This is a wonderful article written by Rohit Shinde on his substack platform and needs to read carefully. Link to the original article provided below.

A look into the patterns driving hostility against Indians.

Nov 03, 2025

Last week, I conjectured what would happen if, hypothetically, all Indians holding H-1B visas in the US were asked to leave. I dwelled on two case studies where Indians had been outright expelled: Uganda and Myanmar. But there have been many countries where Indians have faced protests and even outright resentment from the majorities of the countries they reside in. In this post, I want to explore what countries is it most prevalent in, and why it happens.

Thanks for reading The Indic Prism! This post is public so feel free to share it.

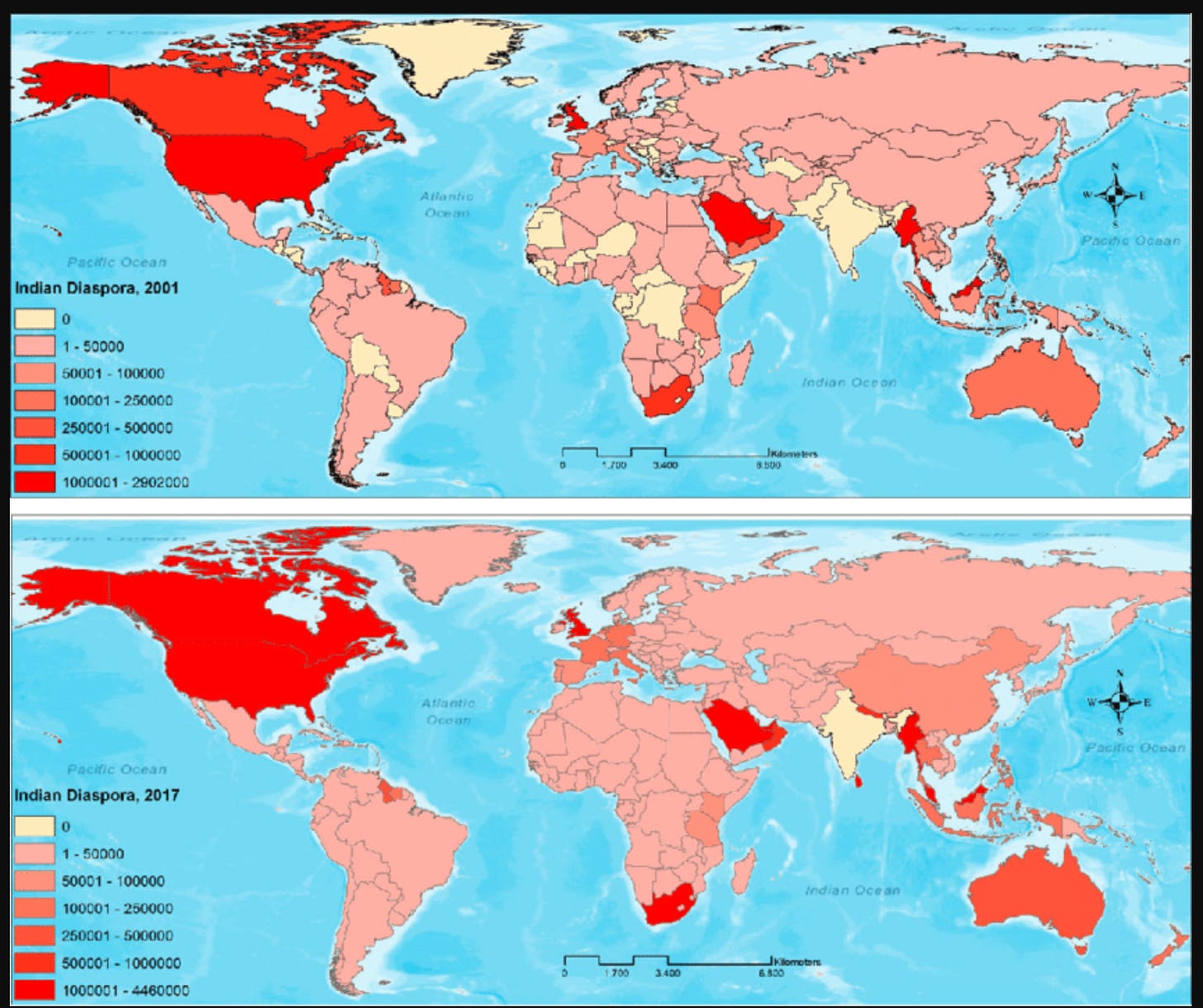

Let’s start off with some interesting facts about the Indian diaspora. All of these are taken from the Ministry of External Affairs data. When I refer to Indians, I will refer to both, Non-Resident Indians (NRI) and Persons of Indian Origin (PIO) together.

- There is no country in the world which doesn’t have Indian diaspora. If there’s a flag and an airport, there’s probably an Indian there too!

- North Korea has 16 Indians at present. Why? I have no idea. Similarly, even microstates like St. Kitts and Nevis have a few hundred Indians living there. In South America, Chile and Argentina both, have a few thousand Indians living there.

- Approximately 30 countries have someone of Indian origin as an elected representative. This includes obvious countries like the US and the UK. But even countries like Argentina1 and Zimbabwe2, both of which have 1 elected person of Indian origin.

- The diaspora — including both PIOs and NRIs — is 35 million strong. Counting only NRIs, there are about 17 million.

- One thing that puzzles me though is that there are about 1 million PIOs in Kuwait and about 2 million in Saudi Arabia. I have no idea why. Especially since I was under the assumption that citizenship is Arab countries is quite restrictive.

