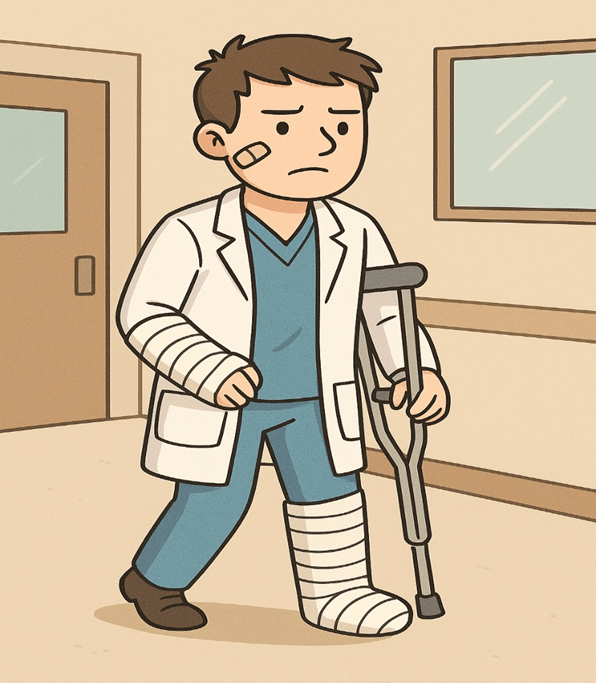

I joined Paediatric Surgery as a first-year resident three decades back. In my second year, I got married, which was the greatest and only excuse allowed—besides death or fleeing forever on the first available train to a distant place—for taking a break from the back-breaking, heart-stressing, mind-numbing, and emotionally crushing experience one endures in the hospital wards. There is a story about an overworked resident who jumped from the building; however, since he failed to die, he had to return the next day with plaster casts, crutches, and bandages for his ward duties. Anyway, that is how residency works. No human being in the history of humanity would have looked so forward to the idea of marriage.

Anyway, before marriage, my future in-laws visited me and saw the single, dreary hostel room. They asked me where the other rooms for their dear daughter were. I showed them the four corners of the room, each representing the kitchen, bedroom, study, and drawing room. An accompanying old man asked, “What does a paediatric surgeon do?” I winced at the gross ignorance. I slowly explained what paediatric surgery entails, but they appeared sceptical about the speciality. Given the numerous stories of fraudsters and conmen associated with big cities, I felt they almost suspected fraud.

After two decades of practice in a smaller town, I am still upset by the lack of knowledge about paediatric surgery in our society. It bothers me when people come to me to get their kids vaccinated or to talk about their kids’ coughs or fevers or rashes, or not eating or not sleeping. I want to hit their thick heads with my strongest fist. We have not been able to seep and soak into public consciousness as much as our more famous counterparts, like neurosurgeons, cardiac surgeons, plastic surgeons, or the urologists.

When we were a fledgling body, the general surgeons happily took away our meat; today, an array of sub-specialities, especially the organ specialists, cast their evil eyes, evil hands, evil minds, and evil hearts onto us. An average person likely associates obstetrics and gynaecology with deliveries, urology with stones, oncology with cancer, orthopaedics with fractures, plastic surgery with burns, cardiac surgery with bypass surgeries, and neurosurgery with head injuries. The filling of the blanks after the speciality is clear, easy, and straightforward. We deal with a wider variety of cases involving all organ systems, but when a layperson thinks of paediatric surgery, there is a quick zen state, where the mind dissolves. The average person is simply lost. However, the irony is that the diversity of paediatric surgery is huge—so incredibly huge that it is not the “right hand not knowing what the left hand does”, but the “right middle finger not knowing what the right index finger does”.

Paediatric surgeons work with most organ systems, but they focus on a specific age group that ranges from birth to 18 years, as we define it (or 12 years according to adult surgeons – for obvious reasons). We work on gross and unbelievable misadventures of nature where multiple stages are involved. The results are sometimes neither perfect nor optimal for the quality of life. However, with really long-term outcome measures, many patients stick to the operating surgeon for their own lifetimes or for the lifetime of the surgeon, whichever ends first. Some experiences can be disconcerting and depressing, but thankfully most patients return for follow-up visits without stones in their hands to throw at the surgeon. When a newborn who was operated on the first day of life returns twenty years later, or even later with their children, the paediatric surgeon experiences some of the most rewarding moments that make medicine worthwhile. The reality of ageing also becomes evident, yet it’s a minor cost to bear.

