brahman or the Self. As Śrī Chittaranjan Naik explains in his first book, ‘Natural Realism’, the oft-repeated criticism that Advaita’s position is that ‘nothing is real’ is a profound misunderstanding. The complete expression is brahma-satya, jagan-mithyā. The subject matter of Advaita is Brahman and not the world, and thus, jagan-mithyā is never an isolated proposition. The locution of jagan-mithyā (world illusion) is always with the locution of Brahma-satya (Brahman Reality).

A discussion of the world, excluding Brahman, however, makes it satya, or real. Denying the reality of the world, which excludes Brahman, reduces it to an unacceptable nihilism. Ādi Śaṅkarācārya takes the position that the world is real, refuting Vijñānavāda and other idealist schools of Buddhism that deny Brahman. Modern proponents of Advaita Vedānta overlook this vital point.

Naik jī further explains that the relation between Brahman and the world is the relation of Bimba-Pratibimba, the object and its reflection. There is a common misconception arising about the ontological (reality) status of the reflection seen in the mirror. The reflection, say of a flower, is unreal, but the object called ‘image of a flower’ is real. In other words, the object is not true to the name ‘flower’, but it is true to the name ‘image of a flower’. Each object in this world may be a reflection (pratibimbas) of Brahman, but they are true to their names. Hence, they are real. Their existences are entirely dependent on the Bimba, which is Brahman, the Supreme and Sole Independent Existence.

However, this vision is available to the highest of seekers. For the teeming ordinary mass of people, reason and intellect can only reach a certain height. The leap to the highest insights can only happen in the deepest contemplation when the mind dissolves and only the Witness remains and the insight happens intuitively that all is Brahman. The world, being nothing but Brahman, however, remains intact.

The original article series upon which this two-part summary series is based, can be found here.