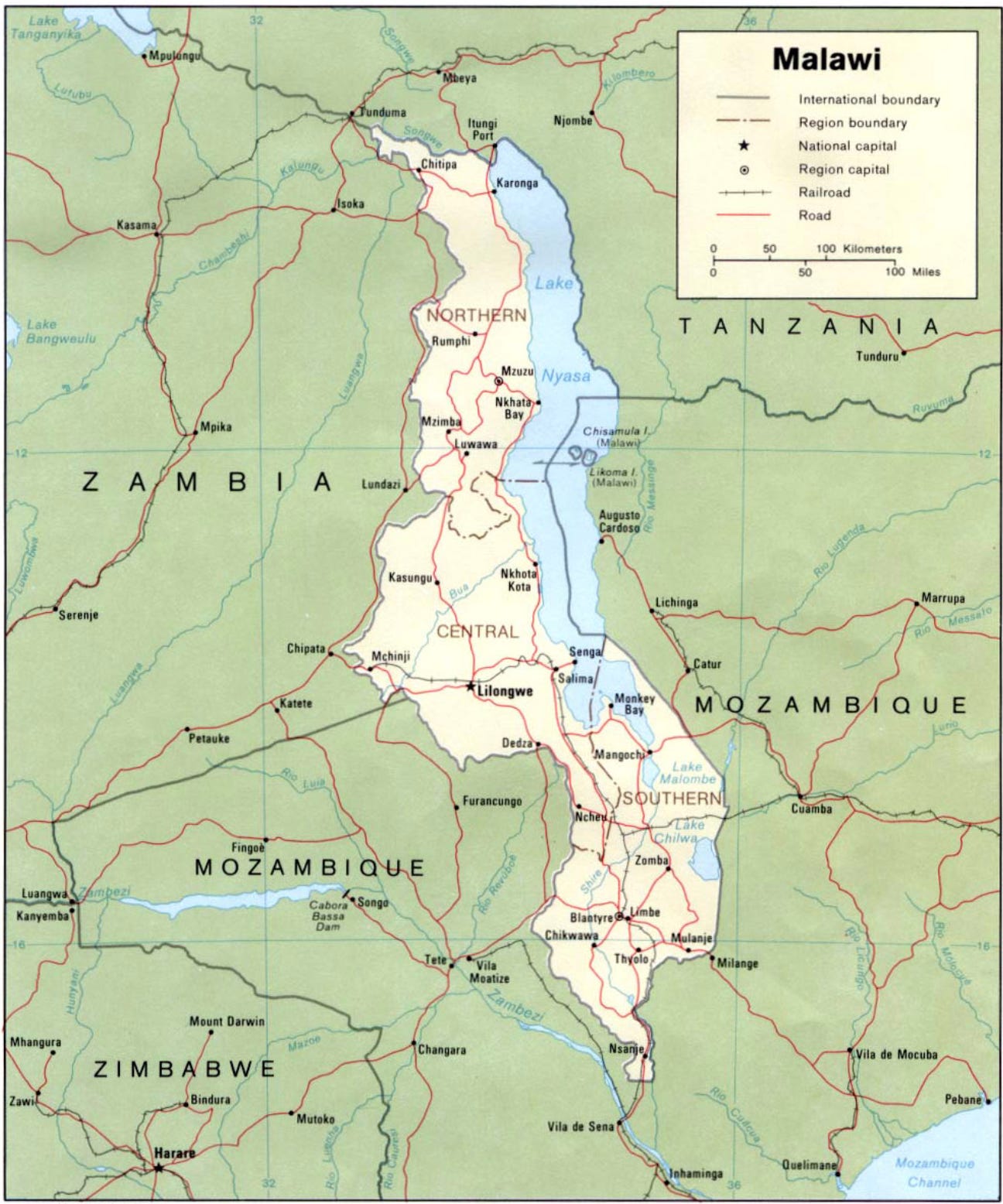

I’ve already talked about Uganda and Burma extensively in the last post, which you can read here. I’ll talk about another lesser known expulsion here — the one in Malawi in 1976.

As is common, the British had a big presence in East Africa. Which is why there were a lot of Indians in Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya among others. The British had also colonized Malawi. Similar to Uganda, the British recruited Punjabi and Gujarati traders3 to work on colonial projects including construction of railway lines. Traders and small business owners followed these workers to run shops and setup remote trading posts. And as is usual, the richest people in a society tend to be merchants.

In 1964, under Hastings Banda, Malawi won its independence from the British. Banda soon implemented Africanization, a policy intended to decolonialize Malawi. Indians in Malawi held British passports after independence and Banda asked them to either leave or give up their British passports if they wanted to stay.

This fits into the broader pattern that we’ll see in the newly independent African countries. The pattern goes something like this:

- The British colonize some African country.

- They bring over workers from other colonies to help with their colonial civil projects. India being the biggest colony, contributes the most indentured workers. To be fair though, there were a fair number of clerks and other civil workers brought over from India too.

- Due to selection effects, the Indians migrating to the colonial country often have high human capital. Plus, there are more immigrants following the initial wave as traders and businessmen.

- Indians become richer than the native population of the place. Understandably, that invites resentment from the ethnic majorities in the place. They’re seen as extensions of the colonial state.

- The British leave and grant independence.

- Newly independent country tries to force Africanization. That is just a fancy term for African decolonization. What is the most obvious, dominant symbol of colonization after the Europeans? The Indians! And the last nail in the coffin is that more often than not, they’re the richest minorities.

- Indians bristle at names like Victoria Terminus. They relocated the statues of colonial figures. Similarly, Africans also wanted to get rid of colonial symbols as a process of indigenization. One of the symbols were the rich Indians. And so the varying levels of anti-Indian sentiment started appearing.

The biggest proponent of this theory was Mahmood Mamdani4. He expounded his colonial intermediary theory where he says that even though this minority wasn’t the colonizer, they still reaped the benefits of colonization. Because of this, they should be considered as privileged in the colonial hierarchy.