A key aspect of paediatric surgery involves newborns born with various malformations affecting the food pipe, windpipe, intestines, back passage, kidneys, liver, lungs, brain, or spine, either in isolation or in various combinations that may include blockages, absences, abnormal growths, and so forth. Caring for these newborns necessitates intricate and complex surgeries, as well as a lifetime of ongoing care. The decline in the number of newborns or neonates with these congenital malformations—perhaps the core definition of a paediatric surgeon’s role—presents a dilemma that exists in a grey ethical zone.

When I began my practice, neonates constituted nearly 30% of my workload; today, that figure has dropped to less than 5%. I once went to purchase a long and strong stick to beat my colleague and competitor in town, believing he was taking all my neonatal cases. To my surprise, I discovered that he was purchasing even stronger sticks at the same shop for using them against me. We resolved the misunderstanding, hugged, and contemplated the situation. Where are all the neonates going? A significant ethical question is whether doctors should feel happy or sad when the disease burden in society diminishes. There exists a technological vision, likely to materialise in a few centuries, suggesting that doctors may eventually become obsolete. However, why should neonatal surgeons be the first to face this prospect?

The advances in technology, extremely anxious obstetricians, and a societal drive for a “perfect” baby have increased selective terminations and a resultant reduction in the number of children born with congenital anomalies. The foetus under intense study is subjected to severe pressures to survive as the range of “acceptable normality” is shrinking and the range of “unacceptable abnormality” is ever-increasing. Thus, the foetus is almost assumed to be abnormal until proven otherwise. As our radiologists, perinatal pathologists, geneticists, and foetal medicine specialists continue to dig deeper into the foetus on a daily basis, they are increasingly collaborating to prevent paediatric surgeons from gaining any fame or money. As we grow poorer, the only consoling ray of hope is a golden future, where one day we can perhaps predict which of the foetuses will become lawyers, medical insurance providers, journalists of any kind, or politicians. Termination can proceed rapidly in such cases.

Anyway, I once took my mother to a busy cardiologist for her health check-up. She saw the thousand patients outside his consultation room and told me, “Dear boy, why did you not take up cardiology?” I winced, recalling my gruelling training days. Then, I took her to a busy ophthalmologist for a check-up. There were ten thousand people waiting outside his room. Thoroughly impressed, she again asked me why I had not become an ophthalmologist. I winced again and told her that paediatric surgeons were also important in the cosmic scheme of things. She appeared doubtful and concluded firmly that I had made the greatest mistake of my life.

The redeeming feature came when she visited my clinic. She saw many patients waiting outside my clinic and a huge bubble of activity. She was filled with pride, but I never had the courage to inform her that it is necessary to divide the number of people waiting outside a paediatric surgeon’s clinic by at least four. Each patient is accompanied by a diverse group of parents, grandparents, relatives, and the most extreme hooligans. As a speciality, collectively, we like to believe that we do our work silently without much advertisement. However, despite all the problems, most paediatric surgeons would perhaps opt for the same specialisation if given the option to take a different path. At least I do. It is only somewhat disheartening when society (and my dearest late mother) feels that it should have been on a different trajectory.

My better half, a non-medico, luckily remains proud of her husband (hopefully) and his chosen field. In the early years of her marriage, she eagerly scanned the newspaper’s appointment pages, only to be thoroughly disappointed by the glaring absence of advertisements for paediatric surgeons. Today, she continues to peruse the newspapers with that same enthusiasm, yet her disappointment remains unchanged. Her primary complaint persists: when will the world, hospitals, and medical colleges truly ask for paediatric surgeons?

But I am happy to be a paediatric surgeon. I like to think of our tribe as the chosen ones by the Divine for our good Karma. The smiles of the children can inspire us to carry on indefinitely despite all the challenges, heartbreaks, uncertain results, less money, or fame. Whether rooted in genuine pride, false patting of our backs, or mere hubris, we consider ourselves to be the best of the best, regardless of the ignorance surrounding our speciality. Go for a walk, fellow doctors!