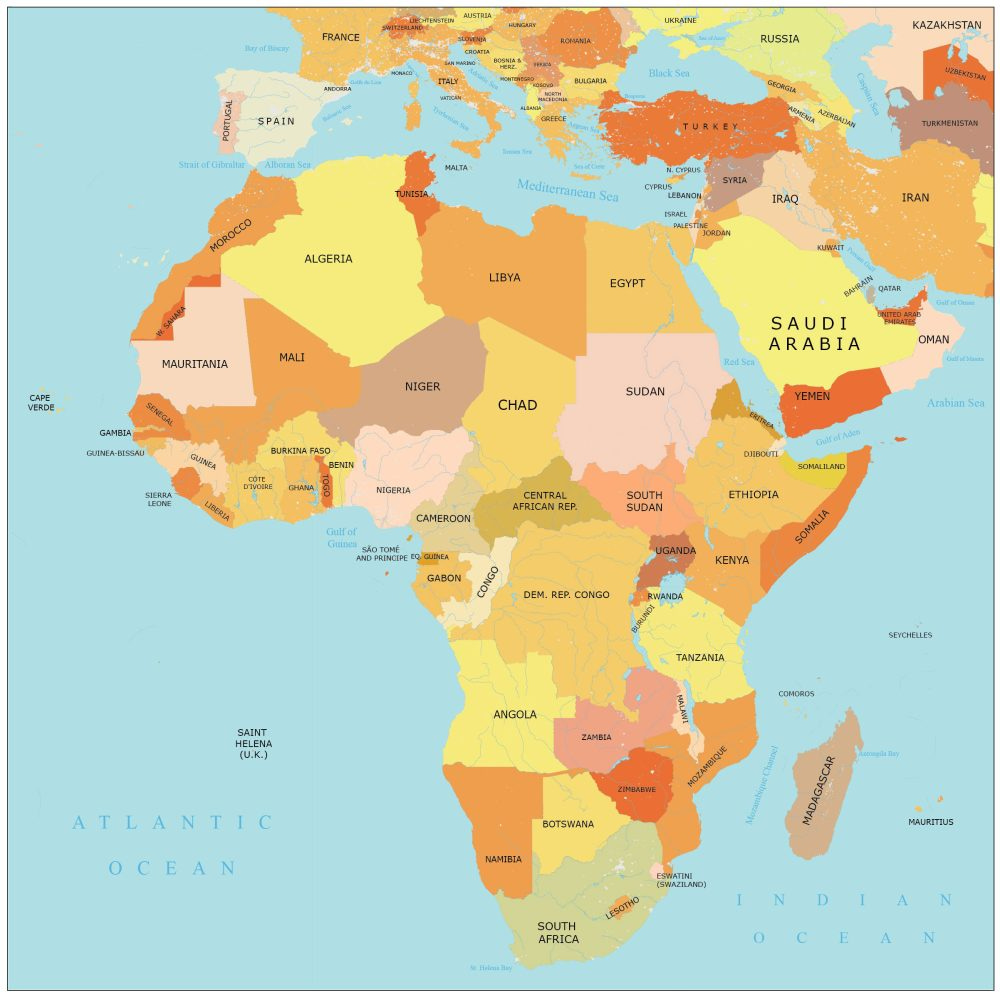

If you look at the map above, Indians faced the most hostility in Uganda. But strong anti-Indian sentiment persisted in Malawi, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa. The same pattern I’ve elucidated above applies to all of these countries. Most of these countries were part of British East Africa.

Zambianization happened in Zambia. In the 1960s and 1970s, Zambia wanted to reduce non-Zambian citizens in its economy and specially in the commercial class. Indians faced licensing restrictions for many businesses which pushed many to migrate again to the UK or Canada.

During the Mugabe period in Zimbabwe, Indians were often lumped into the category of foreign economic exploiters, but there wasn’t any mass persecution. There was general xenophobia and Indians were often blamed for price increases during its periods of hyperinflation.

In Tanzania, Indians were perceived as ethnic outsiders and that was a driver of socialism and economic restructuring by Julius Nyerere. Indians again left Tanzania for greener pastures which included the UK and Canada. Rishi Sunak, the erstwhile PM of the UK, was born in the UK but his parents migrated from Tanzania in the 1960s because of these policies.

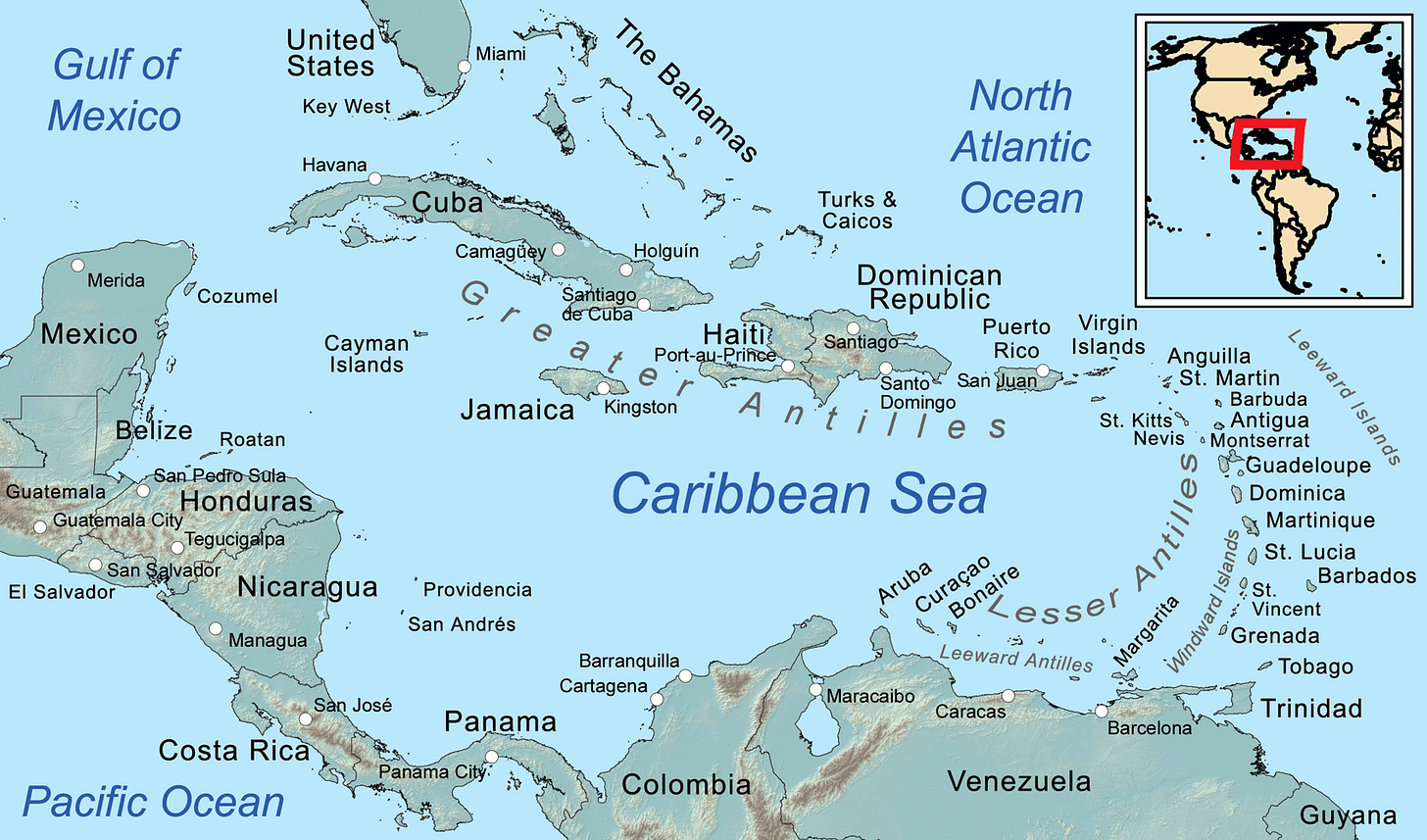

The Caribbeans are a set of small island states in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them lie somewhere between North America and South America. In the 1830s, the British abolished African slavery. As a result, they needed labor in sugar plantations. Many agrarian farmers facing lean years were recruited as indentured labor from the 1830s until the early 1900s. Many of them came from United Provinces (present-day Uttar Pradesh), Bihar and Bengal.

This led to a presence of Indians across all the Caribbean nations. That includes Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, Guyana, Mauritius, Grenada, St Kitts and Nevis, Suriname and many more. The pattern here is quite different from the one in Africa.

- After the end of slavery in the 1830s, Afro-Caribbeans expected higher wages and better working conditions. The Indians being brought in as indentured labor were seen as competitors that cut wages.

- Indians were often culturally separated from the natives. They maintained their religion and often maintained endogamy, preferring to marry within caste. In my estimate, this created a cultural separation between the native ethnicities and Indians.

- Because the populations in the Caribbean were small, and Indians were imported in large numbers, they quickly became either the plurality or the majority populations in many of these countries. They did remain a small minority in quite a few though, Jamaica being a good example.

- After Caribbean independence, they quickly became the politically and economically dominant population. The voting patterns were often ethnic voting, where ethnicities voted for politicians from their own ethnicities.

- As expected, this created resentment against Indians. Indians face various forms of political repression and riots. There aren’t any outright expulsions, but the environment becomes hostile enough that much of the populations leaves for other Western countries like Netherlands and Canada.

The interesting question here is why did Indians get rich if they didn’t arrive as the merchant class like in East African countries? The reasons primarily given are superior family and tribal ties within the Indian community. For example, Indians married within their community, tended to live in joint families rather than nuclear families and formed ethnic market clusters. Is this the whole explanation? Likely not. There are probably accidents of history that might have a non-significant role to play in this.

One good reason could simply be selection effects. In essence, immigration is often a high-agency choice. Those that immigrate are simply drawn from a pool of risk takers. It stands to reason that those traits are useful for earning and gathering wealth.

Post-independence, there were quite a few anti-Indian incidents.

- There were the Black Friday 1962 riots in Guyana where Indian shops were looted.

- The Wismar/McKenzie Massacre resulted in the murders and rapes of many Indo-Guyanese.

- In the 1950s, Indo-Trinidadans were targeted for intimidation during election times.

- Huge numbers of Indo-Surinamese migrated to Netherlands for fear of reprisals when it was evident that Suriname would get its independence in 1975. Political intimidation was a big threat.

Over time though, these ethnicities learnt to live with each other peacefully. Today most of the Indo-Caribbean communities forms a significant chunk of their countries’ populations. But there is some evidence to suggest that in these countries, the economic disparity between Afro-Caribbeans and Indo-Caribbeans is decreasing.

The diaspora history of Indians is quite interesting. What started off as an idle curiosity into an H-1B question evolved into something quite a bit more.

Indians have faced protests and political backlash in quite a few countries other than the ones mentioned above. Fiji and Indonesia have often had generic anti-foreign sentiment rather than specifically against Indians. In Singapore and Malaysia, Indians have been caught in the crossfire of anti-Chinese sentiment.

In the Western world, the backlash is more evident simply because of the global news cycle. The US is going through a particularly virulent phase of anti-Indian and more specifically anti-Hindu sentiment. Britain is grappling with hostile sentiments against Pakistan and there’s some spillover of that onto Indians. And there’s specific hostilities against Hindus in Canada primarily as a result of Canada ingratiating itself to Khalistanis.

While researching this article, I was disappointed by the lack of historical records kept by the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA). Ideally, I’d have expected a few paragraphs on how the Indian diaspora ended up in these small countries and microstates. But I had to hunt for information in footnotes and obscure journals. There’s a shocking absence of historical bookkeeping that’s within living memory.

To prevent this article from becoming excessively long, I decided to tackle only two broad categories of Indian diaspora – Caribbean and African. I’ll soon make a sequel that will talk about the final category of our Indian diaspora – the one in the West.

The Indic Prism is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

While MEA data does say that there’s one Indian-origin representative elected in Argentina, I haven’t been able to find any data on who that person is.

Coincidentally, the person elected in Zimbabwe is Modi — Rajesh Kumar Indukant Modi.

It is shameful that I had to hunt British archives for figuring out how exactly Indians ended up in Malawi.

Zohran Mamdani’s